Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs

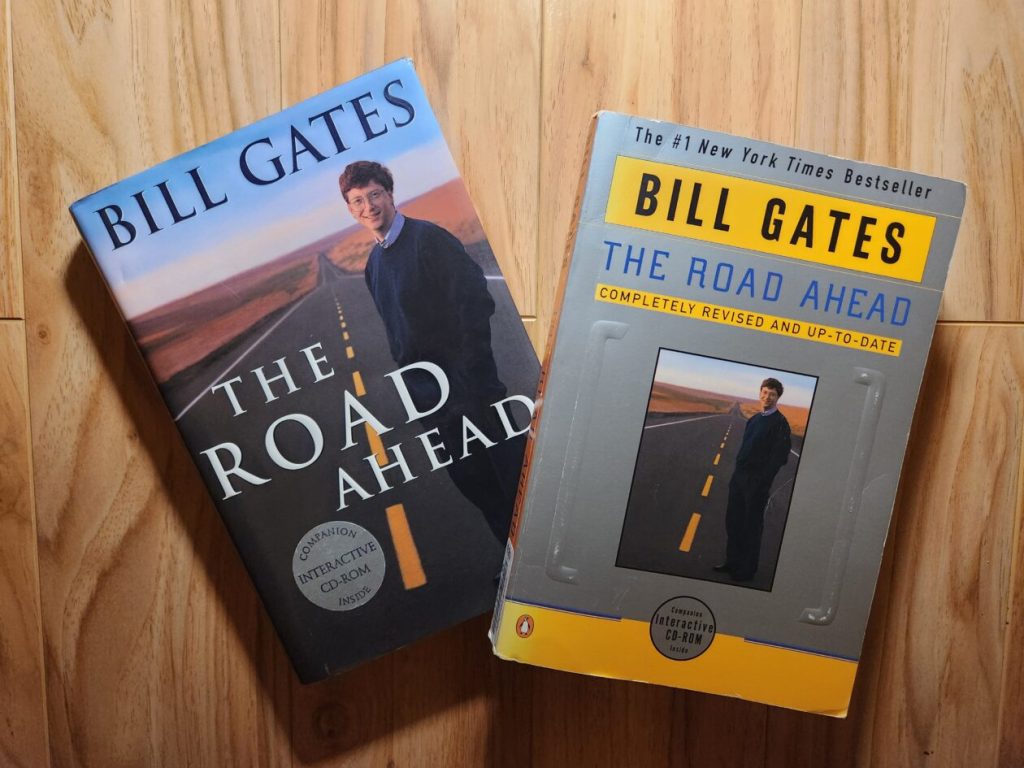

The 1995 original hardback and 1996 paperback editions of The Road Ahead, by Bill Gates, Peter Rinearson, and Nathan Myhrvold. (GeekWire Photo / Todd Bishop)

Editor’s Note: Microsoft @ 50 is a year-long GeekWire project exploring the tech giant’s past, present, and future, recognizing its 50th anniversary in 2025. Learn more and register here for our special Microsoft @ 50 event, March 20, 2025, in Seattle.

Bill Gates knew he would be judged.

His first book, The Road Ahead, published during the rapid rise of the internet in the mid-1990s, was packed with so many predictions that some were destined to be wildly off the mark.

“This is meant to be a serious book, although ten years from now it may not appear that way,” the Microsoft co-founder wrote in the foreword. “What I’ve said that turned out to be right will be considered obvious, and what was wrong will be humorous.”

Thirty years later, some of the predictions do elicit a laugh, or at least a head-scratch. Come on, people of 2025, you’re not glued to a livestream of your floral arrangement being prepared, or using the internet to see which vending machine has your favorite soda in stock?

But those are the exceptions.

For this fourth installment in our Microsoft @ 50 series, GeekWire revisited Gates’ classic book, with the benefit of three decades of hindsight.

We found in its pages a vision for technology that was essentially on the mark — foreseeing pervasive access to information, the rise of smart devices, and the central role of the internet in business, education, and the home. We also discovered striking parallels and insights relevant to the AI revolution the world is experiencing today.

Most of the misses are about more about human behavior than about technology. After all, scenarios such as those above are possible today, even if there’s no real demand for them.

Gates’ vision for the future “has proven to be remarkably accurate, painted broadly,” said Peter Rinearson, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, writer, entrepreneur, and former Microsoft VP, who co-authored The Road Ahead with Gates and former Microsoft CTO Nathan Myhrvold.

At its core, the book is about a computing pioneer foreseeing another revolution.

Gates “had foreseen early on that computing power would become cheap and ubiquitous,” Rinearson said in a recent interview. “By the early 90s, this was already becoming true. Computing was becoming effectively free. Bill could see that communications was on the way to becoming free or nearly free, too … and this was going to have profound impacts on the world.”

“Of course,” he said, “this has happened.”

But any retrospective assessment of the book needs to distinguish between the 1995 hardback and the 1996 paperback versions — because they were very different. As Rinearson recalled, “The word ‘internet’ only showed up a couple of times in the hardback edition.”

Instead, the focus was on the “information highway.” When the book was first written, Gates and Microsoft were betting on Microsoft’s MSN to serve as the onramp and backbone of that highway. By the time the first edition went to press, it was clear the broader internet would prevail. Microsoft was already reorienting itself for this reality when the book came out.

This mirrors a common criticism of Microsoft products. The company has often struggled to hit the mark the first time, relying on follow-up releases to fix Version 1.0 bugs and oversights. Windows, Office, Internet Explorer and others would follow the same pattern.

But it also illustrates a major parallel between then and now in the tech world. The internet was gaining traction so quickly at the time — much as AI has in the past two years — that Gates and Rinearson felt compelled to completely revamp the book for the paperback release.

They revisited every sentence, rewrote entire chapters, and added 20,000 words in all — an extraordinary overhaul for a paperback edition just one year after a hardback’s release.

Foreseeing the tech of today

The global reach of The Road Ahead. (Photo courtesy of Peter Rinearson)

Even with the rewrite, the overall vision remained much the same. And many of the predictions ended up so close to reality that it’s easy to name their modern equivalents.

“Kids in school will be able to produce their own albums or movies and use the net to make them available to friends and family.” (YouTube, TikTok, etc.)

“Your misplaced or stolen camera will send you a message telling you exactly where it is, even if it’s in a different city.” (Location-aware devices and tracking apps.)

“If you’re watching a video of Top Gun and think that Tom Cruise’s aviator sunglasses look really cool, you’ll be able to pause the movie and … buy them on the spot.” (Shoppable product placements. Bonus: Cruise and Top Gun are still around.)

A video camera will “let the PC recognize who is using it so that the PC can better anticipate the person’s needs or carry out policies.” (Biometric authentication.)

It goes on and on, for more than 300 pages, including changes in the workplace that sound like they’re ripped from a modern-day report on trends in U.S. commercial real estate.

“The number of offices a company needs might be reduced,” reads one passage predicting the rise of remote work along with the internet and digital technologies. “A single office or cubicle could serve several people whose inside hours were staggered or irregular.”

Other predictions were so far ahead of their time that they are only now just unfolding. The biggest example: a vision for software agents that tailor their actions to a user’s needs.

“An agent will know how to help you partly because the computer will remember your past activities,” Gates predicted, although he called this “softer software” rather than artificial intelligence. “It will note patterns of use that will help it work more effectively with you.”

This is the hot trend in AI in 2025. Microsoft, Salesforce and many others are deploying agents for businesses, and aiming to make AI a true personal assistant by allowing it to remember. Mustafa Suleyman, Microsoft’s CEO of AI, calls long-term memory a key next step for AI, and Microsoft’s Windows Recall feature aims to give the PC a photographic memory.

The book did use the term “artificial intelligence” in other areas, including one passage where Gates was uncharacteristically conservative about the timeline for the technology.

“Although I believe that eventually there will be programs that will recreate some elements of human intelligence, I don’t think it’s likely to happen in my lifetime,” he wrote.

“For decades computer scientists studying artificial intelligence have been trying to develop a computer with human understanding and common sense,” he wrote, adding later, “So far every prediction about major advances in artificial intelligence has proved to be overly optimistic.”

Fast forward 30 years, and Gates calls AI “the biggest technological advance in my lifetime.”

A diagram in The Road Ahead foreseeing the wallet PC. (Click to enlarge.)

And then there was the most bittersweet prediction of all: the “wallet PC.”

A dozen years before the debut of the iPhone, the Microsoft co-founder foresaw something that sounded very similar to the devices we carry around in our pockets today — a portable, pocket-sized computer, roughly the size of a wallet, that would combine many features and functions, such as keys, credit cards, GPS directions, a camera, and more.

“It will display messages and schedules and also let you read or send electronic mail and faxes, monitor weather and stock reports, and play both simple and sophisticated games,” the book predicted. “At a meeting, you might take notes, check your appointments, browse information if you’re bored, or choose from among thousands of easy-to-call-up photos of your kids.”

But the very name of this concept, the wallet PC, foreshadowed one of Microsoft’s biggest stumbling blocks as it later developed and brought this technology to market. Rather than inventing a new category of device, Microsoft initially tried, in effect, to miniaturize the PC.

By the time the company came around to a different approach, Apple’s iOS and Google’s Android were on their way to dominating the smartphone market.

“Was the vision of the wallet PC correct? Yes,” Rinearson said. “We call it a phone, not a computer. It doesn’t run the Windows operating system. It’s not a PC in that sense. But his vision of where we were going was spot on.”

A lens on the past

But there was something else that struck Rinearson when he revisited the book recently in preparation to talk with GeekWire for this piece: Readers of the book in the 1990s may have marveled at the future it painted, but in 2025, it’s a reminder of how far we’ve come.

Here’s a good example, from Chapter 4, on Information Appliances and Applications: “Instead of having to remember the channel of a TV program, you’ll have the ability to use a graphical menu that will let you select what you want by pointing to an easy-to-understand image.”

Yes, there was a time when we had to remember the channel — not browse a row of icons or speak to a remote. In that way, this book of the future has become a window into the past.

Peter Rinearson.

“It’s like this bridge,” Rinearson said. “We went through this divide, this watershed moment in human history. … This book came out right when this was happening, and so you can use it to look either forward or backwards.”

The book pointed to many of the pitfalls of the impending information and communications revolution, including the impacts on security, privacy, jobs, social isolation, and the digital divide where individuals and communities without access to technology would be left behind.

But looking back, Rinearson said he was struck by the downsides they missed.

“We talked about how great it was going to be when anyone could reach an audience. … You have the potential to reach anyone in the world if you have a compelling enough message,” he said. “I don’t think we thought enough about how that might be corrosive or negative.”

Rinearson quoted a line from the final chapter of the book, “Critical Issues,” which explored upsides and challenges of the emerging digital world: “The network will draw us together, if that’s what we choose, or let us scatter ourselves into a million mediated communities.”

Reflecting on that line, Rinearson said recently, “You can see in that simple sentence that Bill understood the potential for polarization and fragmentation, but I don’t think either of us foresaw how many people would choose to scatter into their own realities.”

Ironically, in recent years, Gates himself has felt the sting of disinformation, saying he has to maintain a sense of humor when he hears conspiracy theories about vaccines and microchips.

After reading the book and hearing Gates at a New York event, Frank Rich of The New York Times wrote in a December 1995 column that the negative implications of Gates’ vision of the future — in areas including privacy, job loss, and social division — should serve as a wake-up call for the world.

“Bill Gates doesn’t offer solutions for these troubling issues,” Rich wrote. “He merely raises them, professes optimism, and invites the rest of us to cope as he returns to making money. Who will lead the debate? … Most mass-media reportage on computers is turned over to specialists, whose assignment is to chart the changing fortunes of technology corporations and products rather than look at their long-term impact.”

The columnist concluded the piece, “Even David Letterman boasted to Mr. Gates this week of how little he knows about computers. If he and the millions of Americans like him were to actually read ‘The Road Ahead,’ they would discover that digital ignorance offers no protection from a future that will arrive whether we want it to or not.”

Of course, The Road Ahead was widely read, quickly becoming the best-selling nonfiction book in the United States, and ultimately appearing in numerous international editions.

The companion CD-ROM also received widespread attention, although in a failure of backward compatibility, GeekWire’s attempts to get it to play on a Windows 11 PC were unsuccessful.

Fortunately, as with most things these days, there’s a YouTube video for that, too.

Many reviews of the book in the mainstream press were laudatory, praising Gates for his ability to make the subject accessible to a broad audience. Rinearson recalled that Gates thought of his mother, Mary Gates, as representing the audience for the book. She was an accomplished community organizer and non-profit leader who wasn’t deeply immersed in technology.

In that way, the book was a success, even if it was criticized in the trade press and some corners of the industry for stating things that tech insiders considered obvious at the time.

“Bill and Nathan together certainly had the capacity to write a book that would be so dense and sophisticated that these tech journalists would’ve been lost in it, and would’ve really had to work their way through it, but that wasn’t the book Bill wanted to write,” Rinearson said.

Myhrvold’s contributions as a co-author shouldn’t be overlooked, he added, describing the former Microsoft CTO’s memos and contributions as “highly influential” in the process.

A revolution of intelligence

What would The Road Ahead look like if written in 2025? As a ghostwriter, Rinearson said he would defer to Gates on this question. But much as computing and communications were revolutionized in the past, he said, it’s clear that the same is now happening to intelligence.

“We’re now in a position to bring massive intelligence to bear on problems at relatively cheap prices,” Rinearson said. “This has never happened before. Quantum computing and AI will go hand in hand, and this will be incredibly disruptive in positive and negative ways.”

At the beginning of “The Road Ahead, Gates tried to set expectations for readers, explaining that he drew on his own history and that of the technology industry to inform the book, but cautioning that “anyone expecting an autobiography or an account of what it’s like to have been as lucky as I have been will be disappointed.”

He added, “When I’ve retired, I might get around to writing that book.”

That prediction was accurate, too.

Now approaching his 70th birthday, Gates will release a new memoir, Source Code: My Beginnings, in early February, focusing on his childhood and Microsoft’s early years, as the first in a planned trilogy of books about his life.

Coming next month: Bill Gates on Microsoft, AI, and the Road Ahead from here.

Previously in GeekWire’s Microsoft @ 50 series