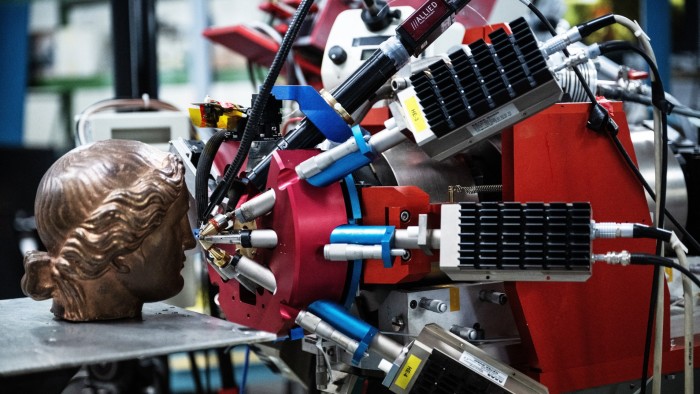

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic Unlock the Editor’s Digest for freeRoula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.When I worked at Christie’s as a student intern one summer, the library of the book collector William Foyle came up for sale. There were around a thousand lots sold over three days. Only one book was withheld, never put up for sale. It had a Nazi stamp inside it.The rise of provenance research — the documented history of an object — is directly connected to the forced sales, appropriations and thefts during the second world war. So much cultural heritage changed hands illegally that there is significant danger that a past owner will intervene with a sale. It can get messy, both morally and legally.Art is authenticated in three main ways. The oldest is connoisseurship: experts (often self-proclaimed as such) provide their opinion as to who created an artwork. Provenance research is the second, which means gathering documents and historical references to the object in question, which attest to generations of experts agreeing on its authenticity and a paper trail affirming its legal ownership. The third is forensic testing. The art trade has always used forensic testing as a last resort, a tiebreaker when experts disagree or the provenance raises a red flag. There is no good reason for this. Forensic testing need not be expensive or invasive — it often just involves looking at an object with different light spectra (X-rays, infrared, ultraviolet). But the art trade has always functioned on gentleman’s agreements and the opinion of connoisseurs. A forensic test would either confirm what the expert already said (thereby not necessarily adding value from a business perspective) or contradict the expert (in which case the expert loses face and the art trade loses out on a potential sale). None of the forgeries I’ve studied would stand up to basic forensic tests — a good-looking provenance made an object appear good enough to sellIn the history of forgery, tricksters have often created “provenance traps” to take advantage of the trade’s over-reliance on provenance. The basic premise is that the forger passes off their forgery as a lost work by a renowned artist, and a breadcrumb trail of provenance (original or forged documents) is followed by the enthusiastic expert, who feels they are on a real-life treasure hunt. Almost none of the forgeries I’ve studied would stand up to basic forensic tests. They didn’t have to, because a good-looking provenance made an object appear good enough to sell. But we’ve entered a new age of mistrust. Populism mistrusts experts. Experts mistrust data because, in the age of AI, photographs and texts and even videos can be forged so seamlessly that it can be well nigh impossible to distinguish fact from fiction. Provenance, which deals primarily with musty archival documents, feels more tangible than opinion and less liable to be manipulated than scientific tests that most people don’t understand. So, where to go from here?Technology can manipulate and mislead, but it can also be harnessed for good. Consider outfits like the Paris-based C2RMF which uses the latest forensic tools to examine pigments and analyse works with varied light spectra. Researchers at the British Museum are currently using advanced techniques such as CT scanning, molecular and isotopic analysis, and radiocarbon dating in a study of Egyptian animal mummies, revealing the methods used by ancient embalmers. There are new initiatives, too, such as the Zurich-based Art Recognition (which I have joined as an advisor), which uses AI models to authenticate artworks, as well as assessing where several artists may have been involved (for instance, through heavy-handed restorations that can muddy the waters of connoisseurship).At this year’s Art Business Conference at Tefaf in Maastricht, Art Recognition founder Carina Popovici will give a talk about a recent case. They tested a “Bath of Diana” painting from a private collection, via a curated data set that included 329 images of confirmed Rubens works, as well as 316 images of non-authentic works used to teach the AI what not to be tricked by. The result confirmed that the painting is partially by Rubens (and it specified which parts).While chemical analysis and light spectra imaging are good at spotting anachronisms (a pigment that post-dates the supposed creation of a painting, or a lack of underdrawings on a canvas that should have them), these tools aren’t as good at identifying authorship. AI art analysis is, provided you have a closed, well-curated data set stocked with images by the presumed artist. Forgers have always understood that they don’t have to make such brilliant forgeries, provided their provenance trail is sufficiently compelling. If all artworks up for sale were expected to have forensic results accompanying them, along with expert opinion and provenance documentation, then we’d see far fewer attempts. It has never been so easy to analyse art scientifically. Such mandatory forensics testing would bring some much-needed peace of mind to the market.Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning

رائح الآن

rewrite this title in Arabic Why the art trade should learn to love forensics

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2026 جلوب تايم لاين. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.