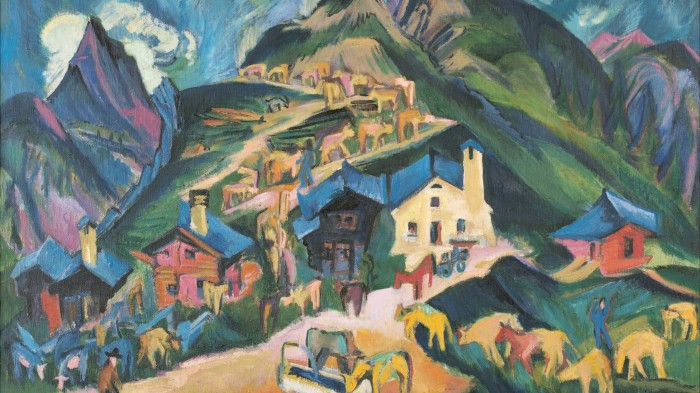

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic It is midnight on January 1 1925, and a trio of young idealists in Obino, a hamlet in Switzerland’s southern Ticino region, look out on snowy slopes drenched in their imagination in brilliant visionary colours. They toast the new year by founding an art movement, the Rot-Blau Gruppe (Red Blue Group). Their inspiration is a strange, sick, morphine-addicted German painter in another Swiss mountain village, Davos. Dismissed from war service to recover in Davos’s sanatorium in 1917, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner began transmuting the hectic urban expressionism of his shrill Berlin scenes to hallucinatory Alpine landscapes in glowing unnatural pinks and violets. For a brief moment — Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, set in Davos, appeared in November 1924 — this rural backwater where motor vehicles were still banned became a centre for the German avant garde. It’s a fantastical tale, hardly known, and wonderfully told in a small, riveting centennial exhibition Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and the Artists of the Rot-Blau Group at Lugano’s Museo d’arte.There emerge the distinctive personalities of Hermann Scherer, originally a stone mason, Albert Müller, trained as a glass painter, and architect Paul Camenisch, as under Kirchner’s spell they created a distinct Swiss expressionism of the mountains. Kircher in turn recalibrated Berlin modernism’s prewar frenzy — harsh lines, violent chromatic contrasts, jauntily distorted perspectives — to depict the ancient rhythms of peasant life as anything but peaceful. A farmer’s wagon with bright yellow wheels and red horses hurtles across the canvas in “Chariot and Horses with Three Farmers”. The slow ritual of a parade of cattle climbing to the summit becomes in “Ascent to the Alpine Pastures” a feverish scene played out in the shadow of cloud-swirled magenta crags.Rising at the exhibition entrance are the peaks of Kirchner’s “Tinzenhorn” beneath a moonlit emerald sky: jagged purple-crimson ridges, a little church in the valley, every feature exaggeratedly angular. The luminosity evokes the clear, crisp mountain air, and as Kirchner explained, “the changes in form and proportions are not arbitrary, but rather serve . . . the mental expression”. The painting celebrates nature’s restorative power yet reflects the artist’s instability: between elation at his new surroundings, and the anguished effects of a breakdown during the first world war. Such dissonant landscapes, aggressively vertical, fraught with danger, dominate a vertiginous show. “The Ravine” is impassable, rushing headlong at the viewer, its slopes studded with pines as spiky and defiant as Kirchner’s feather-hatted Berlin streetwalkers. Wildly coloured, slanting bare trunks shine in the dark wood in “Landscape in a Forest with Stream”.Kirchner’s trees are recalled in the twisting tendrils and gnarled features in Camenisch’s self-portrait “Man in the Vines”, the torrent in his “Male Nude”, a huge wide-eyed figure about to bathe in a fast-coursing stream in an almost psychedelic scene. Müller’s more lyrical “Resting Woman” reclines in an abstracted wooded landscape patterned in black lattice work with pink touches, reminiscent of stained glass. The earliest painting, “Alpine Kitchen” (1918), from Madrid’s Thyssen-Bornemisza collection, records Kirchner’s initial home, a simple hut in the Stafelalp, and also his emotional state on arrival. In spiralling distortions, warm lemon, orange and rose walls and floors, swaying cupboards and beams, spin around a lone hunched figure with elongated nervy fingers, a self-portrait. Unlike Kirchner’s Berlin interiors, focused on powerful characters, here the surroundings overwhelm the downcast figure.“In Davos I found an emaciated man with a piercing feverish gaze who seemed to observe the approach of death,” wrote Henry van de Velde on first visiting Kirchner. But the painting carries hope: the tilting perspectives lead the eye to the wooden door, open to the Tinzenhorn, the vanishing point of the whole composition — giving a sense of air and freedom.All this looks superb at the Museo d’arte, whose dramatic main gallery fronted by an enormous window on the lake and mountains pulls landscape into the interior as Kirchner often does. In “Farmer with Child (Fairytale Teller)” the pair are illumined by a glistening snowscape outside the window, its light echoed in two white coffee cups — the mood as otherworldly as a fairytale. In deep pinks and purples, “Before Sunrise” depicts Kirchner and his partner Erna Schilling, fashionably dressed with bobbed haircuts, on their terrace; blue hills and pink trees surge towards them, Kirchner’s rough wood carvings of Adam and Eve loom above. Inevitably this Gauguin of the mountains enchanted Swiss painters. Kirchner hosted the three Rot-Blaus in Davos and arranged their exhibition in Dresden in 1926. A self-portrait with Müller, faces dabbed in green paint, from the journey there, “In the Train (Albert Müller and Kirchner)”, sold at Sotheby’s in November for $1.08mn (not in the show), attests to their camaraderie.There is not enough Müller in Lugano’s exhibition, but Scherer triumphs: in the hot red, burnt umber and acid green of “Ticino Landscape”’s stylised, tumbling patchwork of peaks, slope and plateaus and in his “Self-portrait” as an outsize wanderer, precariously leaning back into a multicoloured village. The figure has the hulking proportions and raw finish of the wooden sculptures which Kirchner taught him.In The Magic Mountain the guests get ill rather than cured by their Alpine sanctuary, and something similar decimated the Rot-Blaus. After two years of frantic work, Müller died at 29 from typhus in December 1926; Scherer died in 1927. Camenisch, sole survivor, founded Rot Blau II in 1928 with Max Sulzbachner; the latter’s arresting “The Globetrotter”, an elderly figure on the edge of a vermilion path through a forest of twisting scarlet trees, was painted aged 21, a homage to Kirchner. Sulzbachner’s continued impact as a conduit of Swiss expressionism was as a Basel mask-maker and popular theatre designer.Kirchner remained in Davos, and portraits such as the conspiratorial “Italian Railway Workers” — building the Rhaetian mountain track, begun in Davos — in capes and fancy hats, faces half obscured by the smoke from their pipes, a miniature train in the background, imply his sympathetic relationship with the community. So does the monumental quartet of individualised grotesques, full of pathos, determination, resilience, in “Lunch of the Farmers”. Bought in 1923 for Hamburg’s Kunsthalle, this was confiscated by the Nazis and displayed in the 1937 “Decadent Art” exhibition, an example of Kirchner’s caricature of supposedly harmonious Volk values. There is nothing harmonious about this compelling show. Kirchner aimed to create a specifically German art, looking back to Gothic’s extreme linear expressiveness; now Germany banned him. He died by suicide in Davos in 1938, fearing a second world war.Emerging from the first one, he had written: “I am still trying to put my thoughts in order and, from all the confusion, create an image of the times, which is my task, after all”. In his mountain refuge, he did so magnificently.To March 23, masilugano.ch

رائح الآن

rewrite this title in Arabic Kirchner and the birth of Swiss mountain expressionism

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2026 جلوب تايم لاين. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.