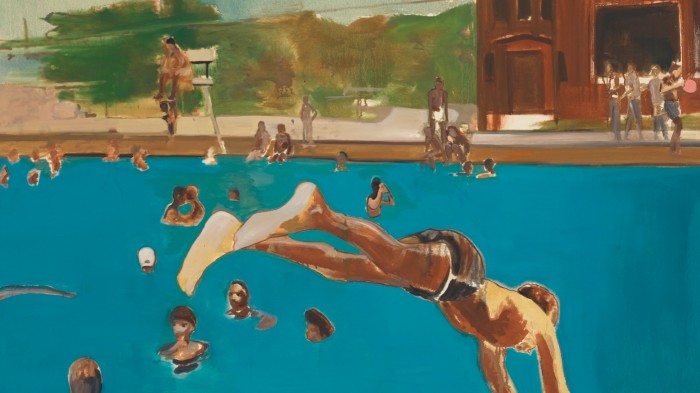

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic At the centre of the Barbican’s mesmerising, heartbreaking retrospective of African-American painter Noah Davis, an angel is about to take flight. Raising her arms, a young Black woman in a gold sequinned leotard unfurls two big fans as wings, smeared with yellow house paint, and poses in the yard of a white wooden Los Angeles home. “Stand there! You are Isis!” Davis exclaimed to his wife Karon. “He snapped the pic and quickly retreated to paint it,” she recalled.“Isis” (2009), a characteristically moody, slightly blurry composition in restrained hues and loose strokes of thin dilute paint, but full of feeling, also contains Davis’s self-portrait: a smudgy reflection in the window as he takes the photograph on which the painting is based. He is Osiris, Egyptian god of the dead; Karon is Isis, the healing goddess who cast the spell to make the dead Osiris whole again and immortal. It is a beautiful, prophetic painting. In 2013 Davis was diagnosed with terminal cancer and in 2015 he died, aged 32. “My assignment is gathering these parts of my love and protecting them,” Karon Davis says of the works here.A decade later, it is clear that no American figurative painter of his generation matches Davis’s virtuosity, humanity, individual vision, authoritative engagement with art history and sheer haunting loveliness.Transforming photographic sources into a bewitched realism, one moment he makes a trio of Black youths standing in the grisaille of an LA doorway, lost in thought, in “Congo #7” (2014), as mysterious and nostalgic as Eugène Atget — his 1920s series “La Villette Rue Asselin” is one reference. The next, a flurry of dynamic figures diving and bobbing in a public swimming pool in “1975 (3)” and “1975 (8)” (both 2013), based on Davis’s mother’s snapshots of her childhood, become joyous depictions of Black people at leisure, surreally enhanced.Concerned with community and the liminal, motion and transition, and through it all paint’s transporting power to reverie, Davis set out to “take these anonymous moments and make them permanent. I wanted Black people to be normal.” Born in Seattle, he was an urban painter to the core, and especially memorialised his adopted home of LA, at large scale — as in the nocturne light-scape “LA Nights” (2008) — and building by building, person by person. In “The Architect” (2009), a suited Black man looks down at a model converging a pyramid — continuing the Egyptian allusions of “Isis” — with a modernist building’s crisp, clean planes. Flamboyant white splashes veil the figure, based on Paul Revere Williams, a rare prominent Black architect of major LA buildings, notably The Beverly Hills Hotel. Williams learnt to draw upside down because he intuited that his white clients were uncomfortable sitting next to him. Here the viewer is on the other side of the architect’s table.Davis hero-worshipped Williams. “It seems like you start off as a painter, and then you kinda see your place in society as kind of like this urban development,” he said. The Barbican’s well-chosen retrospective — organised with Das Minsk, Potsdam, and Los Angeles Hammer Museum — unfolds exactly this bold, sadly brief trajectory.To begin, the gossamer fantasy “40 Acres and a Unicorn” (2007): the mythical animal and child rider trot at us out of velvety darkness, carrying stories of disillusion — the broken promise to former enslaved people of “40 acres and a mule” — yet capacity to hope and dream. Similarly fabular and melancholic, a portrait of imminent grief, is the man standing on the brink of a starry abyss, holding a lamp: “Painting for My Dad”, completed in 2011 as Davis’s father Keven — a high-profile lawyer whose clients included Venus and Serena Williams and Wynton Marsalis — was dying.Davis Sr bequeathed his son funds for a community art centre, and in 2012 Noah and Karon founded the Underground Museum in Arlington Heights. The aim was to bring “world-class art” to a deprived neighbourhood, but no lenders were forthcoming. So Davis did two things.First, he repurposed the buildings’ LED strip lights as imitation Dan Flavins, and put a $70 vacuum cleaner in a display case as a knock-off Jeff Koons — a painter’s jest against expensive conceptualism. Second, he painted the missing world-class art himself, with the accent on architecture.The series The Missing Link (2013) and Pueblo del Rio (2014) are his masterpieces: deeply considered portrayals of the unspectacular everyday as iconic yet suggestive of other, better possibilities.The setting for “The Missing Link 4” is Mies van der Rohe’s modernist development Lafayette Park in Detroit: a housing block’s steel and glass facade, a chequered grid in blue, brown and black, glimmers above a pool with Black figures swimming and playing, rendered in lush expressive sweeps and drips. In “The Missing Link 3”, a smart Black man with a briefcase is the sole figure in a monumental pattern of squares and cubes; a hazy purple rectangle — inspired by over-painted graffiti that Davis had photographed locally — is a cross between an actual wall, a painted wall and an imitation of a Rothko abstraction. Throughout the series, the tension is between painting’s discipline and drive to form an image, and spontaneous, free mark-making.Pueblo del Rio features an LA housing project designed by Williams, reimagined by Davis as an enchanted arena for art and music in an inner city neighbourhood — the actual Underground Museum in idealised form. A lone young Black piper, recalling Manet’s “Fifer”, is silhouetted at dusk against modernist white slabs and the shadows of trees in “Prelude”. In “Arabesque”, the spotlit buildings are the stage for rhythmic Black dancers in white tutus — Degas transmuted to LA. Girls in hoodies stare at a hoodie-shaped object in “Public Art Sculpture”; a burst of colour comes in the patchwork trousers of a woman crossing the road in “Stain Glass Pants”.The uncanny “The Conductor” (2014), on a wall by itself, the show’s greatest work, is perhaps a wistful self-portrait; framed by a bluish-grey monument dissolving in liquid washes and shadows, translucent, ineffable, a lone Black figure stands on a chair waving a baton, as if in an improvised final performance. Had we but world enough, and time . . . At the door to Davis’s Underground Museum a banner read “this is a Black space but all are welcome.” So too with his work, political in a broad sense, yet extremely open. For if he mines older contemporaries — Peter Doig’s hallucinatory settings, Luc Tuymans’ bleached out surfaces, Kerry James Marshall’s insertion of the non-traumatic Black figure in the modern canon — he also creates his own world, unbound by time. Painting, Davis said, “has a history so vast and forgotten that it can only exist in the land of the spirits”. How brilliantly he conjures them from the past into an eternal present.February 6-May 11, barbican.org.uk, then Hammer Museum Los Angeles June 8-August 31, hammer.ucla.eduFind out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning

rewrite this title in Arabic Why Noah Davis is the greatest American figurative painter of his generation

مقالات ذات صلة

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2025 جلوب تايم لاين. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.