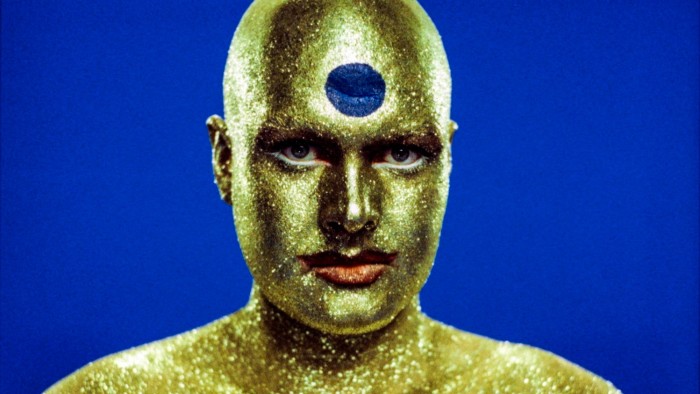

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic When does art become art, if the artist doesn’t self-declare as an artist? Leigh Bowery lived a life of constant performance, collaboration and provocation, rooted in nightlife. The Australian became known for his extreme, body-morphing looks, mostly made by himself on a shoestring. He was personable, funny, talented, restless, fabulous and broke. Bowery arrived in the UK aged 19 in 1980, lured from the Melbourne suburb of Sunshine by London’s punk scene. He was active in the city for just 14 years until his death at 33 from Aids-related causes. In that time, he became one of the most influential figures in late 20th-century global counterculture, working across art, fashion, music and dance.His life, work and impact are about to be celebrated with a major exhibition at Tate Modern. And yet Bowery himself did not exactly fit into the art world. “He refused the human tendency to define things,” says Fiontán Moran, the show’s curator. “He would say, ‘if you label me, you negate me’.”Tall and imposing, Bowery made garments and outfits that exaggerated his frame and taunted propriety. He had studied fashion in Melbourne, yet fashion itself bored him — he had no patience for the behind-the-scenes production and sales needed to run a label. His garments were usually one-offs, at first fantastical subversions of jackets and dresses in shocking colours, designs that became increasingly more otherworldly and extreme. He wore what he made to clubs such as Cha Cha’s, below Charing Cross Station and his own night, Taboo, on Leicester Square. In 1983, he began making costumes for choreographer Michael Clark, eventually joining the company as a performer himself. The garments cut against presumptions of dress as much as Clark’s choreography did against the traditions of ballet. A leotard with the buttocks cut out; a dancing teapot; a skullcap with lightbulbs attached: his ideas were like electric shocks, but the garments were always immaculately made, amplifying the movement of the dancer.Bowery was staging performances in an art context as early as 1984, at an event held in a church crypt organised by an artist collective, the Neo Naturists. That same year he was the subject of a work by British artist Stephen Willats, now in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery, expressing Bowery’s character through a collage of photos, cosmetics and other artefacts.This set the path for the next 10 years, of making work and appearing in the work of others, including, most famously, in portraits painted by Lucian Freud. Bowery did so without playing the art world game: he was never represented by a gallery, and didn’t produce art objects to sell. Bowery’s practice was in stark contrast to a sudden arch commercialism among other young artists at the time, led by a student named Damien Hirst. His 1988 group exhibition Freeze, said to be the beginning of the YBA movement, was sponsored by property developers Olympia & York. By the birth of the YBA movement, it was seven years into the Aids pandemic. Aids killed possibility: we cannot know what would have been made by those whose lives were cut short. Bowery’s practice, of making without conforming to labels, had a lineage in punk and queer alternative lifestyles of the 1970s. By looking at his output, before his own life was lost to Aids, we can consider ways in which art-making could have evolved. Because, of course, being inspired by Bowery does not necessarily mean emulating Bowery. My first memory of Leigh Bowery is from the January 1987 issue of The Face. I was 12 and had been buying the magazine for a few months. It featured a story on Trojan, Bowery’s sometime flatmate and, briefly, boyfriend, but it was Bowery who jumped out at me, the whirl of this world that encapsulated nightlife, performance, art and pleasure. I wanted to be in it. It was the realisation that anyone could turn up and take part, if they had something to contribute.“They were just making things and were not thinking about its legacy or impact,” says Moran. “When you have meagre funds, anything you do is a miracle in a way, because you’re creating art out of nothing. It’s only in time that we see the significance.”With Bowery, that moment is now. For the past few months, many of his garments have been on show at Outlaws: Fashion Renegades of 80s London, an excellent exhibition at London’s Fashion Textile Museum. A biography by Bowery’s friend Sue Tilley, Leigh Bowery: The Life and Times of an Icon, has just been republished. And Leigh Bowery! at the Tate Modern will place him fully in an art context. Bowery’s work asks us to accept the seriousness of what seems frivolous. In a 1988 appearance on the BBC’s The Clothes Show, he modelled seven of his sequinned dresses, each with a full face-covering mask, during afternoon tea in The Georgian restaurant at Harrods. The clip is hilarious but also stark, Bowery versus the strait-laced world. It was the year that the UK government introduced Section 28, prohibiting local authorities from “promoting” or “teaching” homosexuality. It was also the year Bowery discovered he was HIV-positive, a diagnosis he kept secret. That same year, Bowery participated in a week-long residency at the Anthony d’Offay Gallery in London. Each afternoon, he would perform behind a one-way mirror, striking poses on or around a chaise longue, a different outfit each day. Street noises were piped into the space, as well as different smells each day — banana or marshmallow. The artist Cerith Wyn Evans filmed each performance. One day, he brought with him his friend Lucian Freud, whom Bowery had already met one night at Taboo. Six of Freud’s subsequent portraits of Bowery will be in the Tate show. Bowery meant so much to Freud that, when he died, Freud paid for his body to be shipped back to Australia, so he could be buried next to his mother.Meanwhile, Bowery’s work became more focused, more extreme. In 1992, he debuted his “Birth” performance at the London club night Kinky Gerlinky. Bowery appeared onstage in a striped stretch cotton dress, his body padded below to form an extreme stomach. He was wearing a harness, into which was strapped his collaborator and eventual wife, Nicola Rainbird. He lay on his back, writhed as if in pain, then Rainbird emerged naked, in body paint as if covered in blood. Bowery would cut a cord attaching them, then carry her as if a newborn.They performed the routine often, at the Wigstock festival in New York or with Bowery’s band Minty. The documentation of Bowery’s work, as seen at Tate, allows us to clearly place him within the context of international performance art. His brilliance came from breaking boundaries. “He was not scared of trying anything,” says Moran. “That’s what makes Bowery exciting to look at, because it’s very much about living your fullest life, and embracing everything that’s on offer, without being too concerned about what it means, how it can be sold or how it can be marketed. He was completely uninhibited.” It’s a lesson that many young artists, caught in the trap of a faltering art market, could heed today.February 27-August 31, tate.org.uk. Charlie Porter’s novel ‘Nova Scotia House’ (Particular Books) is published on March 20Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning

رائح الآن

rewrite this title in Arabic Leigh Bowery defied the art world — now he’s its darling

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2026 جلوب تايم لاين. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.