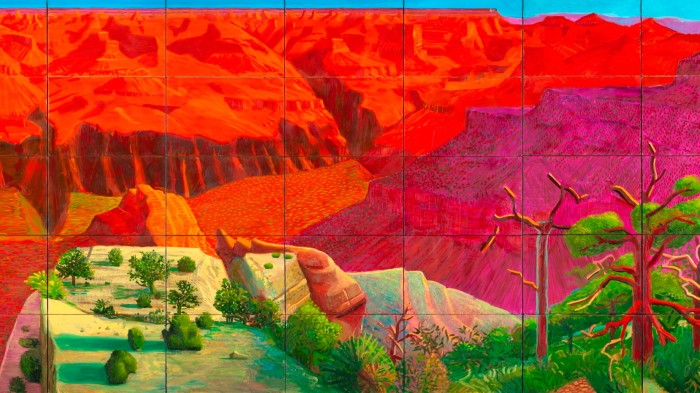

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic It is a country for old men, the latest, brightest, riotously enjoyable, largest ever incarnation of Hockneyland, just opened at Paris’s Fondation Louis Vuitton. Its president Bernard Arnault, 76, invited Hockney, 87, to fill the cloudscape museum designed by his friend Frank Gehry, 96, and curated by another friend, Norman Rosenthal, 80. The theme? Hockney has scrawled in pink across the building’s facade “Do remember, they can’t cancel the spring”. But the real subject is the cycle of life, nature’s and Hockney’s: this elegiac, flamboyant exhibition of Hockney-picked greatest hits is likely the last in his lifetime, his own distillation of one of the most beloved oeuvres in postwar art.David Hockney 25 features abundant renderings of the seasons in Yorkshire and Normandy made this century — best are the surrealist-pointillist magnified natural forms as explosive spurts of paint “The Big Hawthorn” and “May Blossom on the Roman Road”, and the beaming, simplified yellow/magenta “Winter Timber” — but it is also a retrospective, unmissable as a roll call of 1960-90 icons.American freedom and Hollywood hues surge in “A Bigger Splash” and “Pacific Coast Highway and Santa Monica”. Adolescence awakens to its own desirability in “The Room, Tarzana”, afternoon light pouring on semi-nude Peter Schlesinger. Provençal tristesse suffuses “Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures)”, Schlesinger surveying a swimmer in Hockney’s translucent blue — at $90mn, the most expensive painting by a living artist at auction. The newest painting is “Play Within a Play Within a Play and Me with a Cigarette” (2024-25), Hockney’s head framed by a bare twisting tree as he sits, in tweed suit and round glasses, painting himself among sketchily notated daffodils and irises, spring’s harbingers. This self-portrait looks back to “Play Within a Play” (1963), depicting Hockney’s jittery dealer John Kasmin throwing up his hands, trapped behind a sheet of Plexiglas nailed to a painting of totem figures and tapestries. It in turn connects to the marvellous early stage-set pictures which begin the show.Greeting you at the start are the uncanny pair “The First Marriage (A Marriage of Styles I)” (1962), pinstriped husband accompanying wooden sculpture, and “The Second Marriage” (1963), exceptionally borrowed from Melbourne: a shaped canvas boxing in a funereal bride, Egyptian mummy face, black stilettos, on a sofa with her realistically depicted suited husband, framed by a curtain. They herald the witty push-pull between artifice and crystalline realism that defines mature Hockney: effortlessly accessible, yet seriously engaging as a sophisticated creator of pictorial worlds.No expense or persuasion has been spared to bring to Paris key, far-flung pictures absent from Tate’s 2017 retrospective. “A Bigger Grand Canyon” (1998), the 60-part cubist-derived multiple viewpoints immersing us in seven metres of glowing gold, crimson and vermilion, visits from Canberra: a gripping tension between painterliness and design, voluptuous colour improbably meeting modernism’s geometric grid.Fresh to European audiences will be “Adhesiveness” from Fort Worth, two Dubuffet-inspired graffiti blocky figures in the 69 position; this and Oslo’s “Two Men in a Shower” are the most explicit examples of Hockney’s daringly original 1960s odes to gay love, made when homosexuality was illegal in Britain.Hockney himself got on the phone to secure Lisbon’s seldom loaned, pivotal “Renaissance Head” (1963): a deliberately crude response to a profile portrait by Pollaiuolo, painted with tremendous gestural freedom, yet drawn with linear precision. Its cool stylisation and ambiguity anticipate Hockney’s laconic double portraits, both lesser-known surprises — “Henry and Raymond”, curator Henry Geldzahler and writer Raymond Foye in energetic conversation against a loose abstract ground — and celebrities.“Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy”, remote behind a table laid with phallic banana and corn cob, and textile designer Celia Birtwell and Ossie Clark languidly unhappy in the picture-perfect 1970s interior “Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy”, are magnificent portraits of psychological distance, landmarks chronicling societal change, postwar affluence, style, individuality.Ascending the Vuitton, you re-encounter Birtwell, distinctive blonde curls, big blue eyes, soft features, Hockney’s enduring muse and companion in fashion-as-pattern. “Celia in Stripes” and “Celia in Black Dress” hang in a gallery with the jaunty ink-jet portrait “A Bigger Matelot, Keven Druez 1”, depicting the nephew of Hockney’s partner Jean-Pierre Goncalves de Lima and referencing Matisse’s “Young Sailor”. Such later works lack Hockney’s 1960s-70s edgy brilliance, but their warmth and facility still please. His Birtwell embodies swinging London and graceful ageing. That is the bottom line: “I make images. I’ve made memorable images, quite a few. Most people haven’t made any,” Hockney says.The Vuitton’s flow of monumental galleries plus compact spaces give Hockney the master of spectacle full scope without overwhelming smaller works. Opera resounds from the top floor installation of film renderings of his stage sets: the dynamically cross-hatched “Rake’s Progress”, the blue china “Le Rossignol”, “Tristan und Isolde”’s vast swaying ship. It is intoxicating and engrossing, but as potent are the intimate, unknown charcoal/crayon portraits from 2018-19. Hockney’s touch is light and sure as ever, sympathetic equally to teenage emerging identity — serious “Rufus Hale” in opulent green armchair — and old age’s stubborn resignation and interiority: Picasso’s biographer John Richardson, 94, a massive slumping presence.Youth and age, memory and desire, time lost and regained, are the threads uniting a very diverse show; in the superb catalogue co-curator Suzanne Pagé notes that if Hockney expresses the childlike wonder of The Little Prince, he is also a devotee of Proust.In “Flight into Italy — Swiss Landscape” (1962) Hockney lurches in the back of a car hurtling along a map-like Alpine route. That open road spirals past waterfalls in luscious Fauvish pigment, straight from the tube, in “Nichols Canyon” (1980), and a juicy purple streak bounces down patchwork fields in “Garrowby Hill” (1998). California’s wide vistas inform Yorkshire’s then Normandy’s, depicted from the home Hockney acquired there in 2019. When ill health forced him to relocate to London in 2023, Normandy became another remembered Eden, though he opens this series comically, with an animated iPad drawing of incessant rain.Lackadaisical or ironic titles — “Lots of Blossoms on Trees”, “Some Smaller Splashes” — imply Hockney knows the Norman paintings and iPad sketches are faux-naïf, easy codas to his life-long lucidly observed, ebulliently heightened realism. But still he remains in dialogue with French painting’s supreme hedonists. “Giverny by DH” opens out Monet’s pond into a diagram of curling and massed reflections of trees and clouds, lilies as yellow blots, recalling also Matisse’s response to Giverny, the abstracting flattened “Garden at Issy”.And among Hockney’s iPad animations are 12 panels depicting Normandy through the seasons, dawn to twilight, which unite finally into one sunburst image captioned and titled with a quotation from La Rochefoucauld, “Remember You Cannot Look at the Sun or Death for Very Long”. To August 31, fondationlouisvuitton.fr

رائح الآن

rewrite this title in Arabic David Hockney hand-picks his greatest hits at Paris’s Fondation Vuitton

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2026 جلوب تايم لاين. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.