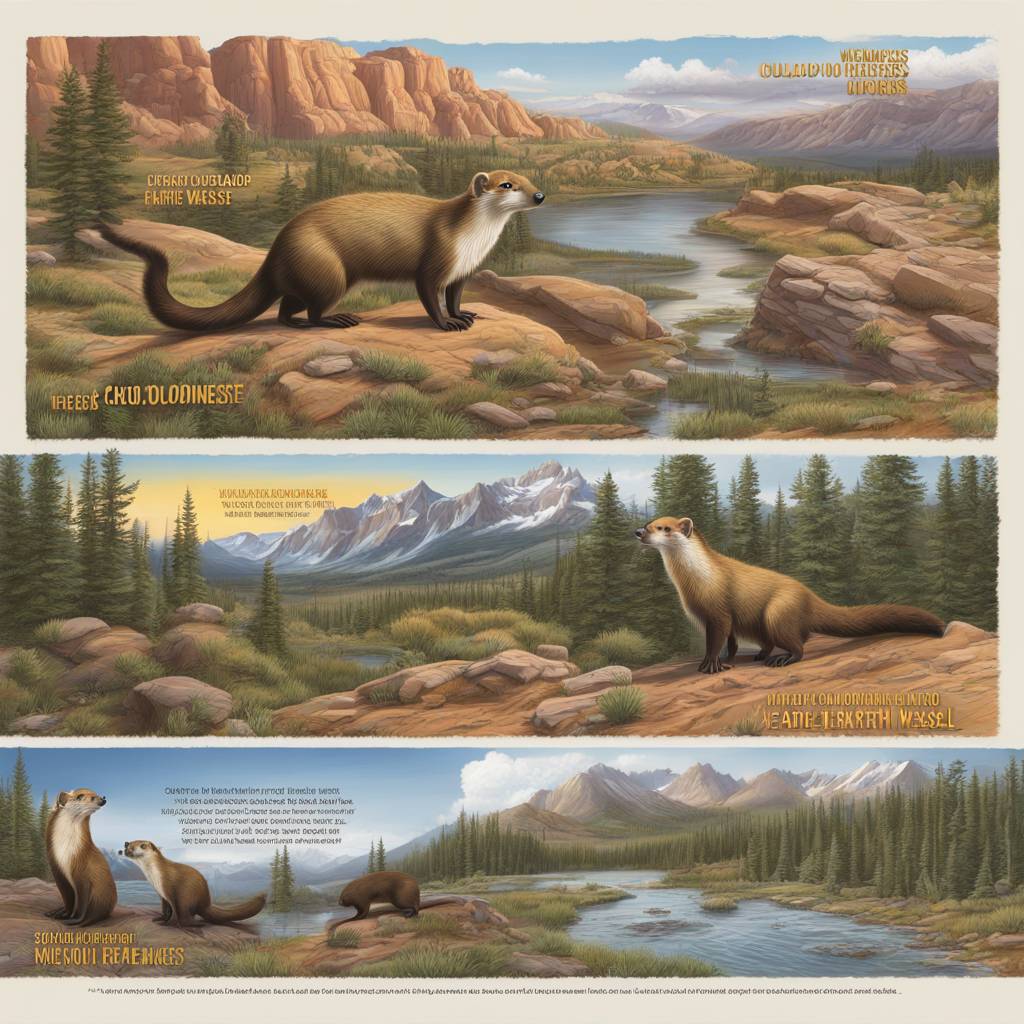

Colorado’s Senate Agricultural and Natural Resources Committee has voted in favor of a bipartisan bill that would reintroduce wolverines into the state, bringing a wolverine “rewilding” effort closer to becoming a reality. The proposed legislation, led by Senators Dylan Roberts and Perry Will, highlights Colorado’s ideal habitat for wolverines, stating that the state has some of the best remaining unoccupied wolverine habitat in the lower forty-eight states. Advocates believe that reintroducing wolverines would restore a natural part of Colorado’s landscape and improve the health of the mountain ecosystem.

Unlike the controversial reintroduction of wolves last year, wolverines are seen as less contentious due to their minimal impact on livestock. With the current bill designating wolverines as a “nonessential experimental species,” it aims to make coexistence with wolverines easier for industries such as agriculture, ranching, and tourism in Colorado. This approach is expected to mitigate some of the more stringent land use requirements associated with endangered species. Advocates of the reintroduction believe that the effort is backed by science, supported by stakeholders, and has bipartisan backing.

In Sweden, a successful conservation program has shown how to protect wolverine populations effectively. The conservation performance payments (CPP) system incentivizes reindeer herders to protect wolverines in their districts by offering financial rewards for documented wolverine reproduction. This approach has led to a significant increase in wolverine populations in previously unoccupied areas. In contrast, Norway and Finland, neighboring countries to Sweden, have been less successful in sustaining their wolverine populations without similar performance-based incentives.

Despite the possibility of reintroduction, wolverines face additional threats, such as the impact of climate change on their denning sites. Researchers are concerned that decreasing snowpack could restrict wolverine denning opportunities, forcing them to higher elevations and further fragmenting their range. Human development, roads, and agriculture also hinder wolverines’ ability to disperse, putting pressure on their survival. As solitary predators, wolverines rely on scavenging opportunities from other predators, such as lynx or wolves, highlighting the interconnected nature of predator relationships.

Colorado’s proposed rewilding effort for wolverines may indirectly benefit from the state’s wolf reintroduction plan, as predators like wolves and arctic wolverines have been observed feeding on the same carcasses. This highlights the complex and interdependent relationships within ecosystems, demonstrating that predators can help each other indirectly when food sources are scarce. As efforts to reintroduce wolverines progress, it is important to consider the broader ecological balance and the potential ripple effects of reintroducing one predator species on another.