A new study led by researchers from the University of British Columbia (UBC) and Simon Fraser University (SFU) in collaboration with the Medical Research Council (MRC) Unit The Gambia has found a genetic signature in newborns that can predict neonatal sepsis before symptoms even appear. Neonatal sepsis is a severe infection that affects around 1.3 million babies globally each year, with higher rates in lower- and middle-income countries (LMICs). The study, funded by the National Institutes of Health and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, aims to help healthcare workers diagnose infants earlier to prevent the lifelong effects of sepsis.

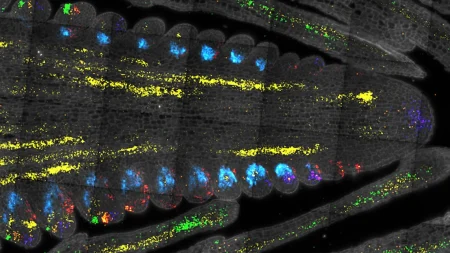

Diagnosing neonatal sepsis is challenging as the symptoms can mimic other illnesses, and traditional tests can take days, are not always accurate, and are usually only available in hospitals. Early diagnosis is crucial as delayed treatment with antibiotics can have severe consequences. The researchers used machine learning to analyze genetic markers in newborns to predict sepsis. They identified four genes that, when combined in a “signature”, accurately predicted sepsis in newborns with a success rate of ninety percent. This groundbreaking research provides an opportunity to treat infants promptly and prevent long-term health issues.

Neonatal sepsis causes an estimated 200,000 deaths worldwide annually, with the highest rates in LMICs. In Canada, the risk is lower, but premature babies are at a higher risk. Dr. Bob Hancock, a professor at UBC, emphasizes the importance of early diagnosis in saving lives, especially in vulnerable individuals. The researchers conducted a study in The Gambia, where blood samples were taken from 720 infants at birth, and identified 15 cases of early-onset sepsis. This research provides a unique opportunity to predict sepsis before symptoms appear, unlike previous studies that focused on markers present in sick infants.

Dr. Amy Lee, an assistant professor at SFU, highlights the significance of these findings in predicting neonatal sepsis. By analyzing gene expression at birth, the researchers were able to develop a predictive signature that could revolutionize the diagnosis of sepsis in newborns. Dr. Beate Kampmann, who led the clinical component of the study at the MRC Unit in The Gambia, emphasizes the importance of early recognition of sepsis for infant survival. The researchers envision incorporating this signature into portable, point-of-care devices that can be used anywhere with a power source, enabling quick and accurate diagnosis by non-experts.

The next steps for the research involve conducting a large prospective study to validate the predictive signature in different populations and develop point-of-care tools for approval by government bodies. Dr. Hancock suggests that existing point-of-care devices used for testing gene expression in diseases like COVID-19 and influenza could be adapted to recognize the sepsis signature, making it accessible and affordable for healthcare providers worldwide. The potential impact of this research on infant health, particularly in LMICs where sepsis rates are higher, is significant and could save many lives by enabling early detection and treatment of neonatal sepsis.