Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs Lagos, Nigeria – Fade Bey’s Decembers are usually packed with activities. In the company of friends and family, she hops from one bar, club and concert to the next, braving Lagos’s notoriously gridlocked traffic to sample cuisines at different restaurants around the city.

But this year, the holidays are bare-bones. Dressed in a T-shirt, the public relations consultant has ceded stylish clothes for more affordable hobbies, she said, as she moves between her couch and bed reading books and catching up on movies she missed during the year.

“I love eating out and buying gifts for the people that I love but that has changed this year because of the economy,” Bey, who is in her late 20s, told Al Jazeera. “I can’t buy for one person and leave other people standing, and I have also refused to receive gifts from people because I don’t want to feel indebted.”

Bey is not the only one abstaining from this year’s “detty December” – a monthlong end-of-year extravaganza popular in Nigeria and across West Africa filled with concerts, carnivals, beach activities, bar and restaurant visits, among others. The phenomenon is popular with the region’s locals as well as the vast diaspora community returning for the holidays and is a chance for people to socialise, reconnect and relax after a busy year.

But recently, the economic downturn in Africa’s most populous country is dampening the beloved tradition. This year, restaurants and bars are not as full as before due to eroding spending power brought on by President Bola Tinubu’s economic measures, experts say.

The country’s inflation, the highest in about three decades at 34.5 percent, has left millions reeling, straining the middle class and making life unbearable for the working class – who have been disproportionately affected – while the minimum wage is capped at a meagre 70,000 naira ($45.30) per month.

For many, basic amenities are now out of reach, forcing them to forgo meals, let alone recreational activities.

According to Lagos-based intelligence firm SBM, it costs 21,300 naira ($13.75) to cook a pot of staple jollof rice, up from 20,274 naira ($13.09) in June. Two in three families go hungry, according to the Nigerian Bureau of Statistics.

“This pricing makes it difficult for many Nigerians to even consider travelling, draining the energy and enthusiasm typically associated with the festive season,” said Adewunmi Emoruwa, the lead strategist at Gatefield, an Abuja-based public strategy group.

“There is despondency in the air, so palpable it feels like you could cut through it with a knife. It’s a stark reminder of how declining purchasing power and inflation are reshaping Nigeria’s social and cultural traditions.”

Detty December

Festivities are popular in cities and towns across Nigeria, with small street carnivals, communal festivals, food and fireworks taking centre stage in many places in December.

But Lagos, the country’s economic and entertainment capital, features the most dynamic itinerary, including concerts, parties, and a host of activities spanning the whole month until the first weeks of the new year.

Restaurants are usually booked out, the beaches filled and concert venues packed. At its peak, the clubs remain in action for 24 hours a day.

Historically, December, which is packed with important holidays, has always been a time of fun and rest. Since 2016, entertainment avenues have expanded even more.

Music played a big role in this, explained OluwaMayowa Idowu, a Lagos-based cultural connoisseur who runs a company focused on African culture and entertainment. As the Afrobeats genre grew and began to gain wider global appeal, the detty December culture expanded – “detty” being a light-hearted derivative of the word “dirty”.

Artists would also target December for the release of their major projects, with concerts, festivals and shows specifically lined up for the holiday period as promoters quickly caught on.

“In terms of when we started to use detty December as an appellation, I think it was in 2016. It came from Mr Eazi when he used it as a hashtag for his concert in Lagos in 2016 and the name just caught on,” Idowu said, talking about the Nigerian singer, adding that the phenomenon soon spread across the region, also helped by the fact that Mr Eazi had a large following in Ghana.

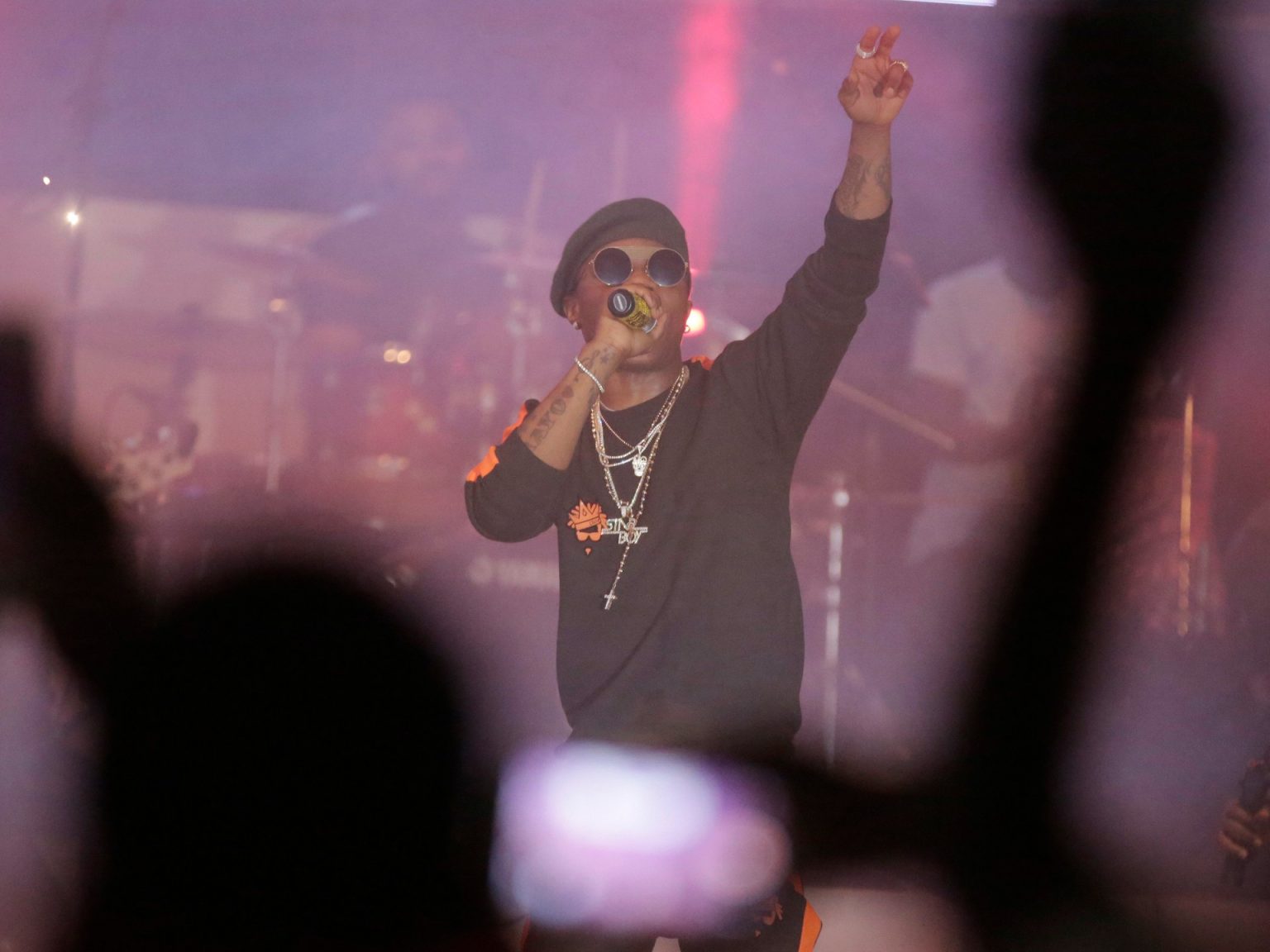

In the years that followed, top artists, like Burna Boy and Wizkid, would hold concerts in December, drawing crowds to the festivities. But many see a change this year, with many big acts not joining in on the action.

‘I Just Got Backs’

One group that has come to be synonymous with detty December is IJGBs – or Nigerians living in the diaspora who return home for visits, and have earned the moniker “I Just Got Backs”.

Every year, IJGBs make a trip back to Nigeria to partake in the festivities and feel the pulse of the season.

This December, 33-year-old Valerie Eguavoen is among the members of the diaspora back in Lagos to satiate an overwhelming desire to be home and spend time with family and friends. Early in the year, she started making plans for her trip, also inviting a few of her friends along.

“They are African Americans and it was their first time on the continent – as you can imagine it was a significant trip for them,” she said, also explaining the work planning their travel, and applying for visas for non-Nigerians.

“It was quite an ordeal and very expensive,” she said, adding that though there is fun to be had, this is also a stressful time to be in Lagos.

Lagos is already bustling. But it comes into full force in December – with roads, especially on the affluent island, regularly blocked and traffic at a standstill for hours. Those who remain mobile are usually government officials and celebrities wealthy enough to afford a convoy that offers protection and clears a path on busy roads using military force.

For visitors like Eguavoen, often using taxis and ride-shares like Bolt and Uber, a 30-minute drive can last two hours, and the prices rise with it – often beyond the means of the average person.

Due to the naira’s weakness compared with the US dollar, British pound and euro, the IJGBs have higher spending power when visiting home. Their foreign currency also helps the country’s economy going into the new year. Capitalising on this, many businesses have been known to inflate the price of goods and services in December.

But this year, inflation has left even IJGBs shocked, despite their dollar advantage. Prices of food and drinks are soaring. Eguavoen was also surprised.

“There is no doubt that there is a ‘December tax’ on top of the existing inflation in the country. I have been taken aback by the cost of meals and clothing at certain places. But, overall, it is not surprising. We’ve all observed the downturn of the Nigerian economy in the last few years and it is only getting worse under the administration,” she said.

Still, the situation has not deterred Eguavoen and her friends from their holiday plans.

The group has been to some “popular overpriced restaurants” and party spots in the city. But “we did not come to Lagos just to party”, she said, adding that they also visited historical sites, markets and local staples.

“Overall, I believe they experienced a very non-traditional detty December,” she told Al Jazeera about her friends. But it is not something she is disappointed about.

As in Nigeria, so in Ghana

Diaspora dollars no longer offer a huge boost for the Nigerian economy, but merely inject some liquidity which gives a tiny lifeline, experts say.

“[This is] due to more money chasing a reduced supply,” Gatefield’s Emoruwa told Al Jazeera. In fact, “their money could easily create the unintended consequence of further increasing inflation during the holidays, compounding the woes of economically distressed locals who might struggle to compete for the same set of goods and services”.

“This was [also] the case in Ghana,” he said.

This year has been a particularly dramatic year for IJGBs, who have been met with hostile treatment from home-based Nigerians who feel they are partly responsible for the increased pricing and mobility challenges. Some have received undue attention because they are foreign. Meanwhile, a tense back-and-forth on social media between locals and IJGBs, arguing over who is worthy of attention and belonging, has ensued for more than a week – highlighting divisions between the communities.

In nearby Ghana, there are similar challenges due to an influx of diasporans through the country’s Year of Return programme that started in 2019 to mark the 400th anniversary of the arrival of African slaves in the US state of Virginia. Year of Return aimed to urge Black people abroad to travel back to Africa to tour, invest and even settle. In November, 524 members of the diaspora were made citizens.

The scheme has worked thanks to a relaxed visa procedure as tourists spend up to $2,589 each during the festivities, which contributes to efforts to shore up the economy. But this also means that the local population is affected due to soaring costs. Once Africa’s shining star, Ghana is grappling with an economic crisis that makes it difficult for many to indulge in detty December; many Ghanaians are now also considering emigration.

Sedinam Baku is one of the Ghanaians having a muted celebration this year due to the economy. Financial woes have made her conscious of not doing things in December that will make her suffer in the new year.

“It is usually me asking friends to go to certain places. It was very spontaneous in the previous year but now you have to know what the menu and price is like,” the 28-year-old public health worker told Al Jazeera. “Cocktails that used to cost 40 cedis [$2.70] now go for 96 cedis [$6.50] and food about three times its former price.”

This year, she is contemplating attending one concert and eating out only once. Besides, she says shows are recognisably smaller in outlook as organisers seek to downscale.

A stark reality

While detty December usually caters to the urban elite, the middle class and diaspora Nigerians, the strange outlook this year also points to a stark economic reality for those in the lower rungs of society, according to Adesuwa Giwa-Osagie, a historian and founder of Untold Stories, an online show spotlighting political and historical events.

“What is more frightening, what requires more urgency, is the [fate of the] urban poor and the rural poor. December was a time focused on giving and bounty. Unfortunately, even those who in previous years would share free bags of rice, plantain and chicken can no longer afford to do so. You have more people requiring charity and less people able to give,” she said.

“This means the imbalance in Nigerian society has become more glaring, the gap between the super-wealthy and the poor widening, as Nigeria’s middle class falls from striving to survival.”

Most Nigerians have seen their income erode due to inflation and currency devaluation and the average person spends more than 65 percent of their salary on food, according to the UN. Many cannot even afford to travel home for the holidays because fares have gone through the roof.

“This is the highest globally, and deeply concerning,” Gatefield’s Emoruwa said. “With soaring energy costs, whatever’s left of the disposable income is wiped out by transportation expenses. Nigerians have been reduced to the bare necessities. The simple joys of life, such as dining out or relaxing in a bar, have become luxuries few can afford.”

In Lagos, about eight of Bey’s IJGB friends are in the city this December and have been asking her to hang out with them. Even though she received a 10 percent raise to her monthly salary of 350,000 naira ($226) this year, she knows any socialising will leave a big dent in her finances.

On the other hand, she worries that not seeing friends will put a strain on her relationships. Some of her friends have offered to foot the bill when they go out.

“It obviously bothers me, but I don’t think there is anything I can do about it except to try and earn more next year,” Bey said. “But I still don’t know if earning more would help me. I don’t know how inflation is going to be next year. It has me feeling like I am in a box and [like] I don’t have a choice.”