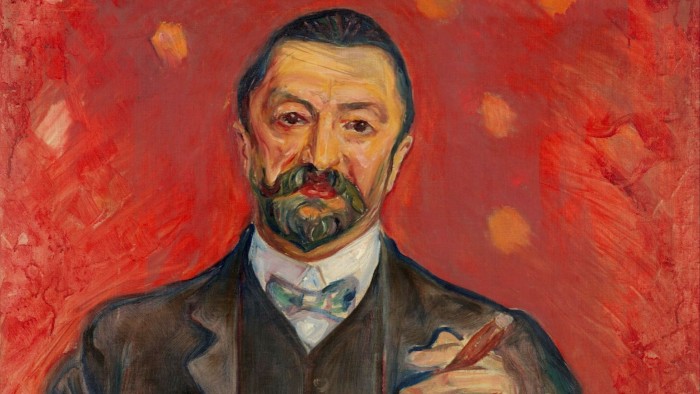

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic Edvard Munch learnt quickly that “when I paint a person his enemies always find the portrait a good likeness. He himself believes, however, that all the other portraits are good likenesses except the one of himself.” For all the pleasures of passionate eloquence and radiant colour in the National Portrait Gallery’s new exhibition Edvard Munch Portraits, you see why few of his subjects cared for Munch’s depictions. His essential idea that personality is a battleground, created by conflicting desires and repressions, pours into each painting and makes everyone appear troubled or awkward. Portraying “my glorious hero”, his friend and Dagbladet’s supportive art critic Jappe Nilssen, Munch painted a towering, glumly earnest figure in expensive purple, against slashing animated green strokes. Nilssen hated it: “He has given full rein to his vicious side and could easily have painted a more beautiful portrait.” The longer you look, the more unnerving the picture becomes, the wild marks around the luxurious attire cohering into a menacing shadow. As relentless is a double portrait of the writer with his doctor, “Lucien Dedichen and Jappe Nilssen”. The sinuous, tall medic hovers gravely over the seated, defeated, now grey and furrowed Nilssen. This was nicknamed “The Death Sentence”.Munch’s own doctor, psychiatrist Daniel Jacobson, who strutted “like a pope” among his neurotic patients, was rewarded with a portrait, legs apart, arms akimbo, subsumed in flames. “Big and dominant in a fire with all the colours of hell,” Munch gloated. Jacobson thought it “stark raving mad”. August Strindberg, appalled at his massive heavy head, fierce gaze and demonic air, exclaimed: “To hell with likeness! It should be a stylised portrait of a poet. Like the ones of Goethe!” When Munch made another attempt, Strindberg threatened to kill him. Politician Walther Rathenau, however, got the point. Confronted with his powerful presence as a life-size silken black silhouette with shiny patent shoes, grasping a cigar whose smoke becomes decorative yellow twirls, he joked: “Awful character isn’t he? That’s what you get for having your portrait done by a great artist — you look more like yourself than you really are.”That extreme psychological truth was what Munch sought, both by depicting people as individuals and, in his 1890s symbolist pictures “The Scream”, “Vampire” and “Melancholy”, making them icons of intense emotion. He wanted to paint “living people who breathe, feel, suffer and love. People should understand the holy quality about them and bare their heads before them as if in a church.” Women mostly became femmes fatales — from the high-contrast lithograph “The Brooch”, vampish violinist Eva Mudocci with cascading hair and pale face in 1902, to “Seated Model on the Couch” (1924), Birgit Prestoe, whom Munch called his “Gothic Girl”, rendered in his dilute, thin late manner. Straightforward female portraits here are weakly generic, apart from his beloved sisters in the summer seaside pair “Evening” — manic depressive Laura Munch, staring vacantly yet intently, lonely in a twilit fjord landscape — and the exalted “Inger in Sunshine”, squinting at the light. The exhibition’s pulse, therefore, comes from charismatic, complex men, beginning with Munch himself: the full-frontal “Self-Portrait” at 19, expression haughty but vulnerable, face half shadowed, half in brilliant light, and the innovative lithograph; “Self-Portrait with Skeleton Arm”, with disembodied head emerging from pitch darkness, a gleaming white bone in the foreground seeming to be the artist’s arm. Both imply a figure caught between life and death. From a childhood marked by the loss of his mother and sister, Munch explained: “As long as I can remember I have suffered from a deep feeling of anxiety . . . I always find myself drawn inexorably back towards the chasm’s edge, and there I shall walk until the day I finally fall in to the abyss.” A trio of sensitive early portraits, 1885-86, are perhaps alter egos. Fellow painter “Jørgen Sørensen”, head angled downward, carved from light that isolates him in a black void, is brooding, introspective. “Karl Jensen-Hjell” is a nonchalant, sickly artist-dandy, desperate to enjoy bohemian life though ill with tuberculosis. “Andreas Munch Studying Anatomy”, the artist’s brother eyed mockingly by a luminous skull, suggests similar fragility. All three men died young. From these sombre works, 20th-century Munch leaps into modernity: expressive and decorative colour, bright detached strokes giving verve and vitality, dashing painterliness offsetting the sober cast of characters. Living in Paris and Berlin, he absorbed the impact of Van Gogh especially: the stunning opening to this section, Jena physicist “Felix Auerbach”, comes from Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum and follows the Dutch master in its empathetic charge, emphatic outlines, asymmetry and sonorous orange-red background. Auerbach stands out majestic and serious. Expanding that monumentality, Munch’s tour de force between 1904-09 is a sequence of glorious, full-length, life-size male portraits, their sweep here unfortunately interrupted by a freestanding wall jutting between them. Munch the psychologist of unease appropriating the swagger of Sargent or Velázquez. The first, gentle Lübeck ophthalmologist “Max Linde”, looks as if he can’t flee the picture fast enough. In large black overcoat, holding hat and cane, he is about to walk out to face the world, reluctantly, steadfastly: a nervy bourgeois straight from Thomas Mann’s Buddenbrooks. His neighbour, Hamburg-Stockholm banker “Ernest Thiel”, stiff, arms crossed defensively, is shadowed by the outline of an eerie stoop-backed figure. This unfinished canvas so disturbed Munch that to Thiel’s shock “he suddenly put his fist straight through it, and sent the easel dancing across the floor.” With short-tempered artist “Ludvig Karsten”, Munch came to physical blows on Midsummer Eve 1905, when painting him, with mixed hostility/affection, as a flamboyant flâneur in a white suit against a dazzling yellow wall, smiling roguishly, “always ready for some sarcasm”. The group concludes with the exceptional portrait of economist “Christian Gierlöff” in 1909, the year Munch, recovering from a breakdown, left Europe’s capitals to “let the molecules settle down after all my inner turmoil” in his new home, peaceful Kragerø. A sliver of its harbour and sea is glimpsed behind the steep rock face, which bears down on Gierloff without crushing him. Blue dabs around his balding head suggest both perilous tumbling stones and a halo. Flurried mauve, turquoise, white, loose strokes, drips, streaks, rain down the picture; Gierloff’s hat, held in an open gesture, is an impasto lemon-blue vortex. Amid instability, Gierloff stands assured in his dashing yellow coat, looking outward. The seascape and free facture herald Munch’s later career as a fluid northern landscapist rather than primarily a figure painter. If there is an element of self-portraiture in every work here, this is a happy place to leave him.March 13-June 15, npg.org.ukFind out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning

rewrite this title in Arabic How Munch’s portraits provoked horror, a fist fight and a death threat

مقالات ذات صلة

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2025 جلوب تايم لاين. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.