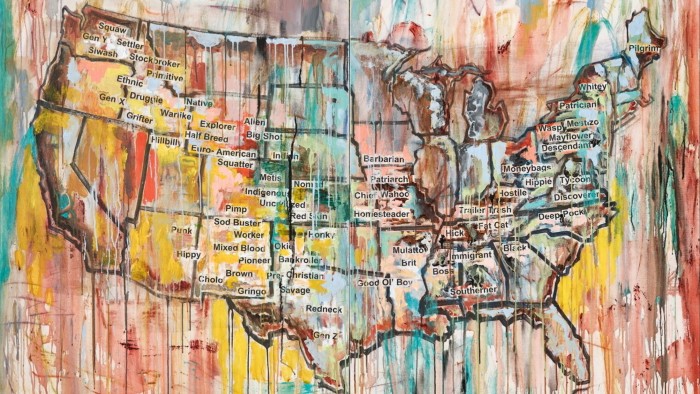

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic Art’s status as an asset remains up for debate, but as its proponents grow more sophisticated, there are signs that this fragile field could reap rewards for some.Wealth managers have certainly had their heads turned — in 2023, 90 per cent of 435 art and finance stakeholders surveyed by Deloitte and ArtTactic believed that art and collectibles should be part of an investment portfolio, up from 53 per cent in 2014. “The conversation has shifted from whether art should be part of a wealth management offering to how it can be implemented effectively,” finds its latest report.One company thinks it has hit the jackpot: a Sweden-based art fund called Arte Collectum, which raised €20mn of outside investment in 2022, all now spent, and has started its second fund. Its strategy is to buy overlooked but market approved artists, often women and people of colour. “Female artists and artists outside the western canon have historically been valued about 20 times lower [than their male, western counterparts]. Now perhaps it is five times, but the gap still exists,” says Lars Nittve, a museum veteran who is now chair of Arte Collectum’s investment committee and a partner in the business. Its first fund owns 45 works, including by the Colombian textile artist Olga de Amaral, Senegal-born mixed media painter Omar Ba and Native American artist Jaune Quick-to-See Smith.Funds such as these aim to widen access to the art market by pooling outside investment to buy works. They generally mix financial and art experience among their management: Arte Collectum’s co-founder and chief executive is Jonas Höglund, a finance professional, while its investment committee also includes Deborah Gunn, who previously managed the art collection of Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen. Its funds are registered with Euroclear and publicly traded, while approved distributors include Nordea and SEB banks. Nittve says he was partly attracted to the role “because they have a proper [regulatory] structure, they are not a cowboy effort” — an indication of art funds’ relatively patchy history.The most recent crop, including Arte Collectum, model themselves on a traditional private equity business, with a five- to 10-year investment term and a “two and 20” compensation structure — that is, taking two per cent of the value of their assets as an annual fee from investors and then 20 per cent of any profits when these are sold on. They target returns, net of fees, that average between 10 and 20 per cent per year — Arte Collectum aims for 12 per cent.Come the early 2000s, when the art market seemed to be on a permanently upward trajectory, such investment vehicles appeared in many corners of the world, then disappeared soon after the wider art market crash of 2008-09. The Fine Art Fund, founded in 2004, proved more resilient and raised five such funds that, combined, generated a 15 per cent gross compound return by the time they all closed in 2021, says founder Philip Hoffman. He adds that this percentage was “before management and regulatory fees,” which, he concedes, amounted to “quite a chunk” — pointing to one of the problems inherent in these investment vehicles.More broadly, Hoffman says, “psychologically, nobody wants to buy from an art fund. If you’re selling, they think it must be at the top of the market.” For this reason, he says, regulated funds are arguably hampered by the accompanying need for transparency as everyone knows what they own. His business has since widened to offer art investment advice as well as art lending, and is now called The Fine Art Group. Hoffman doesn’t rule out starting another art fund this year but “it would be done privately and discreetly,” he says.Nittve believes that his previous museum directorships — including at Hong Kong’s M+, Stockholm’s Moderna Museet and London’s Tate Modern — help Arte Collectum have an edge in an insider’s field. “The key is that we can get access to really good works on the primary market,” he says. Lending to museum shows, which ups art’s cultural and financial value, is also core to Arte Collectum’s strategy and something that Nittve sees as win-win for the art ecosystem. “It adds to the artist’s CV and museums feel they have a duty to recalibrate what they are showing,” he says. Other loans include de Amaral’s glittering gold leaf wall-hanging “Strata XV” (2009), in the artist’s ongoing solo show at the Fondation Cartier in Paris.Nittve’s recent highlight, he says, was when the fund loaned a vividly-coloured, untitled 1960s painting by the Korean artist Wook-kyung Choi to the Whitechapel Gallery’s 2023 touring Action, Gesture, Paint: Women Artists and Global Abstraction, 1940-1970. The work became the poster image for the show, helping “to bring out an artist that no one in the west had really heard of,” Nittve says. While he is keeping his cards close to his chest about the artists they think are on the up, he does share another abstract expressionist tip: Michael West, who was in fact Corinne Michelle West — but fellow artist Arshile Gorky advised her to exhibit under a man’s name to be taken seriously. Arte Collectum has just bought its third West work, her impasto, silvery starburst painting “Dagger of Light” (1951), which goes on loan to Barcelona’s Fundació Joan Miró for Exchanges: Miró and the United States later this year.Other art investment schemes are making their mark, notably Masterworks, which lists the works it buys as individual, SEC-regulated stocks. This has resulted in 450 listings to date, and 23 paintings have been sold, many for seven figures and by the likes of Banksy and Jean-Michel Basquiat. Chief executive Scott Lynn says that Masterworks had $1.1bn in assets under management at the end of 2024 and that he expects to spend $100mn on art this year. The art market’s recently weak performance has “arguably been the best buying opportunity of our lifetimes,” he says, and thinks values in general have started to tick up again. He and Arte Collectum’s Höglund see art’s low correlation with stock markets as an appeal, and while this is an uncertain science, art certainly doesn’t move immediately in step with traditional investments, making it a potential hedge. The art adviser Martina Batovic, founder of Artisan Art Intelligence, finds that art has even proved prophetic. “I have a client in finance who always asks me how the art market is doing, because when things are getting tough, art is often one of the first areas where people take a pause,” she says. Höglund is realistic about art’s value within a wealth management portfolio. “Art is an alternative within alternative assets,” he says, while Nittve says “it’s about value preservation. The art we buy won’t fall as much as a start-up company, it will never go to zero.” It’s not a ringing endorsement but seems enough to keep the art-as-an-investment crowd going.

رائح الآن

rewrite this title in Arabic The surprising rebirth of the art investment fund

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2026 جلوب تايم لاين. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.