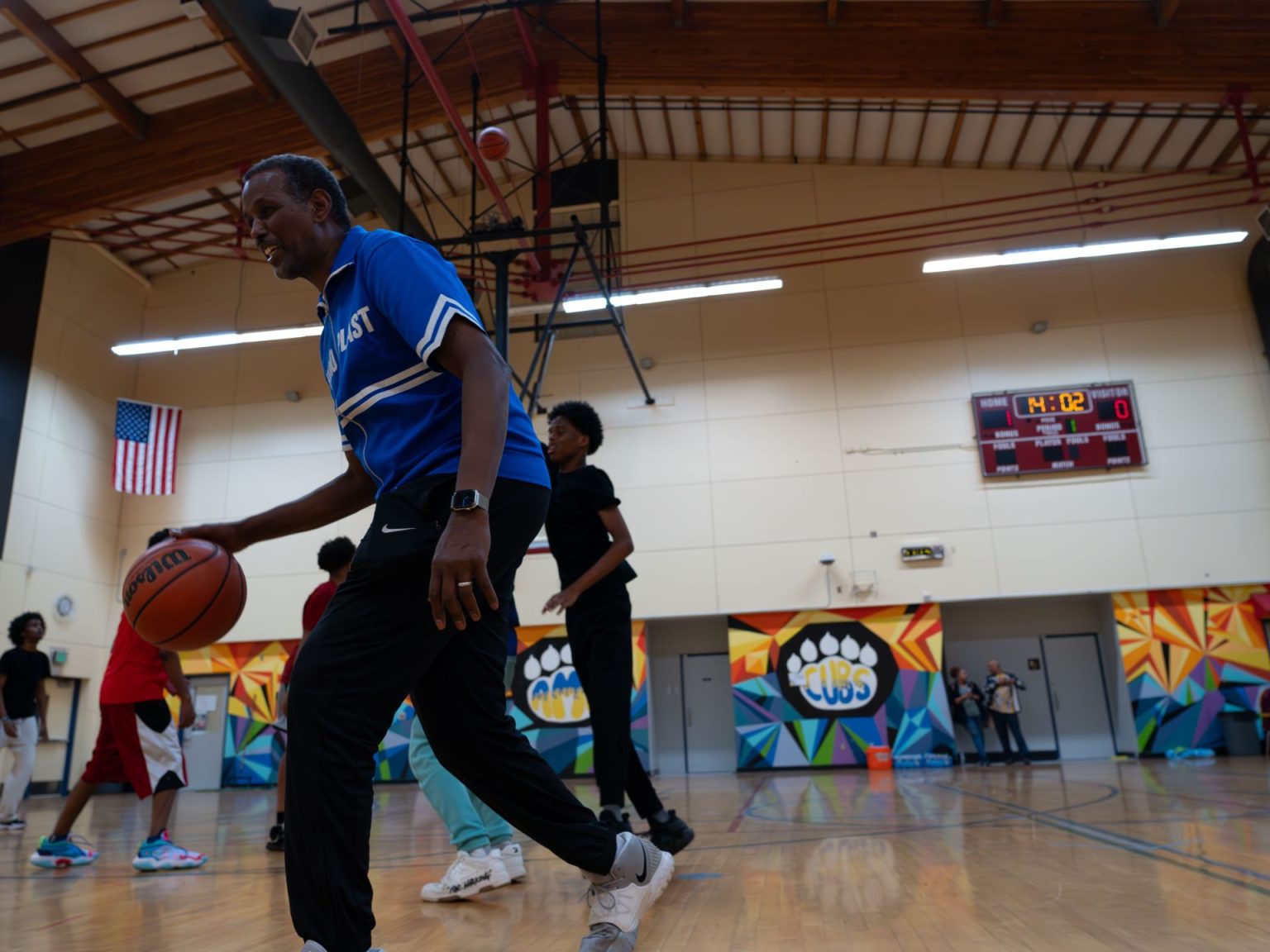

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs Ashland, Oregon – Inside the gymnasium at Ashland Middle School, basketballs are bouncing off the backboards and freshly waxed floors, footballs are being kicked between clumsily erected goalposts, and a group of girls is playing ping-pong in the corner.

But it is not a usual school day. Somali music blares from the sound system, and the crowd on the benches sings along. The gym’s double doors are propped open, letting in the morning sunshine and a steady stream of people with coffee cups in hand from the neighbouring hotel, where most of them have stayed the night.

Despite it being Memorial Day, this group of Somali athletes and their family members have gathered to commemorate their sacrifices. The blue and white of their national flag serves as a powerful backdrop for the long weekend, its five-point star a symbol of the unity the Somali people have fought so hard for.

Many of these people have not returned to their ancestral homes in decades.

Known for its scenic mountain ranges and Oregon Shakespeare Festival in Ashland, a small town with a vibrant art scene 26km (16 miles) north of the California border, there is this unlikely setting for one of the longest-running gatherings of the Somali diaspora in North America.

Since 2002, former players, coaches, and fans of the once-feted Somali national basketball team have met once a year in this small town for a weekend full of sports and storytelling.

When the Somali civil war and subsequent government collapse took place in 1991, these men and women went from being star players at the height of their careers to refugees in an instant.

Ali Mohamed, who has come to Ashland from his home in Atlanta, Georgia, says when he closes his eyes he can still see the crowds in the stadium and hear the thunder of their applause from his days on the Somali national team.

For him, basketball was a family legacy; his older brother had also played for the national team and earned the nickname “The Fox” because of his stealth and quickness on the court. Mohamed followed in his footsteps. “It was something that every kid dreamed of. It was an honour to represent the country, it was an opportunity that few people had.”

He remembers Somalia with the same nostalgia that colours his memories on the court. “Mogadishu was the jewel of Africa. It is still the most beautiful place I have ever been. It was a shame to see its destruction.”

Forced to start over in new countries, many of these players lost touch for years. But like the champion players they once were on the basketball court, they knew the game was not over until the buzzer rang.

Their greatest victory, they say, has been their ability to rebuild their lives from the ruins and displacement of the past. Once every year, they gather to celebrate what has endured – family and friendship, memories and dreams.

No wreckage, no rubble

The annual summer event in Ashland is hosted by Abdiaziz Guled, a goat herder-turned-all-star player who, as the tallest on the national team, played centre. His time on the team ended in 1987 after he was recruited to play for Southern Oregon University a few years before the war broke out in Somalia.

He now works as a youth advocate at Ashland Middle School, where he is affectionately known as “Bubba”.

Unlike the rest of his teammates, his memories of Somalia are unmarred by the tragedy of war. There is no wreckage, no rubble. He became a natural and much-needed focal point for those who endured it.

His warm welcome has transformed Ashland into a second home for all his guests. As one attendee says: “Abdi [Abdiaziz] has roots here. People know him and trust him. It’s like we’re coming to visit a long-lost family member. Here in Ashland, there are none of the stressors of a big city. No traffic or commotion.”

As word has spread, what began as an informal gathering of just a few friends has expanded to accommodate 75 to 100 people each year. The number of attendees fluctuates. In the 20 years since these players have gathered, elders have died and children have been born. No one knows who will show up each year or what new friends they will bring.

The weekend is jam-packed with activities – from hiking to swimming, tennis matches to basketball tournaments between young and old. Hours are spent sweating on the court or in the sun before a long evening full of “shaah iyo sheeko [tea and conversation]”.

Mohamed, a young man who has been visiting Ashland since he was 12, says: “When you’re younger, you’re just shooting baskets. As you get older, you realise what you’ve learned … the importance of brotherhood and the importance of your heritage.”

Hailing from places as widely spread as Atlanta and Washington DC, Seattle and Portland, Oakland and Ottawa, they gather each year in defiance of both distance and geography. The locus of their world may have once been basketball, but survival is also a triumph of its own.

Shiino Madoobe, who lives and works in Washington, DC, has been attending the gathering since 2010. He is one of several participants who consider Ashland a home away from home: “We are refugees. We cannot go home. We might not ever be able to. But we come to Ashland year after year. This is our time capsule.”

A time capsule serves two purposes, functioning as an archive of the past and a message to the future. Inside the Ashland Middle School gym, the past crashes headfirst into the present.

Transported to the past

At the start of the civil war, many of these athletes lost their livelihoods, their acclaim, and their country in one fell swoop. Safia Omer, who now lives in Oakland, where she is a mental health professional, and attends the gathering each year with her husband and two sons, was one such player. She was 16 and in her last year of high school when the war interrupted her athletic dreams and changed the course of her life. Here, in Ashland, she is still known by her girlhood nickname. “When I hear Safia Cadey, I am immediately transported to the basketball court, to my past,” she says.

It was the winter of 1991 when Omer’s team finished competing in the Zone 5 elimination matches of the All-Africa Games, being held in Ethiopia. They were meant to be away from home for only two weeks. They had each brought $200 of spending money with them on the trip.

It was December. “The tournament lasted for two weeks. At the end of the tournament, we spent a week sightseeing, just passing time until the political situation stabilised and it was safe to go home.” It never did; it never was.

The connecting flight that was meant to take them from Nairobi’s Jomo Kenyatta international airport to Mogadishu was delayed. “We waited and waited, but no plane came from Somalia. We waited for two days. It must have been 4 or 5 o’clock in the afternoon when a plane finally arrived.”

But when it did arrive from Somalia, only seven passengers disembarked with no baggage. They had fled the country in haste and were seeking asylum. The pilot told Omer and her teammates that if they didn’t want to be raped or killed they should not return to Somalia.

So, the group of 27 players, coaches and members of the team spent the next few days huddled around a radio that was their only connection to the outside world. They were not allowed to leave the airport or meet with the press.

It was from the airport that they heard that Bakaara, Mogadishu’s largest outdoor market, was burning. After years of political turmoil and failed rebellions, President Siad Barre’s government had fallen and the ensuing power vacuum would come to swallow everything in its path.

The airwaves delivered news of mass killings and destruction. “We slept in the airport for 10 days,” says Omer. “No one knew what to do with us.”

They used the airport toilets to shower and brush their teeth. Already, they were causing a stir. Members of the local Somali community brought them food each day and asked for their autographs.

United Nations officials eventually came to the airport to interview them and declare them refugees. They were moved to a military camp outside Nairobi that was guarded by Kenyan soldiers. They could not leave. Later they learned this was the political condition of refugees all over the world; regardless of circumstance, they were not seen by their reluctant hosts as victims but as potential security threats.

Their passports were returned to them upon their relocation, but they were now effectively useless as it was impossible to return to Somalia.

The group went from being star players whose faces decorated billboards and advertisements across Somalia to a stateless band of wanderers with nowhere to go.

A woman spectator calls out ‘Somalia ha noolaato!’ to the crowd, who repeat the phrase back to her: ‘Long live Somalia!’ [Salah Muhumed/Al Jazeera]

‘All we wanted was to make our people proud’

Omer completed her last year of high school in the refugee camp and was invited to play for the Kenyan national team, something she says now was strangely disorientating. Her final year of high school was spent moving back and forth between the pleasure and glory of a pristine basketball court and a crowded refugee camp.

By this time, the team had been moved to Thika Reception Centre 30 minutes outside Nairobi. It was a refugee camp which was initially established as a temporary holding camp for displaced people. Over the years, Thika has come under intense scrutiny for alleged human rights abuses.

Luckily, Omer’s sister was living in the United States and was eventually able to bring her to California where she helped her start her new life. She enrolled in school, learned English, and began playing basketball for UC Santa Cruz. The transition from representing a country to representing a college was not easy. It is an experience that she finds is best understood by those who lived through it with her: “It was the best and worst time of our lives.”

She looks around the gym. “The people I survived with in the refugee camp are the people I see here now.”

Teammates who once shared trophies, then tents, then arduous migration journeys that at times intersected and at times separated them, now gather to share memories. Their bond may have first been forged through the camaraderie of their shared sport, but it has been fortified by the horrors of war.

Omer’s former coach, Abukar Shiino, is also in attendance. He now lives in Edmonton, Alberta in Canada, and is the designated storyteller for the weekend’s festivities. Though he has traded in his playbook for a storybook, his role as orator is similar to the role he once filled as a coach.

In an oral culture like that of Somalia, stories are both currency and connective tissue. Each evening the group sits in a circle while Shiino dazzles the crowd with humorous stories that contain profound lessons.

He played for Somalia’s national basketball team from 1979 to 1989 while simultaneously coaching the women’s team. He recalls his years of representing his country with great fondness. “There are no words for it. It was always emotional to carry the name of the nation,” he says. “When we would win games, they would bring out the Somali flag and wave it over our heads. All we wanted was to make our people proud.”

‘Where is home?’

The notion of “home” is a recurring theme this weekend, eliciting both painful and poetic reflections. During a storytelling circle, one attendee asks the group: “Is my home Baidoa where I learned my mother tongue? Or is it Afgooye where my family lived on a dairy farm? Or is it Mogadishu where I learned to play basketball? Or is it Ottawa where I have now lived for even longer than I ever lived in Somalia?”

On the last night of the gathering, Guled wears his old team jersey. The team name and number on it have faded, but the jersey’s allure hasn’t. The children, many of whom have been attending this annual event since they were born, crowd around him. He takes it off and they take turns trying it on.

Many of the other players no longer have their jerseys having fled with only the essentials. But in Ashland, they’ve learned something that every good team figures out: together they are more than the sum of their parts. “We love each other not because of what we give to each other, but because of who we are to each other,” Madoobe says.

There may be no definitive answer to the question of where home truly is, but for this weekend at least, it is a small town on the west coast of the US, 9,000 miles from Mogadishu, where, after all these years, these former athletes still finish each other’s sentences, anticipate each other’s next move on the court, and pass the ball back and forth like the thread of a story.