Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs Encouraging bilingualism at home can have many cognitive benefits, which may be particularly helpful to kids with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), new research from the University of Miami College of Arts and Sciences indicates.

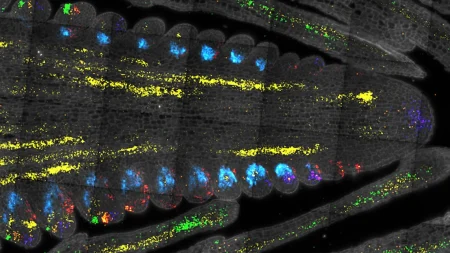

A team of researchers led by Celia Romero, a graduate student in clinical psychology, along with associate professor Lynn Perry, professor Michael Alessandri, and former University professor Lucina Uddin, explored the role of bilingualism in 112 children, including typically developing children and children with autism, between the ages of 7 to 12 years old. Overall, they found that children who spoke two or more languages often had stronger executive functioning skills. This means they are able to control impulses and to switch between different tasks more easily than children who only spoke one language.

“We discovered that multilingualism is associated with improvements in executive function, which in turn is associated with improvements in autism symptoms,” Perry said. “There were hints of this in the literature before, but it was exciting to see how far reaching those differences were in this research.”

Published in the journal Autism Research, the results are significant because executive functioning skills are a key challenge for children on the spectrum but are important for all kids to thrive in school and later in the workplace. Yet, the team found the benefits of speaking more than one language were not limited to children with autism.

Key features of autism include social communication difficulties and restrictive and repetitive behaviors, as well as difficulty with executive function skills. These are mental processes that help us plan, focus, remember instructions, and manage multiple tasks effectively. While executive function skills develop and improve across the lifespan, individuals with autism often struggle with executive functioning, impacting their ability to manage daily tasks and adapt to new situations.

The study also looked at the impact of multilingualism on core symptoms of autism, including perspective taking, restricted and repetitive behaviors, and social communication.

“We also found that multilingual children have enhanced perspective taking skills, or the ability to understand someone else’s thoughts or point of view,” Romero added.

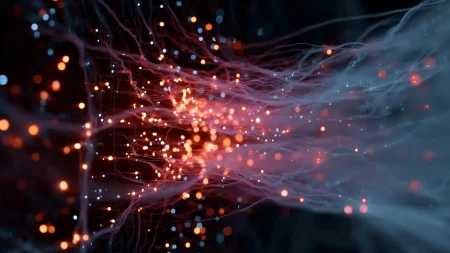

An idea called joint activation from the field of neuroscience can help explain the results. Prior research suggests that the bilingual brain has two languages constantly active and competing. As a result, the daily experience of shifting between these languages is associated with enhanced executive control. This concept is also known as the “bilingual advantage” and is a topic of much debate.

“If you have to juggle two languages, you have to suppress one in order to use the other. That’s the idea, that inhibition — or the ability to stop yourself from doing something — might be bolstered by knowing two languages,” said Uddin, now a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, and director of the Brain Connectivity and Cognition Laboratory.

Romero realized she wanted to explore this topic while working in Uddin’s neuroscience lab on campus that was doing brain imaging research on children with autism. She noticed that some bilingual families did not speak to their child in their native language because they thought it may be too challenging and harmful for their child to learn more than one language.

“I started investigating this to let families know there’s no detriment for their child to learn another language, whether or not they have a neurodevelopmental disorder,” she said. “We know this through research, but often it takes time to translate that to families, so I hope this study helps address that.”

In his work as executive director of the University’s Center for Autism and Related Disabilities, Alessandri said this question often comes up with parents.

“It is wonderful to have sound research supporting our general recommendation to not restrict language exposures to children in multilingual homes,” Alessandri said. “This will surely bring a sense of relief to many of our families living with loved ones with autism.”

Romero and Perry are now doing further research with preschool children to see if bilingualism also has an impact on kids’ peer interactions, which are crucial for children’s social and cognitive development. And at UCLA, Uddin is currently conducting a large follow-up study to further investigate the impact of multilingualism on brain and cognitive development in children with autism.