A recent study led by USC researchers suggests that a diet high in fat and sugar could have long-lasting negative effects on memory function in adolescents. The study, published in the journal Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, focused on the impact of a junk food diet on acetylcholine levels in the brain, a neurotransmitter essential for memory and cognitive function. The researchers found that rats raised on a diet rich in unhealthy foods demonstrated memory impairments that persisted into adulthood, even when switched to a healthier diet later on. This raises concerns about the potential long-term consequences of poor dietary habits during critical periods of brain development.

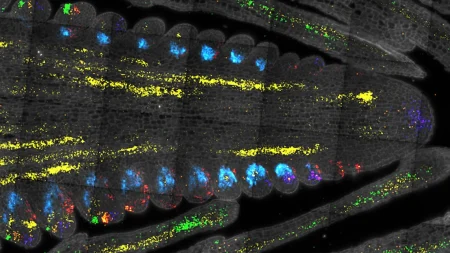

The study was motivated by previous research linking poor diet to Alzheimer’s disease, which is characterized by low levels of acetylcholine in the brain. Given that adolescence is a time of significant brain development, the researchers sought to understand how a diet high in fat and sugar might impact memory function in younger individuals. By analyzing acetylcholine levels in rats fed a junk food diet and comparing their performance on memory tests to a control group, the researchers were able to evaluate the relationship between diet and memory. The results showed that rats on the junk food diet had difficulty remembering objects and their locations, indicating a disruption in acetylcholine signaling critical for memory encoding.

Lead author Anna Hayes explained that acetylcholine signaling plays a crucial role in episodic memory, allowing individuals to remember past events. The findings suggest that the fatty, sugary diet interfered with this process, leading to memory impairments in the rats. Professor Scott Kanoski highlighted the vulnerability of the adolescent brain to such disruptions, emphasizing the importance of healthy nutrition during this critical period. While the memory impairments observed in the rats were significant, the researchers explored potential interventions to reverse these effects, including drugs that stimulate acetylcholine release.

In a subsequent phase of the study, the researchers investigated whether memory deficits in rats exposed to a junk food diet could be reversed with medication targeting acetylcholine release. By administering two drugs directly to the hippocampus, a brain region involved in memory function, the researchers were able to restore memory ability in the rats. This promising result suggests that medical interventions may help mitigate the negative effects of a poor diet on memory function. However, additional research is needed to better understand how memory problems resulting from unhealthy eating habits in adolescence can be effectively reversed or prevented.

The study involved a team of researchers from USC, including Logan Tierno Lauer, Alicia E. Kao, Molly E. Klug, Linda Tsan, Jessica J. Rea, Keshav S. Subramanian, Cindy Gu, Arun Ahuja, Kristen N. Donohue, and Léa Décarie-Spain, as well as collaborators from Keck School of Medicine of USC and University of North Carolina-Charlotte. The research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the National Institute on Aging, the National Science Foundation, and other funding sources. Overall, the study sheds light on the potential long-term consequences of poor dietary choices during adolescence and underscores the importance of healthy eating habits for brain health and cognitive function.