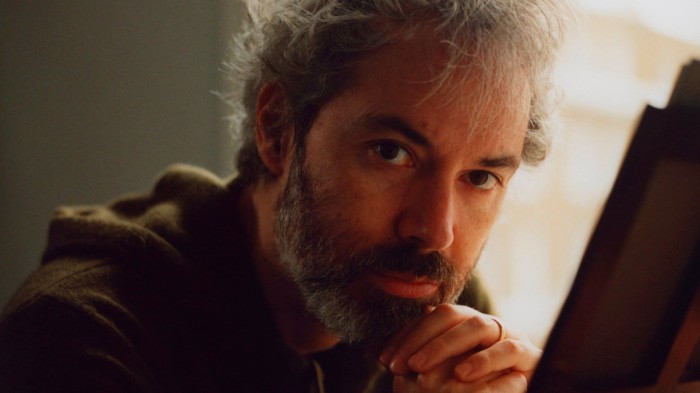

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic Unlock the Editor’s Digest for freeRoula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.By now we’re all familiar with the idea of music as therapy. For James Rhodes, however, music can be equivalent — at times even preferable — to medication in the management of mental health. “Obviously, I am in favour of medication when it is necessary to save lives,” says the 49-year-old British-Spanish classical pianist, when I meet him at Peregrine’s, an upmarket piano shop in Clerkenwell, central London. “I was on medication and it genuinely saved my life. What I’m not in favour of is medication as a kind of easy option instead of doing other things that will also have the same effect. And there’s no question that music [can].”Manía, Rhodes’s new album, is driven by that philosophy. Traversing swaths of classical territory, from JS Bach to 20th-century Argentine composer Alberto Ginastera, it is an attempt to profile the therapeutic properties of music from all angles. “I’ve always loved this idea of prescribing pieces,” says Rhodes. As someone who has long struggled with his own mental health, he says he has selected works that “accompany me and my insomnia, my anxiety, my desperation and my fears in the middle of the night”.He draws my attention to the works’ individually uplifting qualities: the exhilarating energy of Rachmaninov’s Moment Musical No. 6 in C major, for example, or the calm contemplation of the same composer’s Étude-Tableau, Op. 33 No. 3 in C minor, which Rhodes likens to “that super slow kind of yoga where you hold every pose”. But, he insists, there’s more than this to their psychological impact. “Music is purity; it’s just pure good; like children and puppies and that stage in life when everything is OK, before the world comes and beats the shit out of you.” Music is purity; it’s just pure good; like children and puppies and that stage in life when everything is OK, before the world comes and beats the shit out of youEver since Rhodes burst on to the musical scene about 16 years ago, he has consistently flouted convention. He frequently appears onstage in jeans and T-shirt, speaking directly to the audience and investing pillars of the classical repertoire with a sense of jeopardy. Offstage, he has been known to launch into expletive-peppered tirades.Yet the man with soft brown eyes sitting in front of me comes across as far more gentle and quietly reflective than I had anticipated. “My big fear,” he tells me, “is that I’m broken at some level. It drives me absolutely up the wall with frustration . . . that I’m going to be 50 this year, and it is still there.” He doesn’t go into detail but I have read his harrowing 2015 memoir Instrumental and know what he is referring to: a legacy of trauma stemming from having been raped repeatedly, at the age of six, by a PE teacher at his North London prep school.In the book, Rhodes outlines the physical and psychological consequences of the ordeal: the serious spinal injury it left him with, requiring reparative surgery; as well as depression, drug and alcohol abuse, eating disorders, nervous breakdowns, suicide attempts and time in a psychiatric hospital. What emerges is a story of anger and turmoil, but also a celebration of Rhodes’s musical passion and his determination, in spite of everything he went through, to turn that passion into a career.He was seven when he found a recording of Bach-Busoni’s Chaccone on an old cassette tape and started teaching himself the piano. At 18 — only four years after starting formal piano lessons — he was awarded a scholarship to study at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, but he never accepted it. Instead, he took a decade-long break from the piano, before returning to it with a vengeance at the age of 28. “I found a teacher in Italy. He was aggressive and violent, but a genius. He really got me into shape.” Rhodes gave his first public recital at London’s Steinway Hall in 2008, aged 33.Since then, he has used his profile to promote causes that matter most to him and is proud of having successfully pushed for a new law on child protection in Spain, where he has lived since 2017. But he still laments what he views as the current “epidemic” of poor mental health. “I would not hesitate to say that [our] mental health is worse [than in the past] . . . I remember a time when, if you left the house in the morning on a weekend, you couldn’t be contacted until you got back . . . Nowadays, the world is operating at a pace and a rhythm that is just not sustainable.”Does he think the demands of a music career — the public scrutiny; the perfectionism — might intensify psychological struggles? The answer is a vehement “no”. “I don’t like this weird kind of Hollywood idea of the tortured artist . . . Show me one person [in any field] who doesn’t have those struggles . . . I had the same fear and stress going to a shift at Burger King when I was 19 as I had playing at the Liceu in Barcelona.”Such statements appear to fly in the face of recent research into mental health and the music industry. One of the largest studies to date, commissioned by Help Musicians in 2016, found that musicians may be up to three times more likely to experience depression than the general public, with more than seven out of 10 reporting that they had experienced anxiety and panic attacks. But when I mention this to Rhodes, his response is polite scepticism: “I imagine artists may self-report more easily, and that could well skew any results . . . I simply refuse to believe that musicians are more vulnerable to depression. It seems absurd to me and empirically dubious.”If anything, he says, going on stage nowadays gives him respite from psychological distress “because I [get to] remove myself from the equation completely. All I’m trying to do is say: ‘Just listen to this piece.’” But is there a risk of overstating the healing properties of music? “What music does is turn up the volume on your emotions — and that can be a difficult thing if you’re in a dark place,” he admits, before insisting that he is not advocating for the idea of music as a panacea. “If you’re suffering from schizophrenia, for example, then listening to Bach is not going to [solve the problem].”So what exactly is he advocating for? “Music is one of the few ways of just disappearing in a healthy way from reality. It’s an escape . . . and it bypasses everything; it goes underneath words straight to the emotions.” He concludes: “So if we’re talking about finding a small number of things that are greater than the sum of their parts, that add joy to your life, then music is absolutely one of them.”‘Manía’ is released on March 14Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning

rewrite this title in Arabic Pianist James Rhodes on prescribing music for mental health

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2025 جلوب تايم لاين. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.