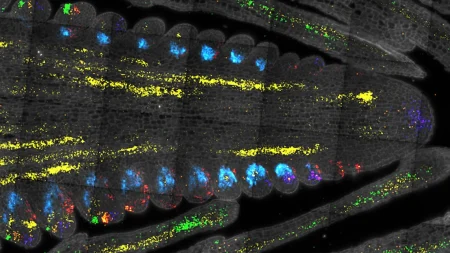

A recent study led by the University at Buffalo and the Jackson Laboratory has unveiled how the duplication of the salivary amylase gene (AMY1) may have played a significant role in human adaptation to starchy foods, dating back over 800,000 years. AMY1 is responsible for breaking down starch in the mouth and affecting how effectively humans digest starchy foods like bread and pasta. The study highlights that individuals with more copies of the gene can produce more amylase, which aids in the digestion of starch. The research utilized advanced sequencing methods to trace the evolution of AMY1 duplications in present-day humans.

Through the analysis of ancient human genomes, including samples dating back thousands of years, researchers discovered that hunter-gatherers and even Neanderthals already possessed multiple AMY1 gene copies. This suggests that the gene may have duplicated over 800,000 years ago, long before the split between humans and Neanderthals. The initial duplications of the gene set the stage for genetic variation in the amylase region, allowing humans to adapt to changing diets as starch consumption increased with new technologies and lifestyles. This genetic variation helped humans adapt to varied environments, particularly those with starch-rich diets.

The initial duplication of the AMY1 gene served as a catalyst for genetic opportunities that shaped our species as they spread across different environments. The flexibility of AMY1 copy numbers provided an advantage for adapting to new diets, particularly those rich in starch. The research suggests that the gene locus became unstable following the initial duplication, creating new variations in AMY1 copy numbers. This variability allowed individuals to range from having three to nine copies of the gene, influencing their ability to digest starch effectively.

Agriculture significantly impacted AMY1 variation, with European farmers experiencing a surge in the average number of gene copies over the past 4,000 years due to their starch-rich diets. This increase in copy numbers was likely beneficial in digesting starch efficiently and having more offspring, leading to better evolutionary outcomes for individuals with higher AMY1 copy numbers. The findings align with previous research showing that humans in Europe expanded their average AMY1 copies from four to seven over the last 12,000 years. This genetic variation presents an exciting opportunity for further exploration into its impact on metabolic health, nutrition, and understanding the mechanisms involved in starch digestion and glucose metabolism.

The study emphasizes that the number of AMY1 gene copies likely influenced the evolutionary success of individuals, affecting their ability to digest starch and adapt to changing diets over time. By uncovering the impact of AMY1 genetic variation on human evolution, researchers hope to gain critical insights into genetics, nutrition, and health. Future research may provide a deeper understanding of the effects and timing of selection related to AMY1 copy numbers, shedding light on the role of genetic variations in shaping human metabolic health. The collaboration between various research institutions and the support of funding agencies have enabled the study to shed light on the ancient origins and evolutionary implications of AMY1 gene duplications in humans.