Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs Even cells experience peer pressure.

Scientists have long studied the ins and outs of cancer cells to learn more about the disease, but they’re increasingly finding that noncancerous cells near the cancer cells exert a powerful influence over a tumor’s trajectory.

“Not all cells in a tumor are cancer cells — they’re not even always the most dominant cell type,” said Sylvia Plevritis, PhD, chair of Stanford Medicine’s department of biomedical data science. “There are many other cell types that support tumors.”

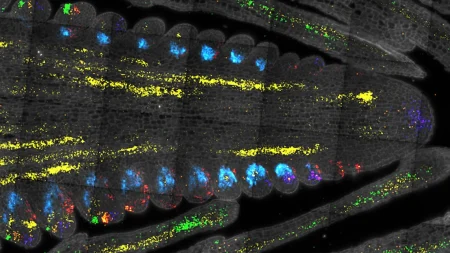

To better capture the whole picture of cells’ locations and interactions, Plevritis and a team of researchers have developed something that they call the “colocatome,” (pronounced co-locate-ome). Modeled after the nomenclature that describes other classes of molecules and facets of human biology (collective information about genes is called the genome; proteins, the proteome; metabolites, the metabolome, etc.) the colocatome documents the details of malignant cells on their neighbors — what those cells are and how many of them are present.

“We’ve been studying cancer cells for so long, but the picture is still incomplete,” said Gina Bouchard, PhD, instructor of biomedical data science. “Understanding tumor biology is not only about cancer cells; there’s a whole ecosystem that needs to be studied. Cancer cells need help to survive, to resist, to thrive and even sometimes to die.”

A study describing the findings was published in Nature Communications last month. Bouchard is the lead author, and Plevritis is the senior author.

Mapping influence

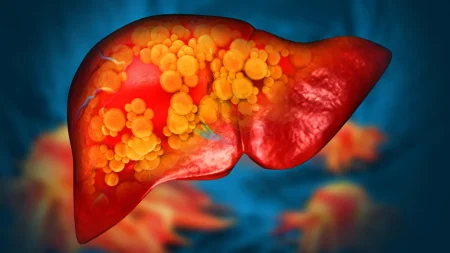

Cancer cells are surprisingly dependent on their surroundings. Depending on the location, type and quantity of noncancerous cells surrounding the tumor, the cells’ behavior can change, whether through faster growth, decreased susceptibility to drugs or heightened cell metabolism.

“The questions we’re asking are very simple. We want to know who the neighbors are for each cell. Who likes whom? Who doesn’t like whom? It’s all about which cells tend to be together, and which ones are rarely found together,” Bouchard said. Cells that attract each other are described as “colocalizing” while those that seem to repel each other form “anti-colocalizations.” Those colocalizations are then linked to the state of the cancer — aggressive, resistant, susceptible to drugs — and logged in the colocatome.

The team developed experimental models of lung cancer in the lab, then used artificial intelligence to analyze them, identifying noncancerous cells and how they organized within and around the tumor cells. They then compared the colocalizations with those from patient tumor biopsies. After mapping hundreds of cell configurations, they confirmed that the majority of colocalizations in the primary patient tumors are observed in the experimental models. (That overlap is key, said Bouchard. It means that the models are a valuable and accurate representation of what’s happening in someone who has lung cancer.)

Past research by Plevritis and others showed strong interactions between fibroblasts and cancer cells, but exactly how fibroblasts interact with cancer cells is unclear. In an experiment, Plevritis showed that lung cancer cells die when doused with a type of anti-tumor drug that stunts cell growth. But throw fibroblasts into the mix, and the entire landscape changes — literally. Plevritis mapped the treated tumor models and saw that post-treatment, the cancer cells and fibroblasts were generally left intact in the same amount. But they had rearranged themselves.

“That spatial reorganization appears to have given rise to drug-resistance,” said Plevritis, the William M. Hume Professor in the School of Medicine. “It was like changing the furniture in the room, then finding the exits are blocked.”

Chasing new leads

As the team continues to log spatial maps of treated and untreated tumors, they hope to unlock more configurations that help clue doctors in on why some cancers persist after treatment. Ideally, the researchers said, the colocatome could provide information that guides treatment of patient’s cancer: If a specific colocalization confers resistance to a common drug, for instance, physicians can search for another that might have a better chance of working. They also hope the colocalization maps will generate testable hypotheses to describe aspects of cancer biology that remain unclear.

As they collect more data, the team plans to employ AI to identify specific spatial motifs and create catalogs of maps that correspond to different cell states for a variety of cancers. “Then we can begin to see whether certain spatial motifs are shared between cancer types, regardless of where they originate in the body. That could reveal universal rules of tumor behavior and guide the design of more broadly effective treatments,” Plevritis said. “That’s something I’m really excited about.”

A researcher from the University of Oxford contributed to this research.

This study was funded by the National Institute of Health (grants R25CA180993, U54CA274511 and K99CA255586) and Les Fonds de Recherche du Québec.

Stanford’s Department of Biomedical Data Sciences also supported the work.