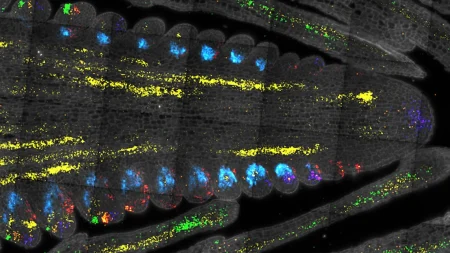

Bioluminescence, the ability of living things to produce light via chemical reactions, first evolved in animals at least 540 million years ago in a group of marine invertebrates called octocorals. This discovery pushes back the previous record for the oldest dated emergence of bioluminescence in animals by nearly 300 million years. The origins of this trait have remained mysterious, and scientists hope to eventually decode why the ability to produce light evolved in the first place. Bioluminescence has independently evolved at least 94 times in nature and is involved in a wide range of behaviors including camouflage, courtship, communication, and hunting.

To determine the timing of the origin of bioluminescence in animals, researchers turned to the octocorals, an evolutionarily ancient and frequently bioluminescent group of animals that includes soft corals, sea fans, and sea pens. Through an extremely detailed, well-supported evolutionary tree of octocorals created in 2022, the scientists were able to map out the evolutionary relationships of 185 species of octocorals. By situating fossils of known ages within the evolutionary tree and using statistical techniques for ancestral state reconstruction, the researchers were able to determine that some 540 million years ago, the common ancestor of all octocorals was likely bioluminescent.

The high incidence of bioluminescence among octocorals suggests that the trait has played a role in the group’s evolutionary success, highlighting its importance for their fitness and survival. The fact that this ability has been retained for so long raises questions about what exactly octocorals are using bioluminescence for, sparking further research into the ecological circumstances and functions of this trait. Researchers are also working on a genetic test to determine if an octocoral species has functional copies of the genes underlying luciferase, an enzyme involved in bioluminescence, to help identify species that can produce their own light.

In addition to shedding light on the origins of bioluminescence, this study offers evolutionary context and insight that can inform the monitoring and management of octocorals, which are threatened by climate change and resource-extraction activities. The research also aligns with the Smithsonian’s Ocean Science Center’s mission to advance and share knowledge of the ocean with the world. While this study has provided valuable information about the evolution of bioluminescence, there is still much more to learn before scientists can fully understand why the ability to produce light first evolved, and future studies may uncover even more ancient origins of this trait.

The researchers involved in this study come from various institutions, including Florida International University, the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, Nagoya University, Harvey Mudd College, and the University of California, Santa Cruz. The research was supported by the Smithsonian, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, Japan Science and Technology Agency, and the U.S. National Science Foundation. By delving into the evolutionary history of bioluminescence in octocorals, this study has brought new understanding to the origins of this fascinating trait and its significance in the natural world.