Researchers from the University of Florence, Harvard University, and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology used ancient DNA to challenge long-held interpretations of the people of Pompeii. The genetic data revealed unexpected variations in gender and kinship, revising the story as written since 1748. The DNA evidence also highlighted the cosmopolitan nature of the Roman Empire, showing that Pompeians were mainly descended from immigrants from the eastern Mediterranean.

In 79 AD, Mount Vesuvius experienced a significant eruption, burying the Roman city of Pompeii and its inhabitants under a thick layer of small stones and ash known as lapilli. Many residents perished as their homes collapsed due to the weight of the lapilli. The survivors eventually succumbed to the dangerous pyroclastic flows, which instantly enveloped their bodies in a solid layer of ash, preserving their features. Since the 1800s, plaster casts had been made from the voids left by these bodies after their decay.

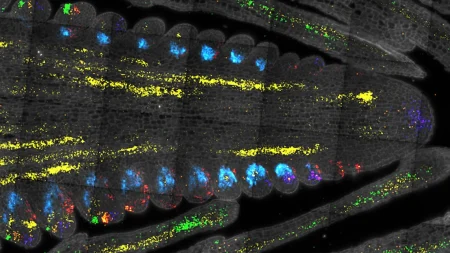

The research team extracted DNA from the skeletal remains embedded in 14 of the 86 famous casts undergoing restoration. This allowed them to establish genetic relationships, determine sex, and trace ancestry accurately. The findings contradicted previous assumptions based solely on physical appearance and cast positioning. The genetic analysis challenged enduring notions linking jewellery with femininity and physical proximity with familial relationships, adding a layer of complexity to kinship narratives.

The genetic data revealed surprising information about the victims of Pompeii, challenging traditional interpretations. For instance, an adult wearing a golden bracelet and holding a child, traditionally thought to be a mother and child, were found to be an unrelated adult male and child. Similarly, a pair of individuals believed to be sisters or mother and daughter included at least one genetic male, questioning gender and familial assumptions. The ancestry of the Pompeians was also diverse, with most descending from recent immigrants from the eastern Mediterranean.

The study showcased the importance of integrating genetic data with archaeological and historical information to avoid misinterpretations based on modern assumptions. It highlighted the cosmopolitan nature of Pompeii’s population, reflecting broader patterns of mobility and cultural exchange in the Roman Empire. The use of genetic data and other bioarchaeological methods provides a better understanding of the lives and habits of the Vesuvius eruption victims. The Pompeii Park has been including ancient DNA analysis in its study protocols for both human and animal victims, contributing to a more comprehensive interpretation of archaeological findings.

The Pompeii Park conducts various research projects, including isotopic analysis, diagnostics, geology, volcanology, and reverse engineering, through its laboratory. These efforts contribute to advancing archaeology and research, making Pompeii a hub for the development of new methods and resources. The integration of different scientific elements marks a true change in perspective, with the site playing a central role in advancing archaeology and research. The study emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration in shedding new light on ancient societies and historical events.