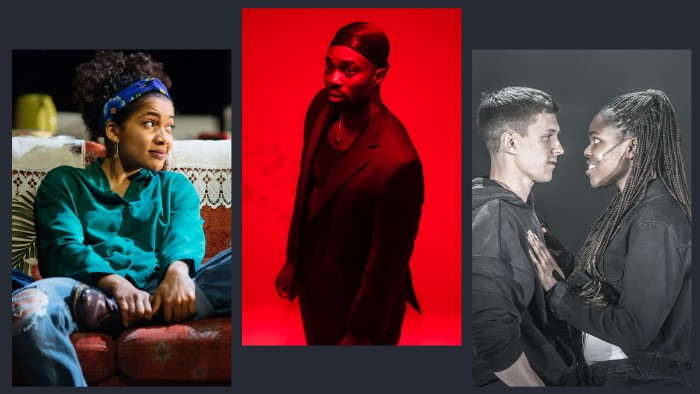

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic West End attendance has increased 11 per cent over pre-pandemic levels while Broadway attendance has fallen 17 per cent. As they grapple with divergent new normals, the duelling theatre capitals offer a study in contrast on recent racial justice efforts.Amid the Covid-19 pandemic and concurrent Black Lives Matter protests, Black Broadway blossomed. Plays by Black playwrights won the Pulitzer Prize four years in a row. Slave Play became the most Tony-nominated play ever. And Black playwrights wrote every new play — seven — that reopened Broadway. Chicken & Biscuits alone gave Broadway debuts to dozens of Black theatre professionals, including the director, 70 per cent of the cast, and Broadway’s first Black woman sound designer.But many Black Broadway professionals took umbrage at gaining prominence only in chaos and danger. “It was a joke,” says André De Shields, who recently reprised his Tony-winning performance of the Greek god Hermes in the West End’s Hadestown. “It was Broadway calling themselves allies without asking forgiveness, without risking reputation, without the revolution of reparation. They should’ve invested in what’s in our hearts, what’s on our minds, and all the secrets we’ve kept because they never looked us in our eyes. ”Ultimately, Slave Play won no Tonys, making it the most Tony-losing play ever. Those seven Black plays were rushed through previews and suffered chronic Covid-related cancellations, then sudden closures. Ain’t Too Proud, a Temptations musical, saw its gross plummet $797,835 in a single week. Thoughts of a Colored Man closed the day after announcing a new cast.“We need to broaden the idea of what a Black play can be,” says Reynaldo Piniella, one of those doomed thespians, “without sanitising the message, without spoon-feeding Black reality. Black joy. Black prosperity. Black belonging. Why can’t Shakespeare in the Park include Aimé Césaire’s A Tempest set in the Caribbean?” In 2021, New York’s off-Broadway Public Theater, which runs Shakespeare in the Park, set goals to provide living wages by 2023 and to make its staff, programming, and audiences 70 per cent non-white. The theatre’s communications director declined to comment on any progress.Speaking before his death last year, Ron Simons, a legendary producer of Black theatre, was blunt about Broadway: “It’s all the same people and they all look white. They want to do the right thing but they don’t know how to talk to or find people who are not white. They just don’t know. We need a Black owned and operated Broadway theatre where we are the final gatekeepers.”While Black theatre in New York has walked off a glass cliff, in London the glass ceiling has become a greenhouse. “We want to revel in joyfulness as an act of resistance,” says Carolyn Forsyth, executive director of Croydon-based Talawa, Britain’s oldest Black theatre company. “Culture is our right.”Lynette Linton, whose production of Alterations, a comedy of the 1970s Windrush generation, closed last month after a run at the National Theatre, agrees. “Black British theatre isn’t new. Its bravery isn’t new. Its creativity isn’t new. And its power isn’t new. It has always been here. What’s changed is that now we can put on a show like Alterations — written in 1978 — and celebrate work that was not celebrated as it should have been in its time.”Consider the Black queerness in Blackbird Hour, Black dignity in the Death of England trilogy, Black hustle in Wolves on Road, Black romance in Shifters, or Black history in The Legends of Them, The Lonely Londoners and Princess Essex.For decades Black British theatre was stuck in a cycle mentality — good years and bad years, feast and famine. “I don’t know if there’s one word for what’s changed in Black British theatre,” says Linton. “But I do know this: it’s the end of the cycle mentality.”It’s not just that a lot has changed since 1965, when Laurence Olivier performed Othello in blackface. A lot has changed since 2013, too, when the National Theatre opened its Black Plays Archive, with work dating back to 1909. Or 2018, when amid the backdrop of the Windrush scandal both the Black Ticket Project and British Black Theatre Awards debuted and Natasha Gordon’s intimate Nine Night, about a Black British family attempting a Jamaican tradition of mourning, made her the West End’s first Black British female playwright. Those 21st-century moments were all accelerators of Black excellence across British theatre.Broadway, by contrast, has stumbled. “Broadway is a representation of where America is,” says Zhailon Levingston, who in 2021 became Broadway’s youngest ever Black director, at 27. “But we’re going to see more original productions with an aim for America starting in London. What it does is test where our American values are.”Much of Black Broadway’s hope is pinned to Alicia Keys’ Hell’s Kitchen — which won a Grammy in February — a Black Gypsy starring Audra McDonald, Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’ new play Purpose, a new Afro-Latino musical about Buena Vista Social Club — which dominated last week’s Tony nominations with 10 nods — and The Jellicle Ball, a queer Black retelling of Cats aiming for a second run after closing in September. Meanwhile, Denzel Washington’s Othello has been panned by critics even as its nearly-$1,000 tickets created a record-breaking gross of $2.82mn a week. And a new Louis Armstrong musical — with a Tony-nominated performance by James Monroe Iglehart — closed after just 151 shows, including previews.Neither London nor New York consistently track race of theatre professionals citywide, but beyond tent poles such as Hamilton and The Lion King this West End season has Black leads in scores of productions, including Billy Porter in Cabaret, Vanessa Williams in The Devil Wears Prada, half the cast of I Wish You Well (a musical about Gwyneth Paltrow’s ski trial), General Turgidson in Dr Strangelove, a would-be Sidney Poitier in Retrograde, and revivals of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, The Grapes of Wrath, Guys & Dolls and A Streetcar Named Desire. Even the iceberg in Titanique is Black — and winning an Olivier for it.“London has now become the Boston of American theatre, the space where the narrative gets to be explored and experimented on to try something new,” says Jonathan McCrory, the artistic director of New York’s National Black Theatre, citing Boston’s history of incubation (of Hamilton, for one). “The pipeline is London to America.”Across London’s Black theatre renaissance, one name resonates: James Baldwin, one of many 20th-century Black American artists who fled the US for Paris. “I didn’t know what was going to happen to me in France, but I knew what was going to happen to me in New York,” he quipped. In the Baldwin model, is London now a fresh refuge for American or even global Blackness?Levingston sighs: “Baldwin is a reminder that you can leave America but America can never leave you.” Asked if he has considered life abroad, McCrory sighs too: “I’m trying to build my oasis here. I’m trying to get out of the burning building, to stop being a firefighter and start being a gardener.”Beyond the stage, there is the question of audiences. On Broadway, they are 71 per cent white, with theatregoers’ household income on average $276,375. London’s numbers are more elusive but the National Theatre’s audience is 89 per cent white.And there is no shortage of British racism. Francesca Amewudah-Rivers received death threats last year for playing a Black Juliet opposite Tom Holland’s Romeo. Kwame Kwei-Armah, former artistic director at the Young Vic, battled fundraising anxiety that his stages might become a “Black National Theatre”. And last year’s “Black Out” nights favouring all-Black audiences roiled critics all the way to Downing Street. But in London a progressive point of no return seems within reach. “I really don’t want to be having this same conversation in 10 years,” says Linton. “And I hope by then that the Oliviers have caught up to the Tonys in acknowledging Black talent.”Meanwhile McCrory details the challenge of being strategically undervalued: “The system isn’t broken. The system is working the ways it’s been wanting to work. We fight a system calling it broken. But it’s Broadway pushing up against its nature as a good ol’ boys club. The question is: do we have the patience for that journey?”

رائح الآن

rewrite this title in Arabic How London, not Broadway, became a crucible of Black theatre

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2026 جلوب تايم لاين. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.