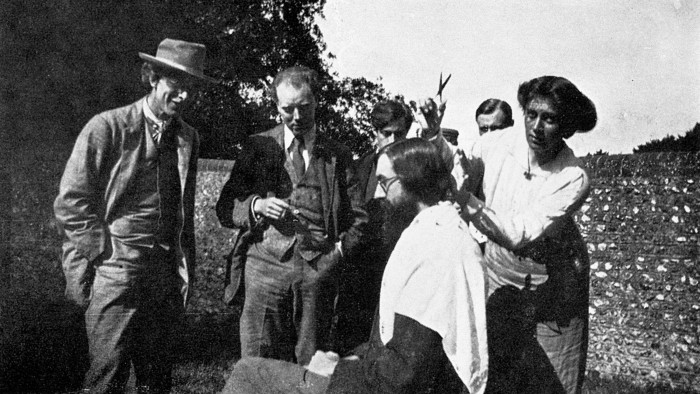

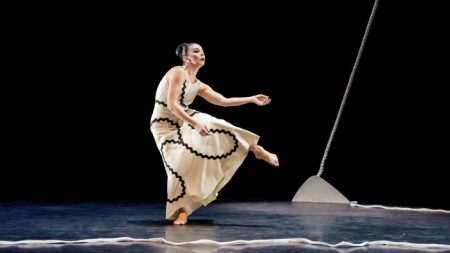

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic Unlock the Editor’s Digest for freeRoula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.The Bloomsbury Group is the subject of a shelf-bowing number of books and still holds a particular fascination. In their permissive attitude towards sex, their rejection of social convention and reverence for individual freedom, we rightly discern in this circle of artists and writers a nascent version of 21st-century attitudes. Wendy Hitchmough’s Vanessa Bell: The Life & Art of a Bloomsbury Radical, is likely, then, to find a receptive audience.But any book seeking a place on that crowded shelf must justify its inclusion. In the case of Bell, who is already the subject of an excellent biography by Frances Spalding, this is particularly true. Hitchmough — who was curator at the Bloomsbury artist’s Sussex home, Charleston, for 12 years — pitches her book as a corrective. She argues that Bell was hampered by prejudice in a male-dominated field, and that her importance as a female artist “in the vanguard of modernism” has been undervalued. We are to come away from her book with a new understanding of Bell as the radical “matriarch” of the post-Impressionist scene.Drawing on Bell’s previously unpublished letters, Hitchmough uncovers a litany of instances when the men in the Bloomsbury Group either took credit for or obscured her work. Much of Bell’s labour, she writes, was “invisible”. While Bell was clearly the co-host (alongside her sister Virginia Woolf) of the first Bloomsbury meetings — during which the whole edifice of stuffy Victorian culture was dismantled — it is her brother Thoby Stephen who is credited. And though her husband Clive Bell became an important art critic, her role in supplying him with opinions and introducing him to the work of artists like Cézanne, Matisse and Picasso goes unacknowledged.Hitchmough uncovers a litany of instances when the men in the Bloomsbury Group either took credit for or obscured her workRoger Fry, her Omega workshop partner and lover, is credited by reviewers for their success at the 1913 Ideal Home Exhibition, despite most of the work being Bell’s. When we think of Charleston, even, we imagine an idyllic scene but fail to see Bell cleaning, mothering, stretching canvases — furiously pedalling below the surface.Hitchmough finds Bell’s lover, the painter Duncan Grant, to have caused the most damage. Because their work is so similar in style and often unsigned, art historians have frequently misattributed her work to him. While it was Bell who first “singled him out as a rising talent” at the Friday Club (a salon also organised by her) and continued to promote his work over her own, “it was Duncan who was heralded as ‘the best English painter alive’” by her own husband. In her relationship with Grant, her tendency to self-sacrifice — behaviour that she learnt at the hands of her oppressive father, who “conditioned [her] acceptance of selfish, unregulated behaviour” — was at its most extreme.This is all no doubt true, and entirely convincing as an argument (although it cannot be considered new). But does it make for a good book? The generously printed colour images of Bell’s paintings alongside Hitchmough’s attentive analysis bring her work to life, but Bell herself is barely resurrected. Hitchmough’s insistent argument gets in the way. If it weren’t for the letters, which give us brief flashes of a woman who was clearly as “singularly alive” as the portraits she painted — full of caustic wit and radical daring — this book would read more like a curator’s catalogue.We can all stomach a little polemic, and even a sizeable portion of undiluted facts, as long as they come with a side of scene-setting and characterisation. In fact, we are far more easily convinced of an argument if it has been brought to life. But without those necessary literary elements, it all starts to become a bit static. Hitchmough makes no attempt to show Vanessa holding court at the Friday Club or painting on Studland beach. She writes that Grant and Duncan “shared a visual vocabulary” but we are never invited to eavesdrop on their conversations. For a book that promises to give us something of the life of Bell, there is very little in it that moves.During her BBC Reith lectures, the late Hilary Mantel explained that the historical novelist aspires to make “these bones live”. It is an ambition shared by the greatest biographers. From the “dead fact”, as Richard Holmes writes, “somehow you have to produce the living effect”. The task is to find the balance between fact and art, between information and invention; to, in the words of Virginia Woolf, “produce something of the intensity of poetry, something of the excitement of drama”. Collecting information and shepherding it around an argument is not enough. A writer’s job is to galvanise the dead fact into life.Vanessa Bell: The Life & Art of a Bloomsbury Radical by Wendy Hitchmough, Yale £30, 352 pagesJoin our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café and follow FT Weekend on Instagram and X

رائح الآن

rewrite this title in Arabic Vanessa Bell: The Life & Art of a Bloomsbury Radical — portrait of a modernist artist

مقالات ذات صلة

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2025 جلوب تايم لاين. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.