A federal judge in Los Angeles on Friday questioned the Biden administration’s stance on whether it bears responsibility for housing and feeding migrant children waiting in makeshift camps along the U.S.-Mexico border. The Border Patrol does not dispute the poor conditions at these camps, where migrants wait for agents to arrest and process them. The issue at hand is whether these migrants are in legal custody, which would trigger certain protections for children, including a 72-hour limit on detention and emergency medical services. The judge questioned whether the migrants were free to leave the camps, prompting a discussion on legal custody definitions.

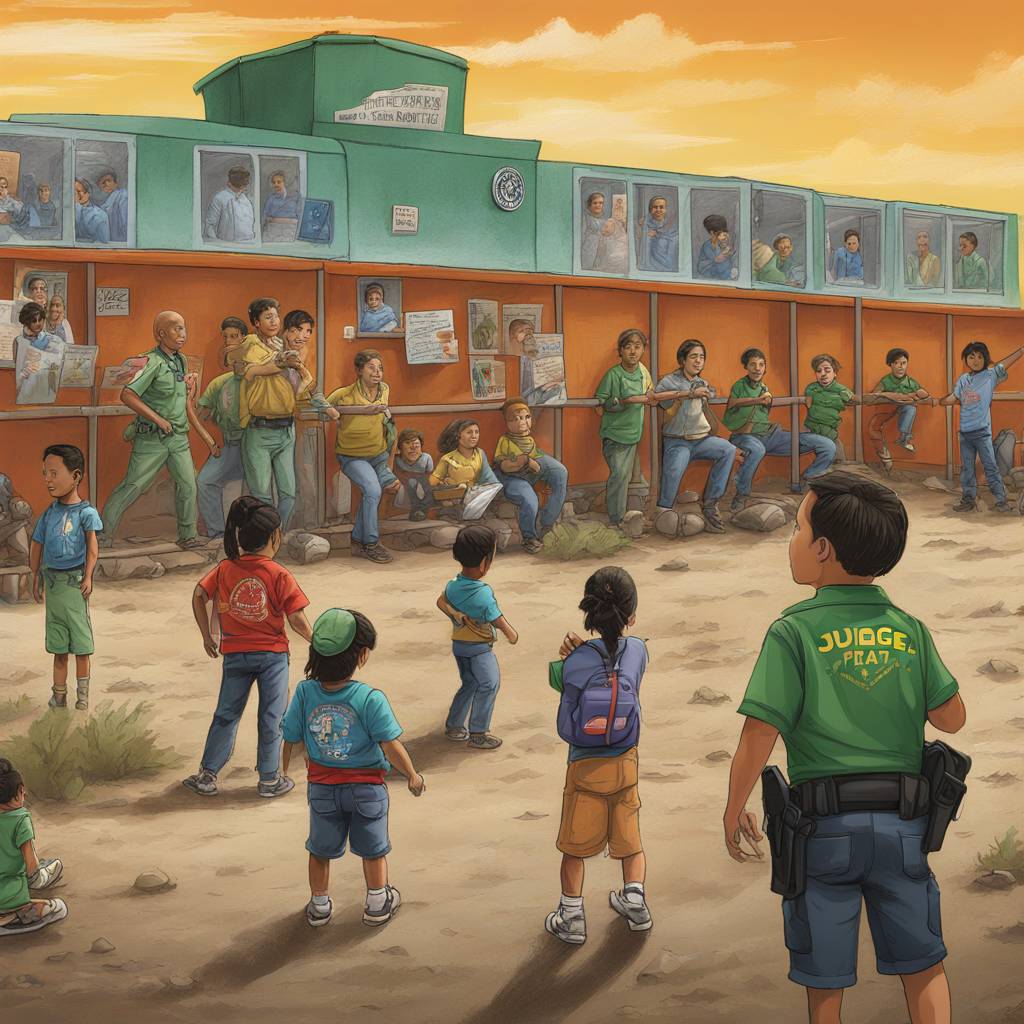

The migrants in these camps are primarily families and children who have crossed the border illegally and are waiting to be processed by Border Patrol agents. Advocates argue that the migrants are effectively in custody and deserve certain protections under a court-supervised settlement on custody conditions for migrant children. This includes access to basic necessities like toilets, sinks, and temperature controls within the camps. The judge did not issue a ruling after the hearing, as the situation is complex given that some children arrive at the camps on their own and are not sent there by Border Patrol agents.

Children traveling alone are supposed to be transferred within 72 hours to the U.S. Health and Human Services Department, which then releases them to family in the United States while their asylum cases are being considered. Families are usually released in the U.S. as well, as they await their court hearings on asylum claims. The legal challenge is focused on two specific areas in California, where migrants were waiting for days to be processed by overwhelmed Border Patrol agents last year. Advocates argue that agents often direct migrants to the camps, and the Justice Department disputes the characterization of these sites as “open-air detention sites.”

The Border Patrol notes that the agency has been working to speed up the processing of migrants at these camps, with agents generally arresting them within 12 hours of encountering them. The number of buses in the San Diego area has also been doubled to facilitate quicker processing. On the ground, volunteers like Pedro Rios provide food and medical aid to the migrants waiting in between the border walls. Migrants come from various countries, including China, India, Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, and primarily communicate with agents in English. The conditions at the camps, coupled with the challenges of navigating the asylum process, highlight the difficult choices and experiences faced by migrants seeking refuge in the United States.

One migrant, Kedian William from Jamaica, shared her story of leaving her daughter behind due to financial constraints and health issues. She hoped to apply for asylum and reunite with family in New York after fleeing violence in her home country. With the help of volunteers like Rios, she and other migrants at the camps receive basic necessities and support as they navigate the uncertain and often harsh realities of the immigration system. As the legal battle over the responsibility for housing and feeding migrant children continues, the fate of these vulnerable populations along the U.S.-Mexico border hangs in the balance.