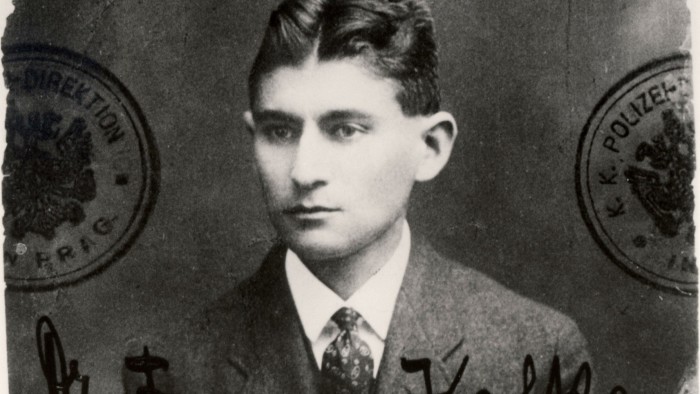

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic Franz Kafka’s handsome face, with its patrician cheekbones, tremendous dark eyes and vaguely ironic expression, has become a visual representation of angst, more understated but no less powerful than Munch’s “Scream”. We have come to think of the man behind the “-esque” as a soul in perpetual conflict with the absurdities of modern life, its spiritual dislocations and irreconcilable contradictions.But a sparkling exhibition at the Morgan Library in New York, marking the centenary of his death in 1924, proves that there was more to Kafka than despair. Far from being an isolate who nursed his anguish in solitude, he was a social being with a job, a family and an ample circle of co-workers, friends and lovers.The Morgan lays out both the truth and the ways in which posterity tweaked it to make him conform to the lonely antiheroes of his books. As a young man, Kafka posed in a suit and a bowler hat with a companion, the grinning barmaid Juliane Szokoll, and a German shepherd. Later, a French publisher excised the woman from the photo and left in the blurred dog, so that readers would focus on the author’s melancholy eyes. (Given the choice, Kafka might have cropped himself out, too: “All knowledge, the totality of all questions and all answers, is contained in the dog,” he wrote.)It’s a good thing that he was no recluse, since we owe the survival of his work to one of his closest friends, the writer Max Brod, who providentially ignored the instructions Kafka left in his Prague desk when he died: “Everything I leave behind me . . . in the way of diaries, manuscripts, letters (my own and others’), sketches and so on, to be burned unread.”It opens with a scale model of the apartment where he grew up and remained — unhappily — well into adulthoodBrod never took Kafka’s demand seriously. Instead, he arranged the posthumous publication of “The Trial” (1925), “The Castle” (1926) and “Amerika” (1927). In 1939, minutes before the Nazis shut down the Czech border, Brod fled for Palestine with a suitcase crammed full of his old friend’s papers. Thanks to Brod’s foresight and loyalty, a long-dead, obscure insurance officer, who had published only a handful of stories before dying at 40, became a colossus of 20th-century literature.Here, we get a jigsaw-like portrait of an artist navigating the complexities of full-time employment, family life, social life, love life and the tuberculosis that would kill him. It opens with a scale model of the apartment where he grew up and remained — unhappily — well into adulthood. It was a tiny flat, where Franz, his parents and three sisters were jammed together in almost unbearable proximity. He did have the privilege of his own bedroom, but it didn’t afford much privacy since the others had to walk through it to get to the rest of the living space. The constant tumult drove him crazy.“How to concentrate when your family is making lots of noise?” he wrote in a 1912 essay that was published in a Prague literary journal. The Morgan has the original version of that timeless complaint, salvaged from the diary he had hoped to destroy.Kafka’s private outpourings include a letter he wrote to his father Hermann in 1919, a 100-page handwritten bill of particulars. (He typed it up and entrusted delivery to his mother, who diplomatically pocketed it.) The single sheet on display is a doozy, detailing Hermann’s unremitting bullying and emotional abuse. In one traumatic incident, the father shoved the young boy out on to the apartment’s little balcony and locked the door.Franz loved his youngest sister Ottilie (nicknamed Ottla) best, and the museum has gathered dozens of postcards, letters and photos of this favourite sibling, revealing a snarky sense of fun and intense affection. He encouraged her to pursue an advanced agriculture degree, researched schools and even offered to pay for her education.In 1917, he wrote to her about his illness, and his detailed but impassive description of the symptoms is chilling. “About three weeks ago, I had a haemorrhage from the lungs during the night . . . I thought it would never stop . . . I got up, walked around the room, went over to the window, looked out, went back — still blood.”He visited her to convalesce on the farm where she worked during the war and wrote to her from a succession of sanatoria. He adorned one postcard with comical stick-figure self-portraits (“snapshots from my life,” he called them): sleeping, a lump in the bed; waking, arms and legs akimbo, stretching towards an invisible bird’s eye; as a tiny speck, seen from behind, at a prodigally laid table.Kafka was a vegetarian, which was rare enough that he regularly needed to remind his sister. In one letter, he describes being served roast veal in the Bohemian town of Kratzau. “As you know I cannot properly chew [meat],” he reported. So he diverted it, “partly to feed a cat, partly just to mess up the floor.”The character who comes through in this assortment of documents and memorabilia is not the muttering introvert of popular imagination, but an eccentric, fearful, neurotic, insecure, witty and gregarious man. The exhibition lingers on his affairs with women, among them Felice Bauer, whom he agonised over for five years and through two aborted engagements.His first impression of her was not auspicious. “Bony, empty face that wore its emptiness openly . . . Almost broken nose. Blonde, somewhat straight, unattractive hair, strong chin.”He fell in love anyway, wrote to her obsessively, and was both attracted and repulsed by the prospect of marrying. When they agreed to wed, Kafka confided to his diary that he felt “tied hand and foot like a criminal”. They split up a few weeks later — and got back together several years after that.The show offers up scattered evidence of happiness, like the postcard he sent to Ottla from the resort town of Marienbad, where he and Bauer were on vacation. The following year, the couple got re-engaged and posed together for a formal portrait, their expressions solemn, as the conventions of studio photography demanded. Six decades later, Andy Warhol used that picture as the source for his silkscreen print, cropping out Bauer to give us a portrait of the pensive loner.Kafka remained tormented about their future together, and his illness put the kibosh on the romance. They cancelled wedding plans again, this time for good. Still, his affairs with women continued. He was briefly engaged to Julie Wohryzek, then cheated on her with his married Czech translator, Milena Polak.Finally, in 1923 he met the much younger Dora Diamant, who stuck by him, nursed him through his final days, and held him as he died. He told her, too, to burn his letters and notebooks; she made a show of obeying by sacrificing a few, later sent others to Brod, and squirrelled away the rest. Those literary keepsakes are missing, though, because in 1933 the Gestapo confiscated them from Diamant’s home. They may still exist, but they have never been found. How poetically just that, long after Kafka’s death, a chunk of his life was swallowed up by a murderous bureaucracy.To April 13, themorgan.org

رائح الآن

rewrite this title in Arabic Franz steps out of the shadow of his ‘Kafkaesque’ world

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2026 جلوب تايم لاين. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.