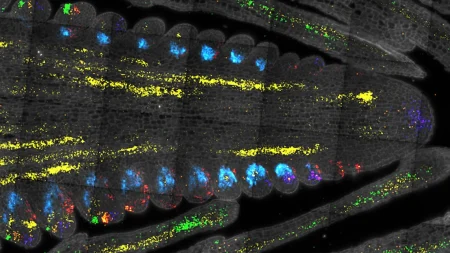

A team of researchers at the University of California San Diego has constructed the largest and most detailed bird family tree in history. This intricate chart outlines 93 million years of evolutionary relationships between 363 bird species, representing 92% of all bird families. By utilizing cutting-edge computational methods and the supercomputing resources at the San Diego Supercomputer Center, the team was able to analyze vast amounts of genomic data with high accuracy and speed, resulting in the most comprehensive bird family tree ever assembled. The updated tree provides insights into the evolutionary history of birds following the mass extinction event that wiped out the dinosaurs 66 million years ago. The researchers noted increases in effective population size, substitution rates, and relative brain size in early birds as a response to this pivotal event.

The research, detailed in two papers published in Nature and the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), sheds light on the adaptive mechanisms driving avian diversification following the catastrophe that led to the extinction of dinosaurs. By closely examining one branch of the newly constructed family tree, the team found that flamingos and doves are more distantly related than previous genome-wide analyses had suggested. This work is part of the Bird 10,000 Genomes (B10K) Project, which aims to generate draft genome sequences for approximately 10,500 extant bird species. The ultimate goal is to reconstruct the entire evolutionary history of all birds, providing crucial insights into avian biodiversity and evolution.

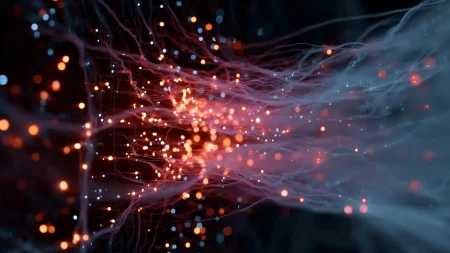

At the core of these studies are advanced computational algorithms known as ASTRAL, developed by Professor Siavash Mirarab’s lab, to infer evolutionary relationships with unprecedented scalability, accuracy, and speed. By integrating genomic data from over 60,000 regions, the team created a robust statistical foundation for their analyses. They examined the evolutionary history of individual segments across the genome, piecing together gene trees that were compiled into a comprehensive species tree. This meticulous approach enabled the construction of a detailed bird family tree, accurately delineating complex branching events with precision, even in cases of historical uncertainty.

The team’s ability to analyze massive datasets was facilitated by running their computations on powerful GPU machines and the Expanse supercomputer at the San Diego Supercomputer at UC San Diego. By employing a combination of genome sampling strategies, sequencing many genes from each species, and many species, the researchers maximized the accuracy of their tree reconstructions. This work has corrected past inaccuracies, revealing that an unchanged section of one chromosome skewed previous analyses and incorrectly grouped flamingos and doves as evolutionary cousins. By repeating their analysis with genomes from 363 species, the researchers produced a more accurate family tree, moving doves further from flamingos.

The impact of this research reaches beyond avian evolution, as the computational methods developed by Mirarab’s lab have become standard tools for reconstructing evolutionary trees across various animal species. Moving forward, the team plans to continue expanding the bird family tree by sequencing genomes of additional bird species to include thousands of bird genera. Computational scientists are refining their algorithms to accommodate even larger datasets, ensuring that future analyses are conducted with speed and accuracy. This groundbreaking work not only illuminates the evolutionary history of birds but also establishes a framework for understanding the biodiversity and evolution of various organisms.