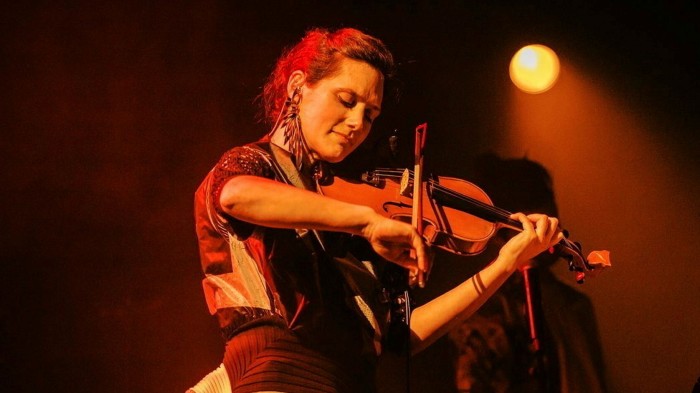

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic The first time I saw Rakhi Singh, she was barefoot, playing the violin at the Purcell Room on London’s Southbank. Singh was leading Manchester Collective, the flexible group of classical musicians she co-founded, in a concert of Oliver Leith, Caroline Shaw and Shostakovich. The Shaw was transfixing, the Shostakovich fearsome and Singh, who spoke to the audience before each piece, in gentle command.It would have been much riskier being barefoot at the outset of Manchester Collective’s existence. Founded in 2016 with her friend Adam Szabo, the group put on concerts in artists’ spaces, clubs and warehouses, “cold and dark and damp”, says Singh when we meet in south-east London. “I remember some of the early shows playing with my coat and hat on. I couldn’t wear a scarf because you can’t really when you’re a violinist. I had as many layers of clothes on as I could.”The strategy was partly a necessity — no polished venue would take a brand-new ensemble — but also a choice to enable creativity, a way of doing classical music differently. “There’s something rather curious about when you play something out of its normal context,” says Singh, 43. “When you juxtapose things, it creates a certain energy. People were quite curious to come and see a classical music concert and be able to drink a beer at the same time . . . We got rid of all the formalities and I think there was a thirst and a hunger for that.” It feels “electric”.The concerts’ slick underground branding and outré locations did attract an untraditional audience. In an early concert in a former abandoned mill, says Singh, one ticket-holder walked in and exclaimed, “They’ve got violins?!”Since those days, Manchester Collective has entered the mainstream, playing concerts at the Southbank Centre and Wigmore Hall, and winning the Ensemble prize at the Royal Philharmonic Society awards. But it has kept a spirit of adventure too, with a spotlit gig in a Shoreditch club and, at the end of April, a two-date tour for Refractions, a “continuous aural and visual experience” mixing contemporary dance and classical and experimental music.Singh’s musical training did not make her an obvious candidate for sidestepping classical niceties. Born in south Wales to an Indian father and English mother, she won performance prizes as a teenager and attended the Royal Northern College of Music, before leading the Barbirolli string quartet and guest-leading top UK orchestras. But she felt restricted by traditional curricula and concert programming: “As valuable and as interesting as it is to study Haydn and Beethoven quartets and Brahms symphonies and the Bartók quartets, there is still much more music to be explored.”Having enjoyed success young, her career “fizzled out after a while”, which reinforced the impetus “to put on some gigs . . . to play the music we want to play”. That included commissioning works from composers for a fresh stream of what today sounded like, so Manchester Collective has given numerous world premieres from people such as Laurence Osborn.The ensemble has an unusual accordion-like quality — it can expand depending on the sounds needed. In the Purcell Room concert, there were 18 musicians on stage, but at Village Underground in east London last summer it was just violin, viola and cello for Imogen Holst and Errollyn Wallen, the audience on four sides around a small stage and the musicians occasionally popping up behind or beside us. The only constant is Singh herself, both as musician and underpinning sensibility.When she conceives concerts, it is not nearly as simple as the overture-concerto-symphony formula that orchestras hew to. “Our programmes really are chalk and cheese sometimes — or yin and yang, maybe I should say . . . I don’t shy away from putting things in that I actually know some people won’t like,” Singh says. “But then I’ll make sure that there’s something counter to that. So everyone gains something new and it’s not a bad thing to be uncomfortable sometimes, it’s important.”Refractions will involve another level of complexity from previous Manchester Collective endeavours, with 12 strings and a piano traversing a millennium of music as dancers, choreographed by Melanie Lane, interpret it on stage. The newest end will be picked up by electronic musician Clark. Music of any era, for Singh, is communication. “When I relate to a piece of Hildegard von Bingen [a 12th-century female composer], I feel like I’m getting a message from the past and living through it in the present,” she says. That is why it all belongs together: “It’ll dip from Hildegard von Bingen to techno, back to Bach, back to more almost cinematic sci-fi soundscapes, back to Beethoven.”Singh has long experimented with multimedia, interdisciplinary performances, so she says Refractions is the culmination of a decade’s work. It fits well into the modern movement where musicians and groups, such as Elaine Mitchener and Bastard Assignments, dissolve the boundaries between music, theatre, film, performance and visual art.This amorphousness makes it hard to talk about. “I feel like a bit like Michelangelo making ‘David’ — he can see the thing inside the stone. But until it’s all carved away, it’s very hard to describe it,” Singh says. Nevertheless, it will have electronica and baroque dances, and an arc from “chaos and destruction [to] reflection and restoration and then ecstasy”.It’s best to end with ecstasy, I say. Singh laughs: “It’s always nice to go out on a high.”‘Refractions’ is at Bridgewater Hall, Manchester, on April 25 and the Southbank Centre, London, on April 26, manchestercollective.co.ukFind out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning

رائح الآن

rewrite this title in Arabic Meet Rakhi Singh — the time-travelling violinist bringing together baroque and techno

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2026 جلوب تايم لاين. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.