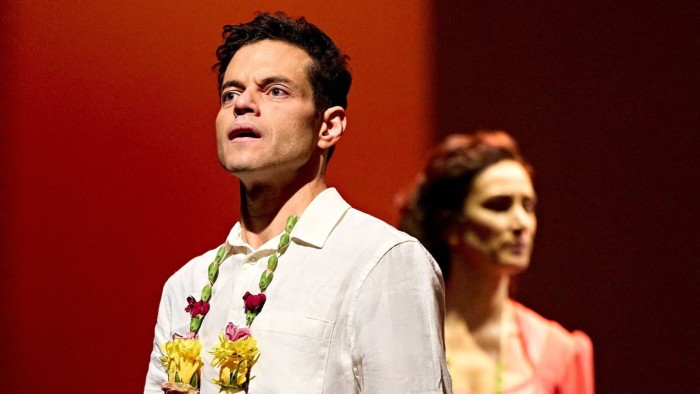

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic Unlock the Editor’s Digest for freeRoula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.Maybe it’s coincidence. Or maybe there’s something in the air that has drawn theatre directors recently to an ancient tragedy about hubris in powerful leaders. Either way, here we are with the second major London production of Sophocles’ Oedipus within months — this time it’s Rami Malek and Indira Varma spiralling into the vortex. Again it’s a collision of ancient and modern, again it raises huge questions about knowledge, truth and power, how much we want to know and why. But where Robert Icke’s recent staging at Wyndham’s Theatre measured up to the implacable horror of Oedipus’s fate by sucking it into a familiar political world of spin-doctors and screens, Matthew Warchus’s production, co-directed with choreographer Hofesh Shechter and infused with a strong sense of ritual, goes the other way. Humans here feel tiny — pinned against the vastness of time and fate. There’s an elemental grandeur to the staging, but, while it’s spectacular, what it loses somewhere is the human pathos of the tragedy.We’re in a bone-dry, near-future world where water is scarce, the people are desperate and reasoned response is giving way to religious hardliners, led by Oedipus’s power-hungry brother-in-law Creon (Nicholas Khan). Malek’s King Oedipus, a slight, awkward figure suddenly feeling his outsider status, offers to consult the oracle to quell disorder. He’s delighted when it comes up with a solution — find the former king’s killer and the rains will come. Soon he’s scrabbling through old box-files of evidence and there’s no saving him from the truths he will uncover. The production looks sensational, the cavernous depths of the Old Vic stage sculpted by Rae Smith’s sliding screens and Tom Visser’s stark lighting, which silhouettes the royal family against throbbing, merciless sunbursts or in icy, dark interiors. Shechter’s brilliant chorus of dancers swirl across the space like dust clouds, writhe across the back of the stage in a seething mass, or suddenly surge to the front and loom over the audience: a desperate, parched crew who evoke distressed peoples across the ages. Our own responses to climate change, and the menace of populist leaders and shifty advisers, hang over the whole show. And yet there’s something here that doesn’t click. The dance segments mean the story is splintered, delivered in clipped, disjointed sections, and we lose the urgency and skin-prickling dread that should accompany Oedipus’s journey. Ella Hickson’s script crunches the poetic together with the vernacular and makes Jocasta — a fine, impassioned performance from Varma — a voice of reason, urging her stubborn husband to lead his people to safety. Cecilia Noble’s formidable seer, Tiresias, complains of being dragged from her cup of tea to prophesy. Even so, the characters seem weirdly remote and disconnected: Malek’s angular, expressionless Oedipus feels like a man uneasy in his own skin, which makes sense, but he finds no change of tone as the devastating truths of his existence hit the light. It’s hard to feel anything for him, or even to believe in a real connection between the couple, and without that we lose much of the tragedy. Perhaps that detachment is intentional. The dancers end up sitting on the ground, gazing into the distance as if waiting for the next tough-talking leader to turn up and strut about grandly. But for all its stark physicality, this telling of the tale doesn’t reach into your core and rattle you with its painful, nagging questions about fate and human agency. ★★★☆☆To March 29, oldvictheatre.com

رائح الآن

rewrite this title in Arabic Oedipus at the Old Vic theatre review — a stark, physical staging of Sophocles’ tragedy

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2026 جلوب تايم لاين. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.