ACL injuries are common in sports, with female athletes experiencing significantly more ACL injuries than their male counterparts. Previous research focused on biological factors such as anatomy and hormones, but ACL injury rates among girls and women have remained unchanged despite decades of research. Experts are now looking at how a gendered environment and sexism in sports may increase the risk of ACL injuries among female athletes and affect treatment outcomes.

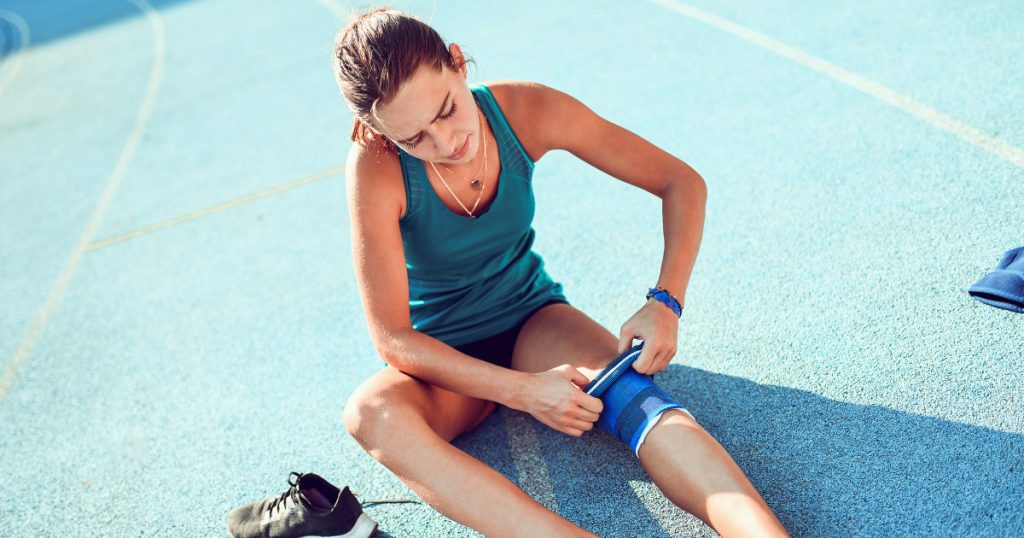

ACL injuries involve sprains or tears to the anterior cruciate ligament, a thick band of tissue in the knee that connects the thigh bone to the shin bone. These injuries often occur during agility-based sports that involve quick changes in direction or jumping and landing, such as soccer, basketball, and volleyball. ACL injuries can be season- or career-ending and have affected several high-profile athletes, including gymnast Rebeca Andrade, WNBA rookie Cameron Brink, and runner Courtney Frerichs.

In addition to playing certain sports, other risk factors for ACL injuries include poor conditioning or technique, faulty movements while landing, hyper-mobility, ill-fitting footwear, playing on artificial turf, and being female. Women have been found to have a higher risk of ACL injuries compared to men, with some studies suggesting a three to eight times higher risk for women. Despite years of research, the rate of ACL injuries among girls and women has not changed, while rates for boys and men have decreased slightly.

Research on gender disparities in ACL injuries has focused on biological factors such as anatomy, muscle strength, and hormone fluctuations. Women’s wider hips and pelvises, weaker muscles, and hormonal fluctuations during the menstrual cycle may contribute to a higher risk of ACL injuries. Additionally, environmental factors such as systemic gender inequality, bias, and sexism in sports may impact women’s risk of ACL injuries and their treatment outcomes. The lack of data and resources allocated to women’s sports also plays a role in ACL injury risk.

ACL injuries often require reconstructive surgery and rehabilitation, with recovery times ranging from several months to over a year. Women may not be offered surgery as often as men and may experience worse outcomes, including a higher risk of re-rupture. Gender disparities in treatment and recovery may be influenced by societal factors, such as caregiving responsibilities that affect women’s ability to focus on their own recovery. ACL injury prevention exercises, which focus on improving muscle strength and bodily control, may reduce the risk of ACL injuries and improve overall athletic performance for both men and women.

Overall, there is a need for more research to better understand the factors that contribute to ACL injury risk in female athletes. Addressing systemic issues such as gender inequality, bias, and lack of resources in sports may help reduce the risk of ACL injuries and improve treatment outcomes for female athletes. By considering a holistic approach that includes both biological and environmental factors, experts can work towards preventing ACL injuries and promoting the health and well-being of athletes of all genders.