Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic Unlock the Editor’s Digest for freeRoula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.A landmark exhibition opening on April 12 at London’s V&A museum will illustrate how the three Cartier brothers drew their inspiration from far and wide, the past and their present.The three were avid travellers and collectors of art books about early civilisations, and this curiosity was to inspire a new style of jewellery. They were the first in modern times, albeit a century ago, to draw on the past to make something fresh and modern, their lush, Mughal-inspired Tutti Frutti jewels being a prime example.Louis Cartier and his designers delved deep in their exploration of other cultures and their history, in order to garner inspiration for their jewellery.Old civilisations have long inspired jewellery designers. In Europe, the jewellery of the Middle Ages was influenced by designs from Byzantium, while styles in eastern Europe reflected jewellery that made its way along the Silk Road during the Renaissance.In the modern world, Dolce & Gabbana’s Alta Gioielleria collections draw on the Renaissance by recreating miniature portraits from the era, using the same techniques. These portraits — of such figures as Italian noblewoman Beatrice D’Este — are then set with jewels and worn as large pendants, much as they would have been during the Renaissance.The brand has incorporated other historical elements in its Greek-inspired high jewellery collection, such as micro-mosaics or authentic Hellenistic coins. The collection is on display until April 2 in the brand’s Du Coeur à la Main exhibition at the Grand Palais in Paris.In Athens, Ilias Lalaounis spent 60 years building a museum showcasing classical Grecian and Byzantium treasures that became the soul of the Lalaounis brand. “The essence of our creations is deeply rooted in ancient Greece, a rich source of inspiration throughout its history, from Neolithic times to the Byzantine era,” says Demetra Lalaounis, director and daughter of the founder. “Living in Greece, inspiration is all around us; we breathe it and live it every day.”Drawing on ancient, handcrafted techniques such as hand-woven filigree and hand-hammered finishes, her sister Maria Lalaounis, the brand’s creative director, experiments with volume and the surface rendering of the gold to create pieces with a modern aesthetic that feel contemporary and are highly wearable.As with Lalaounis, cultural heritage can have a powerful influence on designers: much of the jewellery by Krishna Choudhary of Santi contains gemstone treasures from the family’s archive in Jaipur. He references the 16th- and 17th-century Mughal discipline of design in the geometry and patterns of the metal in which these jewels are set, forming modern heirlooms. “I want to be unconventional, think about how a jewel can be more approachable and subtle, but still have the Mughal soul,” Choudhary says.I want to be unconventional, think about how a jewel can be more approachable and subtle, but still have the Mughal soulFor example, he has an impressively large portrait-cut diamond in what might be considered an industrial-style hexagonal setting for a pendant, but the pattern is Mughal-inspired. He also plays on the use of matt-finished metals, mostly dark titanium with a bit of rose gold, for modernity.“I am always researching about stones, about design, revisiting and reimagining patterns and putting them in a different context in terms of colour, and of positive and negative space, maybe inspired by Mughal architecture and a contemporary art exhibition,” Choudhary says, explaining his ideas for Cartouche-design ruby earrings.The Materials of the Old World collection by Glenn Spiro and his son Joe illustrates the innovative way the pair combine unique stones with ancient artefacts to create strikingly modern jewels. They share a magpie eye for interesting elements, such as the gold Baoulé decoration from west Africa and antique amber jewels suspended on a torque that is a design rooted in classical antiquity.“We work with a lot of generational dealers and families, usually in Europe, but sometimes you have to travel far and wide to find exceptional things,” says Joe Spiro. “We spend an obsessive amount of time sourcing these materials.”A certain playful irreverence to the Spiros’ materials marks their work. “I think when you find juxtapositions between old and new or black and white, the relationship is symbiotic,” says Joe.The idea of using something antique to create a new treasure is not limited to Europe. Hong Kong-based jeweller Austy Lee goes to antique fairs in Japan to forage for elements he can use in his jewellery. Artefacts such as Japanese menuki, shakudo, lacquerware and Satsuma-ware are combined with jewels in modern, exquisitely detailed earrings and brooches.“My habit of collecting antiques stems from the fact that each antique is a fragment of history and culture,” says Lee. “It contains the cultural essences of various ethnic groups and the author’s unique understanding and interpretation of that culture.”He throws himself into studying these subjects and exploring them often leads to bold and innovative ideas for new creations. Thus, from ancient treasures, new heirlooms are born.

rewrite this title in Arabic Past cultures provide rich seam for contemporary jewellers

rewrite this title in Arabic L’opera seria at La Scala, Milan is a farce where the laughs wear thin — review

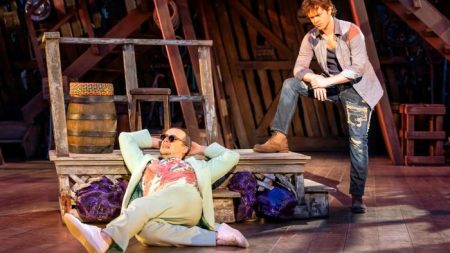

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic Unlock the Editor’s Digest for freeRoula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.During an evening performance at La Scala, things are going badly wrong. The dancers’ camp routine is uncoordinated, a soprano singing from atop a flimsy cut-out elephant shrieks as she tumbles, and other precarious scenic elements — suspended by what must be sheer optimism — come crashing down. An impresario is dragged onstage to announce that the theatre has regrettably collapsed. He then makes a quick getaway, leaving the company to soldier on.The anarchic climax comes in a Milan performance of L’opera seria, Bohemian composer Florian Leopold Gassmann’s riotous 1769 opera for Vienna satirising the conventions of the musical genre at the time. The work, while obscure, resurfaces occasionally, with Brussels and Turin mounting it in the past decade. Now La Scala, in a co-production with the Theater an der Wien, has staged it for the first time. It has enlisted French director Laurent Pelly, a master of organised chaos, for the occasion. The plot is simple: Fallito, a bankrupt impresario, mounts a new opera, but rehearsals unravel as librettist and composer bicker and sopranos claw at each other. The near sellout La Scala audience — perhaps lured by its strong recent revivals of rarities such as Cavalli’s La Calisto and Cesti’s L’Orontea — was in stitches by the time the opera-within-an-opera, set in Mughal India, literally fell apart. It is to La Scala’s credit that one of the world’s more formal theatres is willing to laugh at itself.And yet, at the risk of sounding curmudgeonly, this critic found the three-and-a-half-hour performance (intervals included) tiresome. There is only so much unadulterated slapstick one can take.The main issue is the opera itself, with Ranieri de’ Calzabigi’s libretto offering scant depth or interest beyond unending farce and Gassmann’s score — though engaging — lacking memorable set pieces. Pelly’s duochrome production did not help. Lurking stagehands in black observe rehearsals from the shadows, seemingly waiting to depose their employer, and singers wearing white period costumes and zanily coiffed wigs keep things in constant motion as they enter a raked wooden stage via a series of doors. More onstage colour and scenic variety might have broken up the monotony.The performance was buoyed by a well-chosen cast. Pietro Spagnoli was drolly self-serving as the increasingly beleaguered impresario, who eventually abandons the theatre like a captain fleeing a sinking ship. Mattia Olivieri and Giovanni Sala shone as the haughty poet Delirio and the lusty composer Sospiro, and tenor Josh Lovell’s error-prone Ritornello — the opera’s self-absorbed castrato — avoided mishap in testing vocal acrobatics. The trio of rival sopranos — Julie Fuchs’s seething Stonatrilla, Andrea Carroll’s melodramatic Smorfiosa and Serena Gamberoni’s kittenish Porporina — were boldly characterised. Their boastful mothers, headed by countertenor Lawrence Zazzo, provided pantomime horseplay.Conductor Christophe Rousset propelled a spirited rendition of the scuttling score, with baroque outfit Les Talens Lyriques, interspersed with La Scala’s regular players on period instruments, vividly relaying Gassmann’s dizzying harmonic transmogrifications. An evening of easy laughs, but one can’t help but wonder if La Scala — a house currently at the heart of Italy’s belated early opera revival — might have dedicated precious programming space to a more worthwhile masterpiece long overdue its Milan premiere.★★★☆☆To April 9, teatroallascala.org

مقالات ذات صلة

rewrite this title in Arabic Theatre review: The Women of Llanrumney, Stratford East — a searing interrogation of slavery

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic Unlock the Editor’s Digest for freeRoula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.The Women of Llanrumney sounds like a tale from the Welsh valleys — and in a sense it is. Azuka Oforka’s blistering first play focuses on a grim episode in Welsh history: involvement in the transatlantic slave trade. Sharp and shocking, Oforka’s script fuses fictional characters with real events to powerful and resonant effect. Not all the stylistic jumps from horror to comedy work, but it’s still an impressive debut.We’re in the “Great House” on the Llanrumney plantation, St Mary Parish, Jamaica, on the eve of the 1765 Blackwall’s revolt. The owner here is Elisabeth Morgan. A relative of the previous owner, Sir Henry Morgan (she is imagined, he and the plantation are not), she has run herself into debt through drinking, gambling and general high living, failing to notice that the sugar crop is blighted. Now she is suddenly faced with ruin.As she scrabbles to save herself, we watch through the eyes of two women whose lives depend on her decisions but who have no say in the matter: Annie, an enslaved woman who has worked her way up to housekeeper and hopes that, by getting close to her mistress, she can gain her freedom; and Cerys, Annie’s pregnant daughter, newly promoted to the household and therefore vividly aware of the brutalities of the cane fields.While they polish silver and wheel great platters of food around, the two enslaved women talk passionately of freedom. “Freedom can’t be handed on from one person to another on no piece of paper,” says Cerys, arguing for rebellion. But Annie, who knows from bitter personal experience how slave-masters punish those who rise up against them, can’t let herself dream of resistance. Meanwhile, Elisabeth is soon brought up hard against the limits of her own autonomy, as various men name their grubby price for getting her out of financial catastrophe.Oforka weaves the idea of freedom through the play, introducing characters with differing levels of agency and illustrating the multiple examples of inhumanity in an abhorrent system built on exploitation. But while the rules of patriarchy and capitalism trap some of the white characters, it is, of course, the Black people who are grotesquely abused. The play bristles with terrible (true) stories of hideous violence and vicious cruelty. It’s hard to hear, but necessary, and Oforka reminds us that we live with the legacy of that system.In Patricia Logue’s nimble production (first seen at Cardiff’s Sherman Theatre), the well-appointed dining room (precisely designed by Stella-Jane Odoemelam) becomes a pressure-cooker. Matthew Gravelle adroitly portrays three differing sorts of predatory men, while Nia Roberts plays Elisabeth as a cracked belle, a shrill, larger-than-life version of a period dramatic heroine. This mostly works well, though at the end, her callous disregard for Annie and Cerys might have more chilling power if delivered in a lower key. The stage belongs, however, to Suzanne Packer’s Annie, all bright, busy, desperate energy, and Shvorne Marks’s Cerys, still, watchful and raging. This is, rightly, their story.★★★★☆To April 12, stratfordeast.com

مقالات ذات صلة

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.