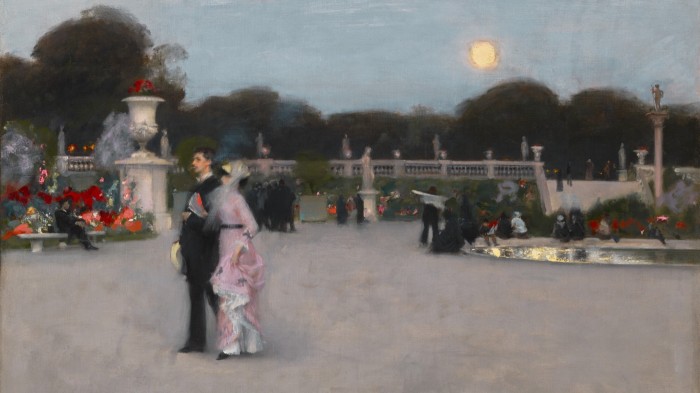

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic The 18-year-old wunderkind John Singer Sargent swept into Paris in 1874 on a powerful gust of talent. The boy showed up at the studio of the fashionable teacher Carolus-Duran and unpacked a portfolio that portended any number of brilliant artistic careers. “I can see the slim youth . . . his arms entwined around a formidable roll of studies which, when disclosed to the eyes of the master, caused him to exclaim, ‘You have studied much,’” a student later recalled. “It might have been said of him . . . ‘He had a splendid past behind him.’”Guided by Carolus-Duran and excited by his own copies and experiments, Sargent promised to grow into one of the age’s greatest landscapists — or academic virtuosos or impressionists or seekers of exoticism or painters of psychologically fraught domestic scenes. He looked backward to old masters without losing himself in nostalgia, and forward to young modernists, while remaining aloof from radical programmes. Whatever he aspired to, he did, magnificently.Sargent and Paris, the Met’s spectacular show captures that sense of explosive possibility. It chronicles Sargent’s decade in the city, when his horizon simultaneously expanded and narrowed. He tried everything, then focused on portraits, which was where the money was.Born in Florence in 1856, Sargent lived an itinerant existence with his American family, flitting, according to season and whim, to Nice, Paris, Milan, London, Salzburg, and Genoa. Only at 20 did he first visit his parents’ homeland, the United States.Just as he straddled tradition and modernity, Sargent blended sensual brilliance with psychological depthThe constant in his peripatetic childhood was sketching. Sargent’s mother, an avid amateur, insisted that each of her three children produce at least one drawing a day. (In July, the Met will present 26 never-seen watercolours by John’s sister Emily.) The family immersed itself in the culture of each place, touring museums and monuments, mingling with living artists, and copying dead ones.Polyglot, worldly, sociable, and confident, Sargent used Paris as a base more than a home. Though he lived in the city that Walter Benjamin later called “the capital of the 19th century”, he had little interest in its teeming new boulevards, its steaming railroad stations, or the bright crowds at the café-concerts. He preferred the alleys of Capri or the dusky backstreets of Venice, timeless screens on which to project his contemporary sophistication.The year after he enrolled in the École des Beaux-Arts, he painted “Wineglasses,” an unpeopled, sun-dappled rural patio in summer where you can practically hear the laughter just outside the frame. Before the end of the decade, he had bottled the wild energy of a girl dancing on an island rooftop, the ferocity of Atlantic waves, the sensual violence of sunlight in Morocco, and the moodiness of a grey day on the Grand Canal. In “The Spanish Dance”, a flamenco performer’s pale bare arms shoot out into black night.And yet despite his frequent escapes, Paris — its social life and gaslit glare, its sheer concentration of artistic inventiveness — nourished his creativity until he abandoned it for London in 1886. He out-Degased Degas in his “Rehearsal of the Pasdeloup Orchestra at the Cirque d’Hiver” (1879) where the agitated brushstroke vibrates like a kettledrum’s skin. “In the Luxembourg Garden” captures a more subdued but still intense mood, a man’s lit cigarette echoing the moon that glows over the flat expanse of gravel.The show’s curator, Stephanie Herdrich, expertly traces how Sargent swerved, then swerved again, honing his craft and sensibility. He matched technique to content, even within a single canvas. In “Dr Pozzi at Home”, an 1881 full-length portrait of a young surgeon, he slides from the smooth enamelled gloss of the face to the statuesque mass beneath a scarlet bathrobe, to a brushy froth of white linen at the neck and cuffs. He edges further towards abstraction in “Ramon Subercaseaux in a Gondola”, depicting his friend in a patchwork of mottled blacks, shades of orange, and dazzling glints on water.Carolus nudged his protégé to revisit the past, especially Velázquez and Hals. The lesson took hold. You can see Hals’ influence in Sargent’s double portrait of François Flameng and Paul Helleu, where he freezes animation with just a trace of blur around the moustache. His 1882 masterpiece “The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit” mirrors the psychological and spatial complexities of Velasquez’s “Las Meninas”, as well as his rippling impasto. Sargent deploys sketchiness strategically, rendering some faces in detail yet leaving unfinished swaths swirling around a void.The two youngest girls open their gazes to the painter; a third sister lurks suspiciously at the edge of the gloom that has all but swallowed the fourth. Sargent respects their reticence even as he puts them on display. The result juxtaposes Victorian innocence with dark Freudian undercurrents. There’s nothing cloying about these kids.Sargent understood children and refused to romanticise them. In an 1881 double portrait, a Parisian boy and his little sister (offspring of the essayist and playwright Edouard Pailleron) perch on a divan against a sunset-coloured ground. The girl stares at the viewer with hostility; critics remarked on her “childish defiance”. Her brother leans forward with bored belligerence and barely concealed contempt. It’s hard to detect any trace of feeling between the two.Just as he straddled tradition and modernity, Sargent blended sensual brilliance with psychological depth. “Madame Paul Escudier” fades into the gloom beside an open window, while sunlight falls through a whipped-cream curtain and on to the velvety blue of her dress. The subject herself almost melts into the buttery brushwork, so that she becomes at once seductive and demure, beseeching yet private.A flock of different Sargents — the connoisseur of fashion, the astute anthropologist, the student of ancient sculpture and Italian Renaissance technique, the bold adventurer — converge in “Madame X”. He saw in Virginie Gautreau’s mermaid-like form and purplish pallor an emblem of Gilded Age decadence. She created herself through make-up and costume, and a display of studies demonstrates how hard Sargent worked to intensify the artifice. Her neck was slender, but not that slender, her profile not quite as knife-edged as he made it.Viewers at the 1884 Salon gawped at this alluring and sinister figure, whose theatricality — not to mention her décolletage — provoked a scandal. He left Paris in part to escape a suddenly double-edged reputation and rebuild a less risqué business in London. But “Madame X” continued to fascinate. Years later, after Sargent’s death, his friend Vernon Lee (aka Violet Paget) wrote admiringly of his predilection for “the bizarre and outlandish,” a taste he shared with Baudelaire. Sargent, she wrote, “tends to the love of all sorts of decaying art, openly approving of the faisandé, ie putrid”. It’s the miracle of his genius, and of the show, that this whiff of rot mixes so easily with the enduring freshness of his eye.To August 3, metmuseum.org

رائح الآن

rewrite this title in Arabic John Singer Sargent in Paris — how the city shaped a prodigious talent

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2026 جلوب تايم لاين. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.