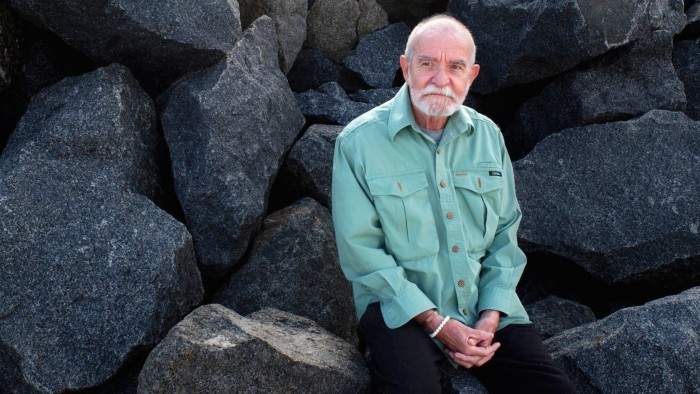

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic Unlock the Editor’s Digest for freeRoula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.On July 2 1973, Athol Fugard, Yvonne Bryceland, John Kani and Winston Ntshona gazed out of a window in Cape Town’s Space Theatre that gave on to Robben Island, where Nelson Mandela had already been jailed for 10 years. Kani and Ntshona were about to deliver the first performance of The Island, which they had written with Fugard. “It was just one of those moments when you feel truly humbled,” he recalled three decades later. “We were going to try to bear witness, honest witness, to what that island meant for fellow South Africans.”Telling the story of his beloved country was a burden and a blessing for Fugard, who has died at the age of 92. Judged the “greatest active playwright in the English-speaking world” by Time in 1985 — praise he later dismissed as “nonsense” — Fugard picked repeatedly at the scabs of apartheid, exposing the injustice of the state-sanctioned system of racism. After it ended he carried on, not to stop old wounds healing but to help remember and move on. In more than 30 works of drama, and for a long time in defiance of Pretoria, he drew on true stories of which his homeland could not be proud, insisting that things should be otherwise. “I think it is under the pressure of desperation that extraordinary things can happen in a human life,” Fugard reflected in 2014. “And if ever there was a country oversupplied with desperation, it was South Africa in that time.”Born on June 11 1932 in Middelburg, a town in the semi-desert Karoo region, Fugard was the child of Harold, a jazz pianist from Manchester, and Marrie, an Afrikaner café manager. From his father, Fugard said he inherited a love of English, and from his mother “a sense for injustice”. They moved to Port Elizabeth when he was a toddler, and as the self-described “bastard” grew up he detected — and resisted — “what the system was trying to do to me . . . the way it was trying to pull me”. After studying mechanics at college, he enrolled in philosophy at the University of Cape Town but dropped out to travel. A job in Egypt on a merchant ship, where he was the lone white man, gave rise to a bad novel. But he returned home resolved to write. Early plays met with little success. His break came in 1961 with Blood Knot, in which he and Zakes Mokae played two half-brothers separated by their colour. The play travelled to London and later starred James Earl Jones off Broadway. After it was broadcast on the BBC in 1967, the National party government cancelled Fugard’s passport.Rather than leave South Africa and never return, he stayed. With Ntshona and Kani, Fugard went on to produce Sizwe Banzi is Dead (1972) and The Island, in which two Robben Island inmates put on a version of Sophocles’ Antigone. “All paths lead not to Rome, but to Athens,” Fugard mused, pumping his fist in the air when Kani and Ntshona won Tony awards.Sir Richard Eyre, artistic director of Nottingham Playhouse in the mid-1970s and later of the Royal National Theatre, told the Financial Times that Fugard had “voracious energy” and an “almost predatory curiosity”; the pair met in 1976 as Dimetos was staged in the Midlands city, after an international campaign forced Pretoria to return Fugard’s passport. But that “he had to know what all the pubs in the city were like” was a hint at the alcoholism Fugard acknowledged as “a thread running down the [family] line”. An “instinct for survival” ended his drinking on a winter’s day in New York City in 1982.In later life Fugard, who is survived by his second wife, Paula Fourie, and three children from both his marriages, spent stretches teaching in California and adopted “a more personal idiom”. The Shadow of the Hummingbird (2014) was inspired by his relationship with his grandson. In 2011 he became the first non-American to win a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Tonys.Although he never met Mandela — who on Robben Island played Creon in Antigone — Fugard admired him. But he had little time for Thabo Mbeki, decrying his “ludicrous” approach to HIV/Aids. The passage to democracy risked rendering him South Africa’s “first redundant writer”, he joked. Yet he reckoned his homeland needed young authors “more than ever”. Looking back on his writing life in 2014, Fugard echoed Mandela, who spoke of how love “comes more naturally to the human heart than its opposite”. Ultimately, the playwright had learnt one thing about himself. “It came quite early in my life,” he reflected. “I realised one day what is necessary is that you leave the destructive negative emotions . . . outside the door and close the door. The only emotion that I sit with when I write is love.”

rewrite this title in Arabic Athol Fugard, playwright, 1932-2025

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2025 جلوب تايم لاين. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.