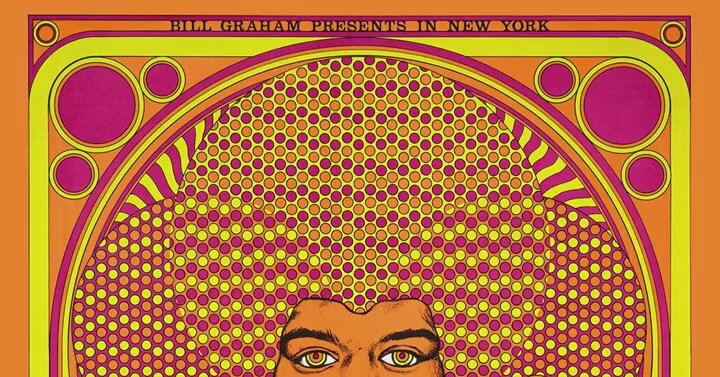

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs David Edward Byrd, who captured the swirl and energy of the 1960s and early ’70s by conjuring pinwheels of color with indelible posters for concerts by Jimi Hendrix, the Who and the Rolling Stones as well as for hit stage musicals like “Follies” and “Godspell,” died on Feb. 3 in Albuquerque. He was 83.His husband and only immediate survivor, Jolino Beserra, said the cause of death, in a hospital, was pneumonia brought on by lung damage from Covid.Mr. Byrd made his name, starting in 1968, with striking posters for the likes of Jefferson Airplane and Traffic at the Fillmore East, the Lower Manhattan Valhalla of rock operated by the powerhouse promoter Bill Graham.For a concert there that year by the Jimi Hendrix Experience, Mr. Byrd rendered the guitar wizard’s hair in a field of circles, which blended with the explosive hairstyles of his bandmates, Noel Redding and Mitch Mitchell.Mr. Byrd also put his visual stamp on the Who’s landmark rock opera, “Tommy,” producing posters for it when it was performed at the Fillmore East in October 1969 and again, triumphantly, at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York a few months later. In 1973, he shared a Grammy Award for his illustration work on the London Philharmonic Orchestra’s rendition of “Tommy.”For his poster for the Rolling Stones’ 1969 U.S. tour, which culminated in the violence-marred Altamont festival in Northern California, Mr. Byrd paid no mind to the band’s increasingly sinister image. Instead, he opted for an illustration of an elegant female nude twirling billowing fabric, drawing for inspiration on the late-19th-century motion photographs by Eadweard Muybridge.Mr. Byrd’s theater work included a surreal poster for “Follies,” the bittersweet 1971 Broadway evocation of the Ziegfeld Follies era with music and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim. The design featured the cracked face of a somber-looking woman wearing a star-studded headdress that spelled out the show’s title.The poster was enough of a hit that the producer Edgar Lansbury called Mr. Byrd in for a meeting at his office near the Winter Garden theater, where “Follies” was playing, and asked him to design one for the Off Broadway production that same year of “Godspell,” the flower-power retelling of the Gospel of St. Matthew.In his 2023 book, “Poster Child: The Psychedelic Art & Technicolor Life of David Edward Byrd,” written with Robert von Goeben, Mr. Byrd recalled Mr. Lansbury telling him to peer out the window at his “Follies” image.“I want that poster,” he said, “and I want it to be Jesus.”Mr. Byrd missed out on a brush with history when his original poster for the Woodstock Music and Art Fair in 1969, featuring a neoclassical image of a nude woman with an urn, was replaced for various logistical reasons by Arnold Skolnick’s — the now famous image of a white bird perched on a guitar neck. Mr. Byrd took it in stride.“I didn’t think of it as any kind of ‘branding’ for the event,” he said of his poster. “I thought of it as a souvenir of the event.”Mr. Byrd was impressed by — and to a degree, aligned with — the work of the so-called Big Five psychedelic poster artists of San Francisco: Alton Kelley, Rick Griffin, Victor Moscoso, Stanley Mouse and Wes Wilson, who were known for using kaleidoscopic patterns, explosions of color and fonts that seemed to bend and ooze like Salvador Dalí clocks.But, based 3,000 miles from the Haight-Ashbury scene, Mr. Byrd was also influenced by Broadway and advertising, employing standard typefaces and drawing on the Art Nouveau movement of 1890s Europe. His work is “kind of like Art Nouveau on acid,” said Thomas La Padula, an adjunct professor of illustration at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, where Mr. Byrd taught in the 1970s.Throughout, however, Mr. Byrd could enjoy the unfettered freedom afforded by the music world in those days. “With rock, there was no basic subject matter,” he wrote in “Poster Child.” “It was just whatever you wanted to do that was eye-catching.”David Edward Byrd was born on April 4, 1941, in Cleveland, Tenn., the only child of Willis Byrd, a traveling salesman, and Veda (Mount) Byrd, a part-time model. His parents divorced when he was young, and he spent most of his youth in Miami Beach with his mother and his wealthy stepfather, Al Miller, an executive with the Howard Johnson’s restaurant chain.After receiving a bachelor’s degree in fine art and a master’s in stone lithography from Andy Warhol’s alma mater, the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh (now Carnegie Mellon University), he settled in an upstate New York commune, where he was painting in the vein of Francis Bacon, the Irish-born artist and master of the macabre, when college friends, including Joshua White, who designed the dazzling light shows for the Fillmore East, hooked him up with Mr. Graham.Fillmore East closed in 1971, but that did not mark the end of Mr. Byrd’s work in music. For a Grateful Dead concert at the Nassau Coliseum on Long Island in 1973, he came up with an impish illustration of two clean-cut 1950s teenagers boogieing under the self-consciously corny tagline “A Swell Dance Concert.”Mr. Byrd also produced a retro-inflected album cover for Lou Reed’s 1974 album, “Sally Can’t Dance,” as well as posters for the band Kiss. He made a foray into Hollywood with his poster for the 1975 film adaptation of “The Day of the Locust,” Nathanael West’s dystopian Hollywood novel.Mr. Byrd moved to Los Angeles in 1981 and worked there as the art director for Van Halen’s “Fair Warning” tour. Later that decade, he spent four years as the art director for the national gay news publication The Advocate, and in the 1990s he worked as an illustrator for Warner Bros. on its consumer merchandise.He and Mr. Beserra, a mosaic artist, moved to Albuquerque last year.Mr. Byrd often said that he found the making of art more fulfilling than the end result. “The final art product is merely the doo-doo, the refuse, the detritus of the creative experience,” he said in his book. “The golden moments in my life have always been the personal, magical world of the ‘Aha!’ moment.”

Subscribe to Updates

Get the latest creative news from FooBar about art, design and business.

© 2026 Globe Timeline. All Rights Reserved.