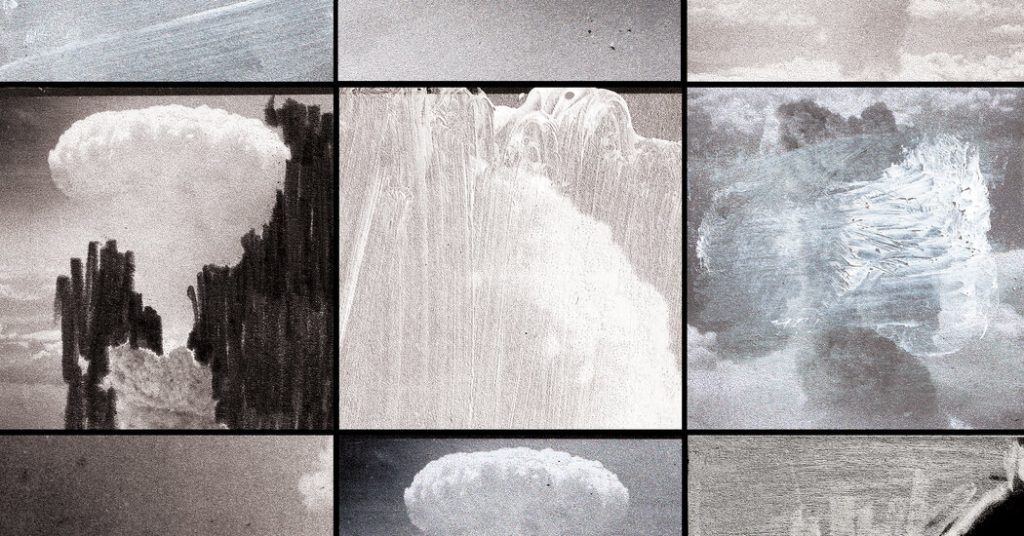

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs President Trump’s deference to Russia, his unprecedented rebuke of Volodymyr Zelensky and his no-holds-barred approach in prodding European partners to spend more on their military budgets are having an unintended impact among America’s longtime allies: a possible nuclear free-for-all.In recent days, emergency meetings have been convened in foreign capitals, and alarming public statements have been delivered by Poland, Germany and South Korea about their consideration of acquiring nuclear weapons. It’s a remarkable turn of events that portends a new nuclear landscape.America’s European and Asian allies haven’t contemplated their nuclear futures this earnestly — and openly — since the dawn of the atomic age. For decades, they have relied on Washington’s policy of extended deterrence, which, by dint of treaties, promises more than 30 allies safety under America’s nuclear umbrella in exchange for forgoing the development of their own arsenals. The nations don’t need nuclear weapons to deter adversaries from a nuclear attack, according to the policy, because the United States guarantees to strike back on its allies’ behalf.But confidence in that longstanding arrangement began to break down after allies watched Mr. Trump pull weapons and intelligence support from Ukraine last week in its war with Russia. It weakened further when he again upbraided NATO allies for not boosting their military spending, warning the other 31 alliance members not to count on the United States to defend them if they fail to meet their obligation to spend 2 percent or more of their gross domestic product on defense.Tremors from the president’s actions were promptly felt across the Atlantic. Prime Minister Donald Tusk of Poland warned Friday about the “profound change of American geopolitics,” which put his country, and Ukraine, in an “objectively more difficult situation.” Poland must now consider reaching “for opportunities related to nuclear weapons,” he said in a speech to the Polish Parliament. “This is a serious race: a race for security, not for war.”Friedrich Merz, who is expected to become Germany’s next chancellor, expressed a similar sentiment last Sunday when he told a national broadcaster that Berlin should discuss a nuclear sharing agreement with France and Britain, which, unlike Germany, are nuclear powers. The two nations have far fewer weapons than the United States’ and Russia’s stockpiles of more than 5,000 warheads, but they do have sizable arsenals, with Britain at 225 weapons and France at 290.President Emmanuel Macron of France said his country was willing to consider extending the protection offered by its arsenal to European allies that are interested. It remains an open question whether and how that would work, but it’s an interesting idea. While Britain’s nuclear arsenal depends on U.S. technical input for its ballistic missile systems, France’s does not. “Our nuclear deterrent protects us. It is comprehensive, sovereign and French through and through,” Mr. Macron said last Wednesday in a televised address.France’s arsenal has been that way since the 1960s, when then-President Charles de Gaulle started a nuclear program against the wishes of Washington. Although he was offered a place under the U.S. nuclear umbrella, he questioned America’s commitment to protecting Europe: Would the United States risk a nuclear attack on Washington if Paris was hit? He surmised it might not, calculating that American politicians’ interests would not always align with a European nation’s concerns.That view proved prophetic over the past few weeks as Mr. Trump has disparaged Ukraine’s attempts at defending itself against unprovoked Russian military aggression. The world watched as Mr. Zelensky was berated in front of television cameras at a White House meeting on Feb. 28 for being “disrespectful” and risking “World War III.” The extraordinary dressing down of a nominal ally at war, coupled with the subsequent White House decision to pause military aid and intelligence support for Ukrainian forces, roused allied leaders into thinking: Can we still rely on the United States to come to our defense in a struggle?Signaling their misgivings about the answer to that question, European leaders last week discussed a collective military spending plan, totaling about $160 billion, for missile defense, weapons systems and other military hardware. While the decision to take the Europeans’ conventional military capabilities into their own hands is welcome — and perhaps overdue — the possibility of nuclear expansion is unnerving.The goal of every American president since Harry Truman has been to limit the spread of nuclear arms rather than encourage their development. During the Cold War, the United States deployed nuclear weapons in nations around the world in the event of an all-out war with Moscow, as well as to reassure allies of America’s commitment to their defense. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, most of these weapons were removed from those nations. Those that remained became more symbolic of a lasting partnership and a visceral extension of the nuclear umbrella than a practical tool of war. Today, roughly 100 nuclear bombs are deployed in five NATO nations: the Netherlands, Germany, Italy, Belgium and Turkey.Extended deterrence has been recognized by Democratic and Republican presidents as beneficial to the United States, in part because it tightens military alliances. But perhaps more important, it has discouraged other nations from expending the time, money and energy of going nuclear and creating a more destabilized world.The policy has worked surprisingly well. Just nine nations possess nuclear arsenals, despite many more having the technical ability to build one. Public polls in South Korea, for instance, have shown for a decade that more than half the population wants homegrown nuclear weapons. North Korea’s fast-growing nuclear arsenal and routine threats by its leader, Kim Jong-un, to use them have made South Koreans uneasy about the arrangement with the United States.And while South Korea’s government has shown an interest in building an atomic bomb since the 1950s, its nuclear security concerns have been mollified by successive U.S. presidents through various agreements and a constant American troop presence on the Korean Peninsula.The arrangement now appears shaky. On Feb. 26, South Korea’s top diplomat, Cho Tae-yul, left open the possibility of developing weapons, publicly saying that nuclear armament was “not off the table.” It was the most significant shift in government sentiment since South Korea signed the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, the landmark international agreement signed by 191 countries that went into force in 1970 and prevents the spread of nuclear weapons and weapons technology.If South Korea sprints for the bomb, it could spur other signatories to follow suit. Japan and Taiwan, regularly facing military intimidation from China, may be forced to reconsider their options. In the Middle East, Iran is dangerously close to a full-blown bomb program, which could prompt Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Turkey and other nations to consider acquiring nuclear weapons. In short: more nukes, more problems for the United States and the wider world.American presidents had a challenging enough time avoiding nuclear conflict during the Cold War, when it primarily hinged on two nations — the United States and the Soviet Union — and on itchy trigger fingers constrained from releasing nuclear weapons pointed at each other. The idea of more nuclear countries and their regional baggage on the chessboard is frightening to fathom.To be clear, the president claims he has not parted ways with his predecessors in his views on nuclear proliferation. He has often talked about the scourge of nuclear weapons, and the day after Mr. Macron’s comments, Mr. Trump told reporters he was interested in pursuing disarmament agreements among world powers. “It would be great if everybody would get rid of their nuclear weapons,” he said. “It would be great if we could all denuclearize, because the power of nuclear weapons is crazy.”This is true, of course, but his policies are having the opposite effect. Thanks to Mr. Trump’s words and actions, the perceived value of acquiring nuclear weapons among allies appears to have quickly gone up, while the confidence in extended deterrence has gone down.If Mr. Trump truly believes nuclear weapons should go, he must act swiftly to cut short the proliferation debates taking place in foreign capitals and move to reassure allies that American extended deterrence policy is unshakable. If he is successful, he will save himself — and future presidents — the anguish of watching allies around the world amass new arsenals, only to hope later that the United States has some say in whether future wars may turn life-or-death for us all.W.J. Hennigan writes about national security issues for Opinion from Washington, D.C. He has reported from more than two dozen countries, covering war, the arms trade and the lives of U.S. service members.This Times Opinion series is funded through philanthropic support from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, Outrider Foundation and the Prospect Hill Foundation. Funders have no control over the selection or focus of articles or the editing process and do not review articles before publication. The Times retains full editorial control.The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected] the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp and Threads.

Keep Reading

Subscribe to Updates

Get the latest creative news from FooBar about art, design and business.

© 2025 Globe Timeline. All Rights Reserved.