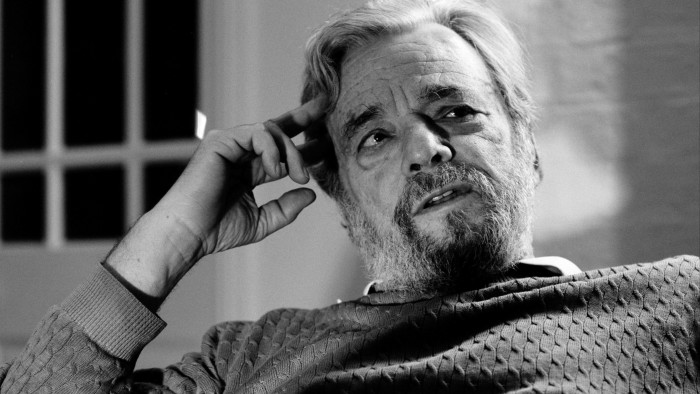

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic Next week, London’s National Theatre will stage Here We Are, the final work by the late Stephen Sondheim, composer of musicals such as Sweeney Todd, Company and Sunday in the Park With George; a man so revered that his nickname among friends and fans was simply “God”. Based on two social satires by Luis Buñuel — both of which take place at bourgeois dinner parties surreally subverted — the idea for Here We Are first came to the film-obsessed Sondheim in 1982. But after starting work on it in earnest in 2013, his exacting standards and advancing age led to a creative block that lasted almost until his death in November 2021. Two years later, the show received its world premiere in New York and now, with a few rewrites and a partly new cast including Martha Plimpton, Rory Kinnear, Jane Krakowski and Denis O’Hare, it comes to the UK. David Ives, book writer: Steve called me up out of the blue in 2009 and invited me for a drink. I didn’t know him very well. He said, “I have an idea for a musical. Would you want to work on it?” What do you say when Shakespeare asks to collaborate? I said yes. We worked on the idea from 2010 into 2013, but eventually had to leave the project behind. Then he told me he had an idea for another project, based on two films by surrealist filmmaker Luis Buñuel, The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie and The Exterminating Angel. I later found out it was actually [director and playwright] James Lapine’s original idea, who had worked with Steve on Into the Woods and Sunday in the Park With George, which they’d discussed first in 1982. I know this because I ran into James and he said, “I hear you’re working on my musical.” We figured out the characters and structure fairly quickly, with the first act Discreet Charm and the second The Exterminating Angel. Within a year we had the basic outline, as it pretty much remains today.Joe Mantello, director: In 2004 I directed a revival of Assassins, which I had to pitch to Steve. When you’re standing outside the door of his house, about to meet this giant of the American theatre, it’s very intimidating. But when you sit down and actually speak to him, it’s quite the opposite. He was an extraordinary collaborator in that he never played the Stephen Sondheim card. Twelve years later, I still don’t know why, I was invited to a reading of what Steve and David had written and asked to direct the show. When that first chord kicked in, I got chills. No one but Steve could have written it.We were all stuck in our homes [during Covid] and one night I said to my partner, ‘Do you think we’ll ever get out?’ and suddenly I thought, ‘This is Act Two’Ives: We would meet in Steve’s study and he would sit or lie on an antique ship-captain’s bed. We knew what many of the numbers were going to be, we knew their shape and which characters would sing them. It was just a matter of writing the songs. But Steve was a master procrastinator. He once claimed he couldn’t do any work because of an ingrown toenail.Mantello: We did a rough staging of Act One with music, then read Act Two. But a couple of years into it he just felt that he couldn’t crack Act Two musically.Ives: Steve was already in his eighties, so he was slowing down. At one point I said, “You know, Verdi wrote Falstaff and Otello when he was older.” Steve’s response was, “I hate Verdi.” But gradually the work was getting better. Then he stopped. He couldn’t write beyond the moment [in The Exterminating Angel] where everyone finds themselves trapped in a room.Mantello: He was having a hard time understanding what they would be singing about. A big part of his process was that content dictates form, and the content seemingly didn’t lend itself to musicalisation.Ives: We were living in a surrealist dream, like something out of a Pirandello play. Working with someone who was supposed to be writing a musical but wasn’t. Our collaboration ended up feeling more like a friendship, and maybe that made it a bit too easy for him not to work. We were opposites in many ways. He worked late at night while I worked in the morning. I hate stage directions, but Steve dictated every nuance. He was so exacting and it was sometimes exasperating.Denis O’Hare, cast member: I met Steve when I did a terrible failed audition for Passion in 1994. He said to me, “Yeah, that’s a really hard song,” which is a nice way of saying, “Boy, you didn’t get that.” Years later, I played Guiteau in Assassins. After a show, he said to me, “Ah, Mr O’Hare, your usual mediocre performance.” It was hard to know if it was a joke. It’s hard to read the man. Ives: Around 2018, I found myself drifting away from theatre. I told Steve, “Maybe it’s time for you to find someone else.” But in late 2019 he called me up and said, “I’d love you to come back and try again.” I couldn’t say no. We picked up right where we left off. Then Covid hit, and everything was on polar ice. In 2021, Joe called me. He said, “I’ve had an epiphany.”It was never intended to be a Broadway show. It’s not a ‘show’ in the traditional sense; it’s a final statement from a great American artistMantello: We were all stuck in our homes and I remember turning to my partner one night before dinner, and saying, “Do you think we’ll ever get out?” and suddenly I thought, “This is Act Two.” We’d never taken seriously the idea that they can’t leave the room. It was always an abstraction. But what if we take what we’re going through right now and feed that into Act Two?Ives: In September 2021, we gathered in a room with a stellar group of actors for a reading. Steve was in great spirits, healthy, walking with a cane, cheerful. Almost Falstaffian. It was the last time I ever saw him.Mantello: The three of us sat down after that reading and had a very serious conversation. I said, “We have to all agree that if you never write another word, this is the piece.” And he agreed.Ives: Two months later, on Thanksgiving 2021, Steve passed away. The show is about a group of rich people trying to find a meal and failing. And here he was, bowing out after dinner with friends on the day that’s all about food. I can just hear him laughing at the poetic irony.Martha Plimpton, cast member: It was so unexpected, because he wasn’t ill. He was old, but still working every day. He still procrastinated, he still stressed. It was really shocking, and I spent the next couple of days just listening to his music.Rufus Norris, outgoing director of London’s National Theatre: After Steve died, his friend and lawyer Rick said to me, “You know, there is another work.” It sounded bonkers. He said, “Sondheim’s favourite theatre in London was the National.” So I said, “Of course, if there’s a way of making it happen, then we will.”Ives: It was never intended to be a Broadway show. This is not a “show” in the traditional sense; it’s a final statement from a great American artist. We opened at the experimental venue The Shed in October 2023.O’Hare: Rehearsals for the New York run were pretty crazy. There was a great deal of rewriting, rearranging, taking things out and putting them back in. The music stayed the same, but [music director] Alex Gemignani was trying to figure out where it all went. The script now is different from the premiere. It’s unlike anything Sondheim has done. It doesn’t have a traditional narrative arcPlimpton: He was like a musical detective piecing things together. The script now is quite different from the premiere at The Shed. It’s very unlike anything that Sondheim has done previously. It doesn’t have a traditional narrative arc.O’Hare: I play five disparate parts, but they’re all working-class people who are overlooked. This piece is super-scary because it’s about the coming revolution. In New York after the show, a woman wearing $3,000 worth of clothes and a purse that was worth the same as my car said, “I love the show, it’s so accurate, such an indictment of these people.” People choose to not see themselves sometimes because they can’t face it.Norris: I remember talking with Steve once and asking what he listened to. He told me about this obscure eastern European radio station. He said, “I listen to it because they never play anything I’ve ever heard. I constantly want to be stimulated.” When others would have been watching the telly and going to bingo, he’s still feeding his brain with new information.Mantello: The most surprising thing about Steve was how hard he was on himself. He wouldn’t settle for repeating something he’d done before, even after all he’d achieved. There will always be the question: would he have written more? But had he been in the room and experienced it as it exists now, he would have been excited.Ives: [Sondheim] was drilled by the press for shows that later became staples. He was his own brand, always new, always smart, always funny. He is his own universe.April 23-June 28, nationaltheatre.org.ukFind out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning

رائح الآن

rewrite this title in Arabic Stephen Sondheim’s last musical — and how it all came together against the odds

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2026 جلوب تايم لاين. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.